Church schools. Monastery schools of the Middle Ages - the only affordable way of education Medieval schools types of educational process

DIDACTICS OF THE MIDDLE AGES

Historical and pedagogical characteristics of the early Middle Ages

The existence of a pedagogical tradition in the Middle Ages, as well as in other historical periods, the formation of pedagogical ideas, the implementation of the educational process are associated with the structural and functional structure of society, the type of social inheritance of the subjects of the educational process. The pedagogy of the Middle Ages has characteristic features, because, firstly, the pedagogical traditions of this era are not closed in time, they have their own historical past, well-established in their influences on modern Western European pedagogy. Secondly, a person of the Middle Ages defined himself not with ethnicity, but with a local one (village, city, family), as well as on a confessional basis, i.e. belonging to the ministers of the church or the laity. Both in the educational material and in the organization of special educational institutions there is a synthesis of reality with the new needs of society. The ideal of medieval education is the rejection of a comprehensively developed personality of the era of Antiquity, the formation of a Christian person. The new ideal of education defined the main European pedagogical tradition early medieval (V-X centuries) - the Christian tradition, which also determined the educational system of the era.

Types of educational institutions of the early Middle Ages

The beginning of Christian schools was laid by monasteries and associated with the school catechumens, where training and education were reduced to the study of Christian dogmas, leading to faith, preparation for the righteous search for "Christian birth" before baptism on Easter.

The main types of church schools were: parish, monastic, cathedral, or episcopal (cathedral). As such, there was no strict gradation in terms of the level of education of schools, but still there were some differences between them.

parochial school- this is an elementary (small) school, which was located at the church and gave basic knowledge to 3-10 students in the field of religion, church chanting, reading in Latin, and where counting and writing were sometimes taught. The only and main teachers were: the deacon or deacon, the scholastic or didascal, the magniscola, who were supposed to teach all the sciences. If the number of students increased, then the circulator specially observed the discipline.

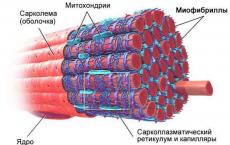

Monastic schools developed in close connection with episcopal schools that prepared successors for the diocesan clergy. The disciples gathered in circles around the bishop, receiving deep religious knowledge. So, the teaching rules of St. Benedict of Nursia (480-533) contained the requirement to read for three hours a day, and during fasting to read a whole book. The Benedictine school of the early Middle Ages is part of a whole complex of institutions with missionary tasks, where the problems of teaching secular sciences were also solved. The school was divided into schola claustri, or interior,- for monastic youth and schola canonica, or exterior,- for secular youth. The meaning of the old motto of the monks of the Benedictine order was that the fortress of the order, its salvation and glory are in its schools. The people who led education during this period belonged to this order. The educational activity of Albin Alcuin (735 - 804) went far beyond the scope of this era, since his monastic school in Tours was a "hotbed of teaching" until the 12th century. The abbey in Monte Cassino, where the center of the Benedictine order was located, is also famous for the fact that the outstanding theologian Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) later studied here. By the 16th century in the countries of Western Europe, there were about 37,000 monasteries belonging to the Benedictine order and orders descending from it (every fifth of them had a monastic school). In these schools the teachers were, as a rule, monks or priests who taught the children at fixed hours. The main subjects were the same as in parish schools, but later this circle expanded significantly, including rhetoric, religious philosophy, grammar, and, in some schools, quadrivium disciplines. In monastic schools, much attention was paid to copying books, due to which a library appeared in the monastery. The sages of that time said that a monastery without a library, that a fortress without protection.

From episcopal schools to the Middle Ages develop cathedral And cathedral school, in which there were also internal cenobitic schools for the younger generation - the clergy - and open ones (for the laity), the former having an educational character, and the latter educational. Schools of this type were considered elevated, since they were located in large church centers, where the full range of medieval sciences was taught - the “seven free sciences” (lat. septem artes liberales). In order to strengthen church authority and spiritual education, in 1215 the Council decided: to establish the position of teacher of grammar and theology at all cathedrals. Bishops were instructed to pay special attention to the education of youth, and bishops were to exercise control over all diocesan parish schools.

