Chapter I. Age characteristics of school-age children. Primary school age and its features Primary school age and its features

Primary school age is a period of absorption, assimilation, and accumulation of knowledge. This is favored by trusting submission to the authority of an adult, increased receptivity, attentiveness, and a naive and playful attitude to reality. Age is receptive and impressionable, everything new causes an immediate reaction. Increased reactivity and readiness for action may be accompanied by impatience and readiness to respond.

Children have a very strong focus on the outside world: they remember facts and phenomena in detail, for a long time they are in the power of a vivid fact and image, their experiences are vivid and immediate. At the same time, seven-year-olds do not show any desire to penetrate into the depths of a phenomenon, to establish its cause and connections with other phenomena. An important mechanism for the personal development of younger schoolchildren is imitation - they literally copy the manners, actions, and reasoning of the teacher. This feature obliges primary school teachers to be responsible for their behavior. An important age-related feature associated with the beginning of educational activity is a socially mediated attitude to reality, a departure from being bound by a specific situation or “loss of spontaneity.”

A.V. Monrose identifies the main patterns of age-related changes in the structure of volitional qualities:

The movement is moving towards more complexity and greater differentiation of the connections of volitional qualities, as well as a decrease in the orthogonality of the connections of properties. At the same time, for first-grade students, this structure consists of a workshop of two groups of qualities, and only in the process of growing up does a third one emerge;

Significant qualitative changes begin to occur in children aged 8-9 years; this is manifested in the emergence of a connecting group of qualities, in many ways similar to the moral-volitional regulation of adults. This group of properties becomes increasingly important and arbitrary by the age of 10-11.

Thus, the ability to master one’s own behavior – self-control – initially develops. Then the development of motivational-volitional regulation - self-determination (class I) becomes more important. Only lastly is the ability to build one’s behavior in accordance with moral rules and norms formed.

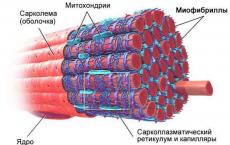

Physiological changes in primary school age are significant, but development occurs smoothly and gradually.

All the curves of the spine are being formed, but ossification has not yet been completed, which makes the children's spine vulnerable to deformations, hence the requirements for seating, furniture, and ensuring mandatory physical activity (at least half of the time the child is in school must be in motion).

Ligaments and muscles (especially large ones) become stronger, while small muscles lag behind in development. In seven-year-old children, due to the poor development of the small muscles of the hand, it may quickly become tired, and this can lead to hand tremors and “trembling” lines when writing. This fact requires adherence to a writing regime: the duration of writing for first-graders should not exceed five minutes, followed by rest and exercise for the hand. Ossification of the phalanges of the fingers is completed by nine to ten years, and of the wrist by ten to eleven years.

The heart muscle grows rapidly. The heart becomes more resilient to stress. The blood supply to the brain is intense; it increases in mass, approaching adult size. The frontal lobes are especially enlarged. The relationship between excitation and inhibition changes in favor of the latter, but excitability is still high.

By the age of seven, myelination of nerve fibers ends, which increases the resistance of the nervous system and the protective capabilities of the body as a whole: even resistance to colds and infectious diseases increases.

At the age of six to ten to eleven years, pronounced unilateral dominance of the hand and all symmetrical parts of the body endowed with autonomous motor function is established. It has been established that the vast majority of children become right-handed; left-handed people are less common. But if practice indicates clear left-handedness, the child should write with his dominant hand.

In general, by the age of seven, physiological readiness for learning is noted.

Intensive sensory development in preschool age provides a level of perception sufficient for learning - high visual acuity, hearing, orientation to the shape and color of an object. However, the characteristics of children's perception remain syncretism, as well as high emotionality. Syncretism manifests itself in the perception of phenomena and situations as undifferentiated; the perception of “blocks”, characteristic of a preschooler, persists into primary school age. This feature makes it difficult to perform analysis operations necessary in educational activities. It is difficult for children to highlight the main thing and differentiate the differences between objects and phenomena. An illustration of this feature of children's perception is the “mirror writing” of first-graders - young students confuse letters and numbers of similar configurations (for example, 9 and 6).

IN AND. Eidlin notes that the perception of works of art is studied, as a rule, through the analysis of their retelling and subsequent conversation about the content of what was read. It has been established that it is extremely difficult for children to convey the text of these works in their own words. When transmitting a text, children are most often only able to quote its fragments that they accidentally learned. These fragments can often be quite significant in volume. Errors that can be detected when reproducing text are associated with the loss of a particular word or fragment of text from memory; they are not the result of insufficient or erroneous understanding of it.

High emotionality of perception is manifested in the fact that children primarily react to vivid phenomena and details that evoke an emotional response in them (albeit secondary ones). For this reason, they are easily distracted. Therefore, the teacher should be very careful in selecting illustrative visual material and strive to prevent extraneous stimuli from being involved in the teaching process. In general, the perception mechanism is ready, but children do not know how to use it. Learning requires the development of arbitrariness and meaningfulness of perception, orientation towards a standard.

At the beginning of learning, children's attention is involuntary. The development of voluntary attention is facilitated by a clear organization of the child’s actions using a model, as well as self-control actions: this can be checking one’s own or others’ mistakes, comparing the result obtained with the correct one, etc.