The order of the Council read: “Since the schools serve to prepare all those who will subsequently be in charge of secular and spiritual affairs in the state and the church, we command that in all cities and villages of our diocese the parish schools should be restored again where they are fell into decay, and where they still survived, developed more and more. To this end, parish priests, magisters, and respected members of society should see to it that the teachers, who are usually appointed kisters in the villages, are provided with the necessary maintenance. And the school should be organized in a suitable house near the parish church, so that, on the one hand, it would be easier for the pastor and noble parishioners to observe the teacher, and on the other hand, it would be more convenient to accustom students to religious exercises ... who settled in the parish under fear of a fine of 12 stamps were obliged to send their children to school, so that paganism, still smoldering in many hearts, would completely die out, ”and a report was to be submitted to the pastor every month on“ how the students succeed in Christian manners, writing and reading, and grow day by day in the fear of God, so that in the course of time they avoid evil and become more and more established in good. In theological schools in the Middle Ages, the laity were presented as both students and teachers, so this period does not distinguish between schools according to the direction of their educational activities. Lay teachers mainly introduced students to the seven liberal arts, Roman law, and medicine.

Christian educational institutions are characterized by the following features:

1) having a religious and moral ultimate goal, they were not only an educational type of institution, but also an educational one;

2) Christian education was combined with the teaching of writing, reading, singing;

3) due to their connection with the monasteries, the schools were not class-based, private, national and were of a public (mass) character.

In 313, when Christianity acquired the status of an official religion, the Christian communities were faced with the need to create church schools in order to spread the doctrine. In Europe of the early Christian period, there are almost no secular schools that have survived from late Antiquity. The church became the only center that contributed to the dissemination of knowledge, and the sacred teaching was the duty of the ministers of the church.

Naturally, the content of Christian education differed from secular and professional, knowledge had a pronounced religious orientation. Having become dominant, the church had to answer many questions in the field of education, including accepting or not accepting the pedagogical heritage of Antiquity.

In the period of the early Middle Ages, pedagogy rethinks the ancient heritage in education and introduces its own values - a guide to spiritual education, education by faith. Until the VI century. Christians received a grammatical and rhetorical education, the medieval pedagogical tradition inherited the language of ancient Rome from the previous era, and from the moment the Bible was translated into Latin, when church services began to be conducted in Latin, this language becomes common European and mandatory for learning. Of course, humanity could not reject the scientific achievements of the previous era, so the main dispute arose about the means and ways of comprehending secular knowledge by a Christian.

During the Middle Ages knowledge of human experience was carried out by giving it a divine manifestation, was based on the idea of the thinkers of this era that all existing reality in the world is distributed according to the degree of proximity to God. But there were others demarcation signs mastery of knowledge: according to the degree of divinity of knowledge; by the quality of the cognitive process (the need to include not only mental operations, but also physical activity, including in the form of fasting, obedience, etc.); according to the level of preparedness of the student and teacher for learning; on a corporate - social basis; by gender and age, etc.

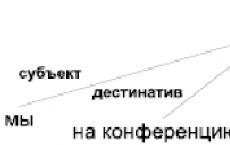

A characteristic feature of the content of education in the early Middle Ages was its emotional and symbolic character. With the help of the studied material, the teacher had to create a positive emotional mood of the process of cognition, so that the divine sphere of the student's soul was in tune with the divine meanings of the cognizable. Indicative in this case is the study of the Greek letter Y (upsilon), since this letter was a symbol of all human life. From birth to a conscious choice of a future path, a person moves from below in a straight line, and then follows the chosen path, where the left straight line is a wide and comfortable road of sin, and the right one, on the contrary, is a thorny path, the path of the righteous. In other words, the process of cognition was carried out in the whole complex of religious semantic meanings, symbols and allegories directed to the divine limits. An early medieval teacher told his student: "Wherever possible, combine faith with reason." From here purpose of education in the era of the early Middle Ages - the discipline of free will and reason and bringing a person with its help to faith, to comprehend and worship God and serve him.

Thus, the content of education had a dual focus: providing certain information and developing the spiritual intentions of the student. In the study of secular sciences, those useful things were selected that were created by God for the life of people or were piously invented by people themselves and that did not harm the main thing - education in the spirit of virtue and the fear of God. In the Middle Ages, the problem arises of choosing book or extra-book learning, the correlation of the role and significance of the word (reading, grammar, writing, etc.) with operational knowledge (craft, science, art, etc.), as well as ways to comprehend the incomprehensible to end of God. Thanks to verbal and book learning, the educational program of the theologian Aurelius Augustine (Blessed) (354 - 430), including the study of languages, rhetoric, dialectics, mathematics, there was an active development of church culture, an awareness of the need to assimilate church dogma by every Christian, i.e. The Western European pedagogical tradition defined the range of sciences, without which a person cannot develop and strengthen the Faith. First, a person had to master the basic skills of learning (reading, writing and counting), and then move on to comprehend the "seven liberal arts", the trivium of the verbal and quadrivium of mathematical sciences, as well as theology, theology and philosophy.

Education, as already noted, in the countries of Western Europe was conducted in Latin, there were no time frames for education. The only criterion for a student's transition to another level of education was the degree to which he mastered the material being studied.

The process of education began with memorization Psalter, because it was believed that the knowledge and repetition of psalms lead a person away from "unnecessary" vain thoughts, which was a necessary condition for the internal mood of children to comprehend the dogma, understanding the Bible.

Actually, the study of the "seven free arts" began with mastering latin grammar, which was considered the guide of the student to the world of sciences. The purpose of studying this art is to correctly read and understand the Holy Scriptures, to correctly express one's own thoughts.

Rhetoric and dialectic, on the one hand, they taught the child to compose and deliver sermons, and on the other hand, they formed the ability to think logically, argue convincingly and reasonedly, which also made it possible to avoid errors in dogma.

Mastering the highest level of education was given special importance due to the fact that this block of disciplines affirmed the dynamic perception of the “Divine Cosmos” based on the world of numbers by a person. When learning arithmetic four mathematical operations were mastered, and the interpretation of numbers was inextricably linked with the symbols of faith. So, the unit corresponded with the symbol of the one God, the two - with the symbol of the duality of Jesus Christ (Divine and human), the number three - this is the Holy Trinity, etc. Geometry supplemented its content with the 7 course of arithmetic, since it was considered as a science about the structure of the world around with the help of numbers. They also sought a philosophical basis in music, believing that it brings the heavenly and earthly spheres into harmony. Astronomy was considered as a science, also in the service of the church, since it was engaged in the calculation and calculation of church holidays, fasts.

In cathedral schools, the crowning achievement of education was the comprehension philosophy, which completed the course of the "seven free arts" and led to the comprehension of theology, mastery of the wisdom of symbolic analogies, comprehension of the picture of the world.

Considering pedagogical process in the era of the early Middle Ages, it is necessary to highlight its main trends and characteristic features:

1. The main way of learning is apprenticeship. The pedagogical tradition of mentorship in religious education manifested itself in the form of apprenticeship of a monk, a clergyman with God; in secular education (knightly, craft), the child was a student of the master. The main form of work with the student was individual work on the transfer of knowledge and instructions.

2. The high role of verbal and book learning. The structure of the content of education, its orientation are connected with the comprehension of two worlds by a person: heavenly and earthly. This mutual influence is expressed in the fact that, comprehending the real world, mastering the sciences of the earth, a person moves to the Highest wisdom, where there is the harmony of music, the arithmetic of heaven and the grammar of the Bible. But the whole world was created by the Divine Word, which is embodied in the holy book - the Bible. Learning helps to master the Truth of the Word. Logical and grammatical education was one of the tasks of education, hence the verbal (catechetical - question-and-answer) teaching method as the main one, i.e. verbal teaching, or learning the Word.

3.Development of the student's memory since any kind of distortion of the Sacred Text, quoted treatises of the Fathers of the Church, canons, theological writings were unacceptable. The universal teaching method was the memorization of samples and their reproduction. Already in early Christian pedagogy, it was proposed to use the mechanisms of associative memory, correlating the content of the text with its location, pattern, place of memorization, etc. Memory served the student as a library.

4. The basic principle of education is authoritarianism. To a greater extent, severity, punishments were used to educate a Christian person in the "fear of God", which will ensure, firstly, the development of Reason and Faith, and secondly, the ascent to the comprehension of Truth and Wisdom. The fear of God and love are considered by the Fathers of the Church in interconnection, since a disciplined will through Fear destroys pride that interferes with the reverence of the Lord: “Teach not rage, not cruelty, not anger, but joyfully visible fear and loving custom, sweet teaching and affectionate reasoning.”

5. The main means of teaching and educating a child is the family world. The foundations for the development of the child were laid in the family, which was a visual aid for labor education, the formation of religious beliefs, and for initial socialization.