The volume and distribution of attention remain low, for this reason it is difficult for primary schoolchildren to perform two actions at the same time (listening and writing, as when writing dictations), and the stability of attention remains low. Moreover, stability is higher when performing objective actions and lower when performing actions in the internal plan. If the stability of attention in first-graders is characterized by the ability to hold it on an object for no more than 10 minutes, then by the third grade this time increases to 20 minutes. In the process of educational work, involuntary attention also develops, and it is already associated with the needs and interests of the child, and not just with the characteristics of the stimuli that attract attention. The teacher should work on the development of post-voluntary attention and rely on it in educational activities, as a more gentle type of attention, in order to relieve unnecessary tension in educational activities.

L.V. Cheremoshkina emphasizes that primary school age, as is known, is sensitive for the formation of learning skills, for mastering the content, means and methods of action and the forms of cooperation corresponding to this action. The development of memory at this age is extremely intensive, since educational activities require the child to assimilate a large amount of information. Mnemonic abilities as an instrumental (instrumental) basis of memory are manifested in the process of implementing any cognitive activity, they are expressed in the productivity and qualitative originality of different types of memory and are stereotyped mental processes aimed at remembering, preserving and reproducing information.

Educational activity as the leading type of activity at primary school age creates fundamentally new conditions for the development of a child’s memory. It not only trains functional mechanisms and develops operational ones, but also forms ways to regulate the process of memorization and reproduction.

At primary school age, children do not yet master rational memorization techniques. Even by the third grade, only ten percent of students are proficient in voluntary mnemonic activity, another ten percent can independently identify a mnemonic problem, but do not know how to solve it, eighty percent cannot identify a mnemonic problem, much less solve it. With age, mnemonic activity becomes more voluntary and meaningful. By the third grade, the productivity of voluntary memory is higher than that of involuntary memory. Subsequently, both types of memory develop interconnectedly.

By improving the third class of thinking operations, the possibility of more logical and coherent reproduction becomes possible.

Voluntary memory becomes a function on which educational activity is based, and the child comes to understand the need to make his memory work for himself.

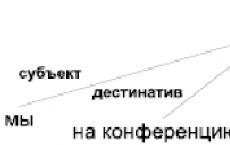

At the beginning of schooling, the child’s thinking is characterized by egocentrism, a special mental position - “centering” or perception of the world of things and their properties from the only position possible for the child. The thinking of younger schoolchildren is visual-figurative in type, and inductive in logic. The mental operations of younger schoolchildren differ in a number of features. Thus, the comparison operation for first-graders is replaced by juxtaposition, i.e., a sequential listing of the characteristics of the objects being compared. Comparison is carried out first according to the features of difference, then - according to the features of similarity of objects and phenomena. Generalization takes place according to the type of generalization - based on insignificant characteristics of objects. Abstraction is carried out on the basis of external, bright signs.

In the process of learning activities, children receive a lot of descriptive information. This requires them to constantly recreate images, without which it is difficult to understand the educational material. Thus, imagination is included in educational activities, performing a gnostic function. The “building material” for it are ideas (images of memory). At first, the imagination of younger schoolchildren is characterized by a slight processing of existing ideas. A characteristic feature when creating imaginative images is the reliance on specific objects, which is replaced by reliance on the word; later, reliance on the internal plane, thought, appears. The images themselves change from sketchy to full, bright, expanded - they include more features. According to J. Piaget, imagination undergoes a genesis similar to that of intellectual operations: at first it is static, limited to the internal reproduction of states accessible to perception; As the child develops, the imagination becomes more flexible and mobile, capable of anticipation and transformation.

The level of children's imagination depends on the work of the teacher in accumulating a system of thematic ideas in them.

Starting school can be a crisis. The seven-year crisis is characterized by transformations in the child’s psyche associated with changes in the child’s real situation, and largely depends on his individual development.

A child’s arrival at school is associated with a restructuring of all systems of his relationships with the outside world. The leading activity of a primary school student is academic. A distinctive feature of a student is that his studies are a mandatory, socially significant activity. The life of a student is subject to a system of strict rules that are the same for all students. Its main content is the acquisition of knowledge. By mastering the skills of writing, counting, reading, etc., the child orients himself towards self-change - he masters the necessary methods of official and mental action inherent in the culture around him. Reflecting, he compares his former self and his present self. Own change is traced and revealed at the level of achievements.

A.N. Poddyakov notes that higher rates of creativity and intelligence are demonstrated by those children who actively participate in the cultural and leisure activities of the school.

According to D.B. Elkonin, educational activity includes a learning task, learning actions, control action, evaluation action. At primary school age, each of its structural elements has a number of specific features. An educational task is often set by a teacher and accepted by a schoolchild; learning activities are also organized by an adult and are of a general nature for a group of children. The control function is the absolute privilege of the teacher; children carry it out as an action according to a model. Every educational activity begins with the child being assessed. Through assessment, one identifies oneself as the subject of changes in educational activities. Educational activities develop in children the ability to subordinate their work to rules that are mandatory for everyone, and the ability to regulate their behavior. Effective formation of educational activities depends on the content of the material being learned, specific teaching methods and forms of organizing schoolchildren’s educational work. A necessary condition for the developmental impact of educational activities on primary schoolchildren is the motivation to achieve success: only this motivation contributes to the development of cognitive activity, the manifestation of initiative, independence, and the removal of personal anxiety. According to L.I. Bozhovich, who studied the role of educational activities for the development of mental processes and the personality of a junior schoolchild, interaction in an organized school team leads to the development of complex social feelings in the child and to practical mastery of the most important norms and rules of social behavior. In this activity, both the child’s logical thinking and the higher forms of his perception and memory develop. At primary school age, intellectual development is especially important. Intelligence mediates the development of all other functions, the intellectualization of all mental processes, their awareness and arbitrariness occurs.

Conclusions on the first chapter

The development of morality in the process of personality formation is a complex and individual process. Questions about the decisive role of moral education in the development and formation of personality have been recognized and raised in pedagogy since ancient times. According to Ya.A. Comenius, the goal of a single process of spiritual and moral education is to establish a connection between the rules of life and the laws of eternity. The outstanding Swiss democratic teacher G. Pestalozzi assigned the same large role to moral education. He considered moral education to be the main task of a children's educational institution. However, of the classic teachers of the past, K.D. most fully and vividly characterized the role of moral education in the development of personality. Ushinsky.

In the modern period, a legal society is being created with a high culture of relations between people, which will be determined by social justice, conscience and discipline. The development of morality and spirituality in the process of personality formation is a complex and individual process. It largely depends on the external influence exerted on the child by family, school, church and society as a whole. In practical terms, spiritual and moral education is, on the one hand, the formation of positive values and the ability to reflect on various negative influences of the environment and resist them. The formation of morality, or moral education, is nothing more than the translation of moral norms, rules and requirements into knowledge, skills and habits of behavior of the individual and their strict observance.

One of the key factors in the modernization of the country in accordance with the national educational initiative “Our New School” is spiritual and moral education, defined by the second generation Federal State Educational Standard as a national priority. In the context of the most important national task and on the basis of the national educational ideal, the goal of modern education is formulated; one of the priority tasks of society and the state is to educate a spiritual, moral, responsible, proactive and competent citizen of Russia; the results of spiritual and moral education should be directly related to the areas of personal development and presented in activity form. In accordance with the requirements of the Federal State Educational Standard of the second generation, currently in the field of moral education, the task of the school is to ensure that, in the process of self-determination, the younger student, based on the correlation of his value system with universal value systems, makes an informed choice and forms a stable and consistent system of value orientations that can ensure self-regulation and self-determination of the individual, harmonization of its relationships with the world and with itself.

Primary school age is a period of absorption, assimilation, and accumulation of knowledge. The leading activity of a junior schoolchild is academic, but at the same time, at this age, play as an activity is of no small importance. In the process of educational activities, the development of mental processes and the personality of a junior schoolchild, interaction in an organized school team, the child develops complex social feelings and ensures practical mastery of the most important norms and rules of social behavior.

Junior schoolboy

J. Korczak persistently emphasized the intrinsic value of childhood as a genuine, and not a preliminary stage of a future “real” life. In his opinion, childhood is the foundation of life: without a full, fulfilling childhood, subsequent life will be flawed.Each age period has its own special value, its own development potential, its own significance ensuring the transition to the next age stage.

The family is for a child not only the source and condition for the development of his psyche, the expansion of his knowledge and ideas about the world around him, but also as the first model of social relations accepted in a given society that he encounters.

It is in the family that the child becomes acquainted with the meaning and essence of the social roles of mother, father, grandmother, grandfather, brother, sister, son, daughter.

The social development of a child begins in the first weeks and months of his life. The helplessness of a newborn is an unconditional prerequisite for his turning towards the people around him. A child’s well-being in subsequent years, including school years, largely depends on how successful his early social experiences turned out to be.

The older a child becomes, the greater the role that aspect of his social development begins to play: mastery of the norms and rules of social relationships. It is not enough to simply provide a child with knowledge of how human society works and how it is customary to behave in it. It is necessary to create conditions for him to acquirepersonal social experience, since socialization presupposes the active participation of the person himself in mastering the culture of human relations, mastering social norms and roles, and developing psychological mechanisms of social behavior.

Preschool age is a period of active learningsocial norms.

The first any serious demands on a child in terms of mastering social norms are made precisely at school, so parents and educators do not set themselves the task of social development of a preschooler; it firmly occupies a secondary place in their minds. Priority is given to mental development, training, preparation for school, and socialization occurs spontaneously, as if by itself and itsquality rarely becomes the subject of parental attention and concern. Meanwhile, it is in the preschool years that the first stereotypes of social behavior take shape and an individual’s individual style of behavior is formed.

Undersocialization It is customary to understand the entire multifaceted process of a person’s assimilation of the experience of social life and social relations. In the course of socialization, a person becomes familiar with the norms and rules of the social order, masters the meaning of different social roles, and acquires a certain level of cultural knowledge and skills. As a result, a person acquires qualities, values, beliefs, and socially approved forms of behavior, without which normal life in society is impossible.

Meanwhile, the concept of socialization does not replace or replace the concepts of training and education.