6. The interaction of teacher and student in the learning process was based on the understanding that the main teacher is God. At the same time, both the student and the teacher were aware of this fact, so the Divine principle was considered the main source of education.

7. Didactic instruction in the comprehension of the Divine Mysteries. This applied to any science studied. The universality of knowledge consisted in the fact that it was necessary to comprehend the contradiction that arises between the Divine unity of the world and the diversity of the surrounding reality. This was the phenomenon of the need to acquire encyclopedic knowledge.

8.Inclusion in the educational process of visibility. Teaching reading was carried out by a difficult letter-subjunctive method. They learned to read from the abetsedary - a manual resembling a primer. Students of this stage of education were also called abetsedarii. The sounds of speech, deposited in the children's memory, were depicted, which helped the students to connect the sound and the letter. The main aids in teaching grammar were the treatises of the thinkers of early Christianity, Antiquity, as well as the textbook by Donat Alcuin, from which the teacher read the texts, and the students, writing them on the tablets, memorized and retold. It is known that students started dictionaries, where there was a translation from Latin, and also visual material was used in the form of an image of a person, on whose body parts verbs were inscribed.

The progress of the development of society has always been associated with the knowledge of science and education. The impetus for this development was given by the Middle Ages. It was then that a huge contribution was made to the development of schools.

In the pedagogy of the Middle Ages, there was an element of authoritarian personality. Many openly showed hostility to an upbringing that included Greek and Roman literature. It was believed that the model of education is monasticism, which began to spread in the Middle Ages.

Medieval monastic school

The very first institutions where one could study were monastic schools. Despite the fact that the church left the sciences that she needed, it was from them that the cultural tradition began, which connected different eras.

As the culture of the population developed, the first universities began to appear. They had a legal, financial and administrative focus. By 1500 there were already 80 universities.

Medieval monastic schools were divided into external and internal. They gave a deeper education. The advantage was that the school had access to the library. Many people who were educated were monks.

Schools that belonged to the internal type were intended only for monks or those who were preparing to become monks. To do this, it was necessary to obtain special permission from the abbot of the monastery. Those schools that were called external accepted strangers.

There were also schools that prepared future clergy. The level of training and education of such schools was minimal.

The monastic schools could only be attended by boys. There was practically no pedagogy of education, instead of it there were thoughts about religious education, which were contained in the literature.

Education was broader in internal schools. Teachers demanded that students read Latin prose and verse as a greeting. If there was a desire, some could take individual lessons. Particular attention was paid to writings in Latin. From the Greek language, only the alphabet and individual words from the liturgy were taken.

With each lesson, knowledge increased. The monastery had workshops for correspondence. Manuscripts were copied, which were taken out of Italy, and then distributed throughout Europe.

The abbots were engaged in collecting books for the monastery, urging them to read exactly the original texts. Soon the monastic schools began to expand into other sciences, such as music, medicine, and mathematics. Wandering students appear, which has become one of the sources of vaganism.

And yet, the most important concern of the monastery was the compilation, and then the census of texts to the Holy Scriptures.

What was taught in a medieval monastic school?

In the Middle Ages, there were three types of schools, these are parochial, monastic and cathedral schools.

For the lower strata of the population there were separate systems of education. They studied counting, rhetoric, reading and writing. For the feudal lords, a system of knightly education was adopted, where they taught horseback riding, swimming, fencing, possession of a spear and playing chess. The main book was the Psalter. Antique and Christian tradition intertwined in practice and teaching.

Schools prepared almost the same priests. If education was paid, then it was taught only in Latin. Such training was supposed for wealthy citizens. The study began with the study of prayers, then there was an acquaintance with the alphabet and reading the same prayers from the book.

When reading, words and expressions were memorized, no one delved into the meaning. That is why, not everyone who could read Latin texts could understand what they read.

Above all subjects was grammar. It took about three years to learn to write. On a special board, which was covered with wax, the students could practice writing, and only then they took up the pen and could write on parchment. The numbers were depicted with the help of fingers, they learned the multiplication table, learned to sing and got acquainted with the dogma.

Many students were reluctant to memorize and Latin, leaving school half literate and able to read the texts of books a little.

Some large schools gave more serious knowledge and were appointed at episcopal sees. They studied literacy, arithmetic numbers, rhetorical, dialectical and geometric sciences. Additional subjects were music and astronomy.