Socialization is a very long process; the expansion and generalization of social experience occurs throughout a person’s life. However, it begins very early, simultaneously with the moment when the child is physically separated from the mother.

The entire history of a child’s development is a chain of successive breaks.: birth, weaning, walking independently, entering a nursery or kindergarten, then school, etc. The more independent a child becomes, the more opportunities he has for acquisition of personal social experience, and even more stringent requirements for his social maturity are imposed by society. The main concern of adults is to raise a child correctly, that is, to teach him to do without us.

Usually, behind the psychological unpreparedness of parents for the child to leave the family lies an unconscious desire to maintain their power over him as long as possible, a sense of their own need for the child and his undivided belonging to the mother. They probably feel that they are not in demand in other areas of life - professionally!! or marital - and thus protect their idea ofyourself as a valuable, necessary and even powerful person. Often, a family rationalizes its reluctance to “let go” of the child with his weakness and illness. This family (usually maternal) selfishness issubjective the cause of poverty and limited social experience of younger schoolchildren. The child pays for the psychologically comfortable state of the mother, and pays at a high price.

But sooner or later the child will have to leave the “nest” - he must go to school. There he will discover a world in which a person constantly encounters prohibitions, subordination, rules and laws. Society, represented by the school, will present its demands to him. Then the child will regretfully understand that his parents hid life from him and did not prepare him well for it.

Even poor health cannot be a reason for a child’s social isolation. Parents, unfortunately, will not be able to be with their disabled child forever, and he, too, must learn to live in this society.

Social standard a child entering school assumes the following: “The child orients himself well in a new environment; is able to choose an adequate alternative behavior; knows the extent of his capabilities; knows how to ask for help and provide it; respects the wishes of other people, can participate in joint activities with peers and adults. He will not interfere with others with his behavior, he knows how to restrain himself and express his needs in an acceptable form. A socially developed child is able to avoid unwanted communication. He feels his place in the society of other people, understanding the different nature of the attitude of those around him; controls one’s behavior and methods of communication.”

Society, which is very lenient towards a preschooler, turns out to be quite harsh towards a seven-year-old or even a six-year-old child who has crossed the school threshold. For children with little experience of social relationships, going to school becomes a real stress.

The concept of “psychological readiness for school”

"School maturity"( schoolmaturity ), "readiness for school"( school readiness ) and “psychological readiness for school” - these concepts are used in psychology to indicate the level of mental development of a child, upon reaching which the latter can be taught at school.

Aboutintellectual maturity judged on the following grounds:

– differentiated perception (perceptual maturity), including identifying a figure from the background;

– concentration of attention;

– analytical thinking, expressed in the ability to comprehend the basic connections between phenomena;

– logical memorization;

– sensorimotor coordination;

– ability to reproduce a sample;

– development of fine hand movements.

Psychological prerequisites for learning at school include:quality of the child’s speech development. The development of speech is closely related to the development of intelligence and reflects both the general development of the child and the level of his logical thinking. We can say that intellectual maturity understood in this way largely reflects the functional maturation of brain structures.

Emotional maturity assumes:

– reduction of impulsive reactions;

– the ability to perform a not very attractive task for a long time.

ABOUTsocial maturity testify:

– the child’s need to communicate with peers and the ability to subordinate his behavior to the laws of children’s groups;

– ability to play the role of a student in a school learning situation.

The concept of “readiness for school” is ambiguous; readiness for school means that the child has the prerequisites for learning in the form of"introductory skills" . The latter represent the skills, knowledge, abilities, and motivation necessary for good mastery of the school curriculum.

Consider the child’s skills that arise on the basis of voluntary regulation of actions:

– the ability of children to consciously subordinate their actions to a rule that generally determines the method of action;

– ability to navigate a given system of requirements;

– the ability to listen carefully to the speaker and accurately complete tasks proposed orally;

– the ability to independently perform the required task according to a visually perceived model.

In fact, these are parameters for the development of voluntariness, which are part of psychological readiness for school, on which learning in the first grade is based.

School childhood, or primary school age. General characteristics of age

The beginning of primary school age is determined by the moment the child enters school. Accordingly, the boundaries of primary school age, coinciding with the period of study in primary school, are currently established from 6-7 to 9-10 years.

During this period, the further physical and psychophysiological development of the child takes place, providing the possibility of systematic education at school. First of all, the functioning of the brain and nervous system is improved. According to physiologists, by the age of 7 the cerebral cortex is already largely mature. However, the most important, specifically human parts of the brain, responsible for programming, regulation and control of complex forms of mental activity, have not yet completed their formation in children of this age (the development of the frontal parts of the brain ends only by the age of 12), as a result of which the regulatory and inhibitory influence of the cortex on subcortical structures is insufficient. The imperfection of the regulatory function of the cortex is manifested in the peculiarities of behavior, organization of activity and emotional sphere characteristic of children of this age: younger schoolchildren are easily distracted, are not capable of long-term concentration, are excitable, and emotional.

The beginning of schooling practically coincides with the period of the second physiological crisis, which occurs at the age of 7 years. A sharp endocrine shift occurs in the child’s body, accompanied by rapid body growth, enlargement of internal organs, and vegetative restructuring). This means that a fundamental change in the system of social relations and activities of the child coincides with a period of restructuring of all systems and functions of the body, which requires great tension and mobilization of its reserves.

However, despite certain complications noted at this time that accompany physiological restructuring (increased fatigue, the child’s neuropsychic vulnerability), the physiological crisis does not so much aggravate, but, on the contrary, contributes to a more successful adaptation of the child to new conditions. This is explained by the fact that the physiological changes taking place meet the increased demands of the new situation. Moreover, for those lagging behind in general development due to pedagogical neglect, this crisis is the last time when it is still possible to catch up with their peers.

At primary school age, there is unevenness in psychophysiological development in different children. Differences in the rates of development between boys and girls also remain: girls are still ahead of boys. Sometimes children of different ages sit at the same desk: on average, boys are a year and a half younger than girls, although this difference is not in calendar age.

The transition to systematic education places high demands on children’s mental performance, which is still unstable in younger schoolchildren and their resistance to fatigue is low. And although these parameters increase with age, in general, the productivity and quality of work of junior schoolchildren is approximately half lower than the corresponding indicators of senior schoolchildren.

The beginning of schooling leads to a radical change in the social situation of the child's development. The child’s entire system of life relationships is rebuilt and is largely determined by how successfully he copes with new demands.

The leader at primary school age becomeseducational activities. It determines the most important changes occurring in the development of the psyche of children at this age stage. Within the framework of educational activity, psychological neoplasms are formed that characterize the most significant achievements in the development of younger students and are the foundation that ensures development at the next age stage.

Primary school age is a period of intensive development and qualitative transformation of cognitive processes. The child gradually masters his mental processes, learns to control attention, memory, and thinking.

During primary school age, it begins to developa new type of relationship with people around you. The unconditional authority of an adult is gradually lost, peers begin to acquire more and more importance for the child, and the role of the children's community increases.

Thus,central neoplasms of primary school age are:

– a qualitatively new level of development of voluntary regulation of behavior and activity;

– reflection, analysis, internal action plan;

– development of a new cognitive attitude to reality;

– peer group orientation.

So the age of 6-12 years is considered as the period of transferring to the child systematic knowledge and skills that ensure introduction to working life and aimed at developing diligence. At this age, the child most intensively develops (or, on the contrary, does not develop) the ability to master his environment.

With a positive outcome of this stage of development, the child develops an experience of hisskill , if the outcome is unsuccessful –feeling of inferiority and inability to be equal to other people. Initiative, the desire to actively act, compete, and try their hand at different types of activities are noted as characteristic features of children of this age.

The profound changes occurring in the psychological appearance of a primary school student indicate the wide possibilities for the child’s development at this age stage. During this period, the potential of the child’s development as an active subject, learning about the world around him and himself, gaining his own experience of acting in this world, is realized at a qualitatively new level.

Junior school age issensitive for the development, formation, mastery and establishment of the following characteristics:

– motives for learning, development of sustainable cognitive needs and interests;

– productive techniques and skills of educational work, “ability to learn”;

– individual characteristics and abilities;

– skills of self-control, self-organization and self-regulation;

– adequate self-esteem, development of criticality towards oneself and others;

– social norms, moral development;

– communication skills with peers, establishing strong friendships.

The most important new formations arise in all areas of mental development: intelligence, personality, and social relationships are transformed. The leading role of educational activity in this process does not exclude the fact that the younger student is actively involved in other e types of activities (games, elements of work, sports, art, etc.), during which the child’s new achievements are improved and consolidated.

If at this age a child does not feel the joy of learning, does not acquire the ability to learn, does not learn to make friends, does not gain confidence in his abilities and capabilities, doing this in the future (outside the sensitive period) will be much more difficult and will require immeasurably higher mental and physical costs .

The more positive acquisitions a junior schoolchild has, the easier he will cope with the upcoming difficulties of adolescence.

Development of attention

A psychologist constantly hears complaints from teachers and parents about the inattention, lack of composure, and distractibility of children of this age. Most often, children aged 6-7 years old, i.e. first graders, receive this characteristic. Their attention is indeed poorly organized, has a small volume, and is poorly distributed and unstable, which is largely explained by the insufficient maturity of the neurophysiological mechanisms that ensure attention processes.

During primary school age, significant changes occur in the development of attention; all its properties are intensively developed: the volume of attention increases especially sharply (2.1 times), its stability increases, and switching and distribution skills develop. By the age of 9-10, children become able to maintain and carry out an arbitrary program of actions for a sufficiently long time.

Well-developed properties of attention and its organization are factors that directly determine the success of learning in primary school age. As a rule, well-performing schoolchildren have better indicators of attention development. At the same time, special studies show that various properties of attention have an unequal “contribution” to the success of learning in different school subjects. Thus, when mastering mathematics, the leading role belongs to the volume of attention; The success of mastering the Russian language is associated with the accuracy of attention distribution, and learning to read is associated with the stability of attention. This suggests a natural conclusion: by developing various properties of attention, it is possible to increase the performance of schoolchildren in various academic subjects.

The difficulty, however, is thatDifferent properties of attention can be developed to different degrees. The volume of attention is least affected; it is individual, while at the same time the properties of distribution and stability can and should be trained to prevent their spontaneous development.