Art included two levels. The initial level consisted of teaching literacy, rhetoric and dialectics. And the highest included all the other arts. Grammar was considered the most difficult. She was represented as a queen with a bug-cleaning knife in one hand and a whip in the other.

The students also practiced conjugation and declension. In rhetoric, they taught the rules of syntax, stylistics, composed letters, letters and business papers.

Dialectics was of particular importance, it taught not only to reason and draw the right conclusions, but also to find an opponent of the teachings of the church. Arithmetic taught addition and subtraction. The students solved various problems, learned to calculate the time of religious holidays. Even in numbers they saw a special religious meaning. Next to arithmetic was geometry. All tasks were general, without evidence. Particular attention was paid to geographical information in this science. In astronomy, they got acquainted with the constellations, the movement of the planets, but the explanation was not accurate.

There was a harsh atmosphere in the monastery school. Teachers did not feel sorry for the students for mistakes, corporal punishment was used, which the church approved.

During this period, all people who were literate belonged to the same class and studied in schools that were created by representatives of these classes.

The European Middle Ages borrowed the system of school education from antiquity, but enriched it and adapted it to new conditions.

In the Middle Ages, both church (at monasteries and city cathedrals) and secular schools were opened. Children of feudal lords, townspeople, clergy, wealthy peasants studied there. The “seven liberal arts” were taught in schools: grammar (it was considered the mother of all sciences), rhetoric (eloquence), dialectics (the so-called logic), arithmetic, geometry, astronomy (the science of the structure of the universe) and music. Until the end of the Middle Ages, teaching was carried out in Latin, and only from the XIV century. - vernacular languages.

| Lesson. Miniature of the 14th century. |

At school, both children and adults studied in the same class. Children at school were treated with all severity: they were forbidden to speak loudly, sing, play, they were punished for any misconduct. Schoolchildren themselves got a piece of bread. They worked part-time, but more often they asked for alms. At night they sang religious songs under the windows of the townspeople. More precisely, they didn’t sing, but yelled at the top of their lungs in order to “instantly raise a respectable burgher from the bed and force him to hastily pay off the terrible melody with a piece of sausage or cheese thrown through the window.”

In the XIII century. schools in the largest cities have become institutions of higher education - universities ("aggregate", "community"). The first European university arose in the Italian town of Bologna (it became a recognized center of legal science). The university in the Italian city of Salerno became the center of medical knowledge, in the French city of Paris - the center of theology. In 1500, there were already about 70 such centers of knowledge and culture in Europe. In the XIV-XV centuries. in European countries, especially in England, also appeared colleges(hence the colleges).

Teaching in medieval universities was carried out as follows. The professor (“teacher”) read a handwritten tome in Latin, explaining difficult places in the text. The students were sleeping peacefully. There was little use for such teaching, but before the invention in the middle of the 15th century. typography could not organize teaching in a different way, since there were not enough handwritten books and they were very expensive. Printed books have become an accessible source of knowledge and have revolutionized the education system. material from the site

|

| The oldest universities in Europe |

Until the 12th century books were kept mainly in small monastic libraries. They were so rare and expensive that they were sometimes chained. Later, universities, royal courts, large feudal lords, even wealthy citizens also acquired them. In the XV century. public libraries appeared in big cities.

Dispute - oral scientific dispute.

Boards - closed secondary or higher educational institutions.

University - a higher educational institution that trains specialists in many fields of knowledge and is engaged in scientific work.

Didn't find what you were looking for? Use the search

A small room with a low vaulted ceiling. Rare rays of sunlight make their way through the narrow windows. Boys of different ages sit at a long table. Good clothes betray the children of wealthy parents - there are clearly no poor people here. At the head of the table is a priest. In front of him is a large handwritten book, nearby lies a bunch of rods. The priest mutters prayers in Latin. Children mechanically repeat incomprehensible words after him. There is a lesson in a medieval church school ...

The early Middle Ages are sometimes referred to as the "Dark Ages". The transition from antiquity to the Middle Ages was accompanied in Western Europe by a deep decline in culture.