The success of attention training is also largely determined byindividual typological features. It has been established that different combinations of properties of the nervous system can promote or, on the contrary, hinder the optimal development of attention characteristics. In particular, people with a strong and mobile nervous system have stable, easily distributed and switched attention. Individuals with an inert and weak nervous system are more likely to have unstable, poorly distributed and switchable attention.

However, the relatively weak development of the properties of attention is not a factor in fatal inattention, since the decisive role in the successful implementation of any activity belongs to (the organization of attention, i.e., the skill of “timely, adequate and effective use of the properties of attention in the process of performing various activities.” “And with objective weak properties of attention, the student can control it quite well. However, in these cases... management comes down mainly to constantly renewed efforts to maintain one’s scattered attention at the proper level, as well as to more or less successful self-control.

The inattention of younger schoolchildren is one of the most common reasons for poor performance. “Inattentional” mistakes in written work and during reading are the most offensive for children. In addition, they are the subject of reproaches and dissatisfaction from teachers and parents.

Therefore, inIclasses on the development of attention is recommended to be carried out primarily aspreventive, aimed at increasing the efficiency of attention functioning in all children. At subsequent stages of training (II– IVclasses), when the difficulties of the adaptation period are overcome, the importance of such work, of course, does not decrease, but along with it there arises the need to organize special classes with children who are particularly inattentive.

Classes on the formation of attention are conducted as training"attentive letter" and are based on the material of working with texts containing different types of errors “due to inattention”: substitution or omission of words in a sentence, substitution or omission of letters in a word, combined spelling of a word with a preposition, etc.

When working with inattentive schoolchildren, the development of individual properties of attention is of great importance. To conduct classes, a psychologist can use the following types of tasks.

1. Development of concentration. The main type of exercises are proofreading tasks, in which the child is asked to find and cross out certain letters in printed text. Such exercises allow the child to feel what it means to “be attentive” and develop a state of internal concentration. This work should be carried out daily (5 minutes per day) for 2-4 months. It is also recommended to use tasks that require identifying the characteristics of objects and phenomena (comparison technique); exercises based on the principle of exact reproduction of any pattern (sequence of letters, numbers, geometric patterns, movements, etc.); tasks like: “mixed up lines”, search for hidden figures, etc.

2. Increased attention span and short-term memory. The exercises are based on memorizing the number and order of a number of objects presented for a few seconds. As After mastering the exercise, the number of items gradually increases.

3. Attention distribution training. The basic principle of the exercises: the child is asked to simultaneously perform two multidirectional tasks (for example, reading a story and counting the strokes of a pencil on the table, completing a proofreading task and listening to a record of a fairy tale, etc.). At the end of the exercise (after 10-15 minutes), the effectiveness of each task is determined.

4. Development of the skill of switching attention. Carrying out proofreading tasks with alternating rules for crossing out letters.

Memory development

At primary school age, memory, like all other mental processes, undergoes significant changes. As already indicated, their essence is that the child’s memory gradually acquires the features of arbitrariness, becoming consciously regulated and mediated.

Now the child must remember a lot: learn the material literally, be able to retell it close to the text or in his own words, and in addition, remember what he has learned and be able to reproduce it after a long time. A child’s inability to remember affects his educational activities and ultimately affects his attitude towards learning and school.

First-graders (as well as preschoolers) have a well-developed involuntary memory, which records vivid, emotionally rich information and events in the child’s life. However, not everything that a first-grader has to remember at school is interesting and attractive for him. Therefore, immediate memory is no longer sufficient here.

There is no doubt that a child’s interest in school activities, his active position, and high cognitive motivation are necessary conditions for the development of memory. This is an irrefutable fact.

Improving memory in primary school age is primarily due to the acquisition during educational activities of various methods and strategies of memorization related to the organization and processing of memorized material. However, without special work aimed at developing such methods, they develop spontaneously and often turn out to be unproductive.

The ability of children of primary school age to voluntarily memorize is not the same throughout their education in primary school and varies significantly among studentsI– IIAndIII– IVclasses. Thus, for children 7-8 years old, “situations are typical when remembering without using any means is much easier than remembering by comprehending and organizing the material... Test subjects of this age are asked the questions: “How did you remember? What did you think about during the process of memorization? etc." – most often they answer: “I just remembered, that’s all.” This is also reflected in the productive side of memory... For younger schoolchildren, it is easier to carry out the “remember” attitude than the “remember with the help of something” attitude.”

As learning tasks become more complex, the “just remember” attitude ceases to justify itself, and this forces the child to look for methods of organizing memory. Most often, this technique is repeated repetition - a universal method that ensures mechanical memorization.

In elementary grades, where the student is required only to simply reproduce a small amount of material, this method of memorization allows one to cope with the academic load. But often it remains the only one for schoolchildren throughout the entire period of schooling. This is primarily due to the fact that at primary school age the child did not master the techniques of semantic memorization, his logical memory remained insufficiently formed.

The basis of logical memory is the use of mental processes as a support, a means of memorization. Such memory is based on understanding. In this regard, it is appropriate to recall the statement of L.N. Tolstoy: “Knowledge is only knowledge when it is acquired through the efforts of thought, and not through memory alone.”

The following mental methods of memorization can be used: semantic correlation, classification, highlighting semantic supports, drawing up a plan, etc., thus, before using, for example, the method of classification to memorize material, it is necessary to master classification as an independent mental action.

The process of development of logical memory atyounger schoolchildren should be specially organized, since the overwhelming majority of children of this age do not independently (without special training) use methods of semantic processing of material and, for the purpose of memorization, resort to a proven means - repetition. But even having successfully mastered the methods of semantic analysis and memorization during training, children do not immediately come to use them in educational activities. This requires special encouragement from an adult.

At different stages of primary school age, the dynamics of students’ attitudes towards the methods of semantic memorization they have acquired are noted: if second-graders, as mentioned above, do not need to use them independently, then by the end of their studies in elementary school, children themselves begin to turn to new methods of memorization when working with educational material.

In the development of voluntary memory of primary schoolchildren, it is necessary to highlight one more aspect related to the mastery at this age of sign and symbolic means of memorization, first of allwriting Anddrawing. As you master written language (towardsIII class) children also master mediated memorization, using such speech as a sign device. However, this process in younger schoolchildren “occurs spontaneously, uncontrollably, precisely at that crucial stage when the mechanisms of arbitrary forms of memorization and recollection take shape.”

Therefore, to master written speech, you need to compose, rather than retell texts. At the same time, the most appropriate type of word creation for children is composing fairy tales (Rodari J., 1990).

The younger school age is sensitive for the formation of higher forms of voluntary memorization, therefore, purposeful developmental work on mastering mnemonic activity is the most effective during this period.

Its important condition is to take into account the individual characteristics of the child’s memory: its volume, modality (visual, auditory, motor), etc. But regardless of this, every student must learn the basic rule of effective memorization: in order to remember the material correctly and reliably, it is necessary to actively use it work and organize it in some way.

V. D. Shadrikov AndL. V. Cheremoshkina identified 13 mnemonic techniques, or ways, of organizing memorized material: grouping, highlighting reference points, drawing up a plan, classification, structuring, schematization, establishing analogies, mnemonic techniques, recoding, completing the construction of memorized material, serial organization, associations, repetition.

It is advisable to provide primary schoolchildren with information about various memorization techniques and help them master those that will be most effective for each child.

The materials necessary for diagnosing memory and conducting developmental activities can be found in the specialized literature:L. M. Zhitp-nikova (1985), E.L. Yakovleva (1992), a series of books on memory developmentI. Yu. Matpyugina (1991) and others.

At primary school age, an intensive development process continuesmotor functions of the child . The most important increase in many indicators of motor development (muscular endurance, spatial orientation of movements, visual-motor coordination) is observed precisely at the age of 7-11 years.

Exercises to develop fine motor skills of the hand and hand-eye coordination:

– drawing graphic samples (geometric shapes and patterns of varying complexity);

– tracing along the contour of geometric shapes of varying complexity with sequential expansion of the stroke radius (along the outer contour) or narrowing it (outlining along the internal contour);

– cutting out shapes from paper along the contour (especially smooth cutting, without lifting the scissors from the paper);

– coloring and shading (as noted above, this most well-known technique for improving motor skills usually does not arouse interest among children of primary school age and therefore is used primarily only as an educational task (in the classroom). However, by giving this activity a competitive play motive, it can be successfully used it also outside of school hours);

– various types of visual arts (drawing, modeling, appliqué, etc.);

– designing and working with mosaics;

– mastering crafts (sewing, embroidery, knitting, weaving, working with beads, etc.).

Games and exercises for developing gross motor skills (strength, agility, coordination of movements):

– ball games (various);

– games with an elastic band;

Games like “Mirror”: mirror copying of the poses and movements of the leader (the role of the leader can be transferred to the child, who comes up with the movements himself); games like “Shooting Range”: hitting the target with various objects (ball, arrows, rings, etc.); the whole range of sports games and physical exercises; dance classes, aerobics. Special games and exercises for the development of motor skills in children are widely represented in the psychological and pedagogical literature.

How to help a younger student master his behavior

The child learns to actively manage himself, to build his activities in accordance with his goals, consciously made intentions and decisions.

The emergence of new forms of behavior is most directly related to educational activities, which, becoming mandatory for the child, determine the need to comply with a number of norms and rules, demanding to be organized, disciplined, etc. The ability to act voluntarily is formed gradually throughout the entire primary school age. Like all the higher And forms of mental activity, voluntary behavior obeys the basic law of their formation: new behavior first arises in joint activity with an adult, who gives the child the means to organize such behavior, and only then becomes the child’s own individual way of acting

The specificity of primary school age is that the goals of activity are set for children mainly by adults. Teachers and parents determine what a child can and cannot do, what tasks to complete, what rules to obey, etc. One of the typical situations of this kind is when the child performs some kind of assignment. Even among those schoolchildren (especially first-graders) who willingly undertake to carry out instructions from an adult, there are quite frequent cases when children do not cope with tasks because they have not learned its essence, quickly lost their initial interest in the task, or simply forgot to complete it on time.

These difficulties can be avoided if, when giving children any assignment, you follow certain rules.

Firstly, it is necessary that children, having received a task, immediately repeat it. This forces the child to mobilize, “tune in” to the task, better understand its content, and also take this task personally.