Not only the barbarian invasions that finished off the Western Roman Empire led to the destruction of the cultural values of antiquity. No less destructive than the blows of the Visigoths, Vandals and Lombards, was the hostile attitude of the church for the ancient cultural heritage. Pope Gregory I waged an open war against ancient culture. He forbade the reading of books by ancient authors and the study of mathematics, accusing the latter of having links with magic. The most important area of culture, education, was going through particularly difficult times. Gregory I once proclaimed: "Ignorance is the mother of true piety." Truly ignorance reigned in Western Europe in the 5th-10th centuries. It was almost impossible to find literate people not only among the peasants, but also among the nobility. Many knights put a cross instead of a signature. Until the end of his life, he could not learn to write the founder of the Frankish state, the famous Charlemagne. But the emperor was clearly not indifferent to knowledge. Already in adulthood, he resorted to the services of teachers. Having begun to study the art of writing shortly before his death, Karl carefully kept waxed boards and sheets of parchment under his pillow and learned to draw letters in his spare time. In addition, the sovereign patronized scientists. His court in Aachen became the center of education. In a specially created school, the famous scientist and writer, a native of Britain, Alcuin taught the basics of science to the sons of Charles himself and the children of his entourage. A few educated people came to Aachen from all over illiterate Europe. Following the example of antiquity, the society of scientists who gathered at the court of Charlemagne began to be called the Academy. In the last years of his life, Alcuin became the abbot of the richest monastery of St. Martin in the city of Tours, where he also founded a school, whose students later became famous teachers of the monastery and church schools in France.

The cultural upsurge that occurred during the reign of Charlemagne and his successors (the Carolingians) was called the "Carolingian Renaissance". But he was short-lived. Soon cultural life again concentrated in the monasteries.

Monastic and church schools were the very first educational institutions of the Middle Ages. And although the Christian Church retained only selective remnants of ancient education it needed (first of all, Latin), it was in them that the cultural tradition continued, linking different eras.

The lower church schools prepared mainly parish priests. Paid education was conducted in Latin. The school was attended by children of feudal lords, wealthy citizens, wealthy peasants. The study began with the cramming of prayers and psalms (religious chants). Then the students were introduced to the Latin alphabet and taught to read the same prayers from the book. Often this book was the only one in the school (manuscript books were very expensive, and it was still far from the invention of printing). When reading, boys (girls were not taken to school) memorized the most common words and expressions, without delving into their meaning. No wonder that not everyone who learned to read Latin texts, far from colloquial speech, could understand what they read. But all this wisdom was hammered into the minds of the disciples with the help of a rod.

It took about three years to learn to write. The students first practiced on a waxed board, and then learned to write with a goose quill on parchment (specially treated leather). In addition to reading and writing, they learned to represent numbers with their fingers, memorized the multiplication table, trained in church singing and, of course, got acquainted with the basics of Catholic doctrine. Despite this, many pupils of the school were forever imbued with aversion to cramming, to Latin alien to them, and left the school walls semi-literate, able to somehow read the texts of liturgical books.

Larger schools, which provided a more serious education, usually arose at episcopal sees. In them, according to the preserved Roman tradition, they studied the so-called "seven liberal arts" (grammar, rhetoric, dialectics, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music). The liberal arts system included two levels. The initial one consisted of grammar, rhetoric, dialectics. Higher formed all the remaining free arts. The hardest part was grammar. In those days, she was often depicted as a queen with a knife for erasing errors in her right hand and with a whip in her left. Children memorized definitions, practiced conjugation and declension. A curious interpretation was given to letters: vowels are souls, and consonants are like bodies; the body is motionless without the soul, and consonants without vowels have no meaning. In rhetoric (the art of eloquence), the rules of syntax, stylistics were passed, they practiced in compiling written and oral sermons, letters, letters, business papers. Dialectics (as the art of thinking was then called, later called logic) taught not only to reason and draw conclusions, but also to find in the opponent’s speech provisions that contradict the teachings of the church, and refute them. Arithmetic lessons introduced addition and subtraction, to a lesser extent - multiplication and division (writing numbers in Roman numerals made them very difficult). Schoolchildren solved arithmetic problems, calculating the time of religious holidays and the age of the saints. They saw a religious meaning in the numbers. It was believed that the number "3" symbolizes the Holy Trinity, and "7" - the creation of the world by God in seven days. Geometry followed arithmetic. She gave only answers to general questions (what is a square? Etc.) without any evidence. Geographic information was also communicated in the course of geometry, often fantastic and absurd (Earth is a pancake floating in water, Jerusalem is the navel of the earth ... etc.). Then they studied astronomy. They got acquainted with the constellations, observed the movement of the planets, the Sun, the Moon, the stars, but they explained it incorrectly. It was thought that the luminaries revolve around the Earth along various complex paths. Astronomy was supposed to help calculate the timing of the onset of church holidays. Studying music, the students sang in the church choir. Education often stretched for 12-13 years.

From the 11th century the number of church schools grew. A little later, the rapid development of cities leads to the emergence of secular urban private and municipal (i.e., run by the city council) schools. The influence of the church was not so strong in them. Practical needs came to the fore. In Germany, for example, the first burgher schools, preparing for crafts and trade, arose: in Lübeck in 1262, in Wismar in 1279, in Hamburg in 1281. From the XIV century. some schools teach in national languages.

Growing cities and growing states needed more and more educated people. Judges and officials, doctors and teachers were needed. The nobility was increasingly involved in education. According to the description of the English medieval poet Chaucer, a nobleman of the XIV century - "Fairly knew how to compose songs, He knew how to read, draw, write, Fight on spears, deftly dance."

The time has come for the formation of higher schools - universities. They arose either on the basis of former cathedral (episcopal) schools (this is how the University of Paris appeared in the 12th century, which grew out of the school that existed at the Notre Dame Cathedral), or in cities where illustrious teachers lived, always surrounded by capable students. Thus, from the circle of followers of the famous expert on Roman law, Irnerius, the University of Bologna, the center of legal science, developed.

Classes were conducted in Latin, so the Germans, French, Spaniards could listen to the Italian professor with no less success than his compatriots. Students also communicated in Latin with each other. However, in everyday life, "strangers" entered into communication with local bakers, brewers, tavern owners and landlords. The latter did not know Latin and were not averse to cheating and deceiving a foreign scholar. Since the students could not count on the help of the city court in numerous conflicts with local residents, they, together with the teachers, united in a union, which was called the "university" (in Latin - community, corporation). The University of Paris included about 7 thousand teachers and students, and in addition to them, booksellers, copyists of manuscripts, manufacturers of parchment, pens, ink powder, pharmacists, etc. were members of the union. teachers and schoolchildren left the hated city and moved to another place), universities achieved self-government: they had elected leaders and their own court. The University of Paris was granted independence from secular authorities in 1200 by a charter from King Philip II Augustus.

The life of schoolchildren from poor families was not easy. Here is how Chaucer describes it:

Having interrupted hard work on logic,

An Oxford student trudged along with us.

Hardly a poorer beggar could be found ...

I learned to endure Need and hunger steadfastly,

He put the log at the head of the bed.

He is sweeter to have twenty books,

Than an expensive dress, a lute, food ...

But the students were not discouraged. They knew how to enjoy life, their youth, to have fun from the heart. This is especially true for vagants - wandering schoolchildren moving from city to city in search of knowledgeable teachers or an opportunity to earn extra money. Often they did not want to bother with their studies, they sang with pleasure the vagants at their feasts:

Let's drop all wisdom, side teaching!

To enjoy in youth is Our purpose.

University teachers created associations in subjects - faculties. They were headed by deans. Teachers and students elected the rector - the head of the university. Medieval high school usually had three faculties: law, philosophy (theology) and medicine. But if the preparation of a future lawyer or physician took 5-6 years, then the future philosopher-theologian - as many as 15. But before entering one of the three main faculties, the student had to complete the preparatory - artistic faculty (the already mentioned " seven free arts"; "artis" in Latin - "art"). In the classroom, students listened to and recorded lectures (in Latin - "reading") of professors and masters. The teacher's erudition was manifested in his ability to explain what he read, to connect it with the content of other books, to reveal the meaning of terms and the essence of scientific concepts. In addition to lectures, debates were held - disputes on issues raised in advance. Hot in heat, sometimes they turned into hand-to-hand fights between the participants.

In the XIV-XV centuries. so-called colleges appear (hence - colleges). At first, this was the name of the student hostels. Over time, they also began to hold lectures and debates. The collegium founded by Robert de Sorbon, the confessor of the French king, the Sorbonne, gradually grew and gave its name to the entire University of Paris. The latter was the largest higher school of the Middle Ages. At the beginning of the XV century. in Europe, students attended 65 universities, and at the end of the century - already 79. The most famous were Paris, Bologna, Cambridge, Oxford, Prague, Krakow. Many of them exist to this day, deservedly proud of their rich history and carefully preserving ancient traditions.