Secondly, you need to invite them to immediately plan their actions in detail, that is, immediately after the instruction, begin to carry it out mentally: determine the exact deadline for completion, outline the sequence of actions, distribute the work over days, etc.

A junior schoolchild is a person who is actively mastering communication skills . During this period, intensive establishment of friendly contacts occurs. Acquiring skills for social interaction with a peer group and the ability to make friends is one of the important developmental tasks at this age stage.

If a child by the age of 9-10 has established friendly relations with one of his classmates, this means that the child is able to establish close social contact with a peer, maintain relationships for a long time, and that communication with him is also important and interesting to someone.

The results of special studies show that attitudes towards friends and the very understanding of friendship have certain dynamics throughout primary school childhood (Kolominsky Ya. L., 1969). For children 5-7 years old, friends are, first of all, those with whom the child plays and whom he sees more often than others. The choice of a friend is determined primarily by external reasons: children sit at the same desk, live in the same house, etc. At this age, children pay more attention to behavior than to personality traits. When characterizing their friends, they indicate that “friends behave well”, “they are fun to be with.” During this period, friendly ties are fragile and short-lived, they easily arise and can quickly break off.

Between the ages of 8 and 11, children consider as friends those who help them, respond to their requests and share their interests. For the emergence of mutual sympathy and friendship, such personality traits as kindness and attentiveness, independence, self-confidence, and honesty become important.

Gradually, as the child masters school reality, he develops a system of personal relationships in the classroom. It is based on direct emotional relationships that prevail over all others.

Data from sociometric studies show that a student’s position in the system of interpersonal relationships that have developed in the classroom is determined by a number of factors common to different age groups. Thus, children who receive the largest number of choices from classmates (“stars”) are characterized by a number of common features: they have an even character, are sociable, have good abilities, are distinguished by initiative and rich imagination; most of them are good students; girls have an attractive appearance.

The group of schoolchildren who have a disadvantaged position in the system of personal relationships in the classroom also has some similar characteristics:

– such children have difficulties communicating with peers;

– they are quarrelsome, which can manifest itself as pugnacity,

– hot temper, capriciousness, rudeness, and isolation;

– They are often distinguished by snitching, arrogance, and greed;

– many of these children are sloppy and untidy.

The listed general qualities have certain specific manifestations at different stages of primary school age.

First-graders who are “unattractive” to their peers are characterized by the following characteristics: non-participation in the class asset; untidiness; poor academic performance and behavior; inconsistency in friendship; friendship with violators of discipline, as well as tearfulness.

First-graders evaluate their peers primarily by those qualities that are easily manifested externally, as well as by those that the teacher most often pays attention to.

By the end of primary school age, the eligibility criteria change somewhat. When assessing peers, social activity also comes first, in which children already value organizational skills, and not just the very fact of a social assignment given by the teacher, as was the case in the first grade, and, as before, beautiful appearance. At this age, certain personal qualities also become important for children: independence, self-confidence, honesty. It is noteworthy that indicators related to learning among third-graders are less significant and fade into the background.

For “unattractive” third-graders, the following traits are most significant: social passivity; unscrupulous attitude towards work, towards other people's things.

The criteria for assessing classmates characteristic of younger schoolchildren reflect the peculiarities of their perception and understanding of another person, which is associated with the general patterns of development of the cognitive sphere at this age: poor ability to highlight the main thing in a subject, situational nature, emotionality, reliance on specific facts, difficulties in establishing cause-and-effect relationships etc.

The increasing role of peers by the end of primary school age is also evidenced by the fact that at the age of 9-10 (unlike younger children), schoolchildren are much more sensitive to comments received in the presence of classmates, they become more shy and begin to be embarrassed not only by insignificant adults , but also unfamiliar children of their own age.

The system of personal relationships is the most emotionally intense for each person, since it is associated with his assessment and recognition as an individual. Therefore, an unsatisfactory position in a peer group is experienced very acutely by children and is often the cause of inadequate affective reactions (Slavina L. S., 1966). However, if a child has at least one mutual attachment, he ceases to be aware and does not really experience his objectively bad position in the system of personal relationships. Even a single mutual choice is a kind of psychological protection and can balance several negative choices, since it turns the child from “rejected” to accepted.

In the elementary grades, maladaptation is usually closely related to the failure of educational activities. It is no coincidence that academic failure is considered both a manifestation and a cause of psychogenic school maladaptation in primary school age. A child with limited ability to adapt to a new situation - a learning situation, the requirements and communication style of a teacher, will have insufficiently developed methods of educational work, and gaps in knowledge may appear - hence low educational performance. On the other hand, if there are difficulties in mastering educational material, a lag in learning gives rise to maladaptation, and indirectly - through negative assessments of people significant to the student, teachers and parents.

School failure is an acute problem in primary school. It is called early failure, in contrast to late failure, which appears during the transition to the middle class. Since educational activity is the leading one at primary school age, determining the differentiation of cognitive processes and personal changes, early academic failure becomes a source of a wide range of problems and affects the development of the child’s personality as a whole.

Educationally neglected children have normal intellectual development, sometimes even quite high potential in some areas. But due to the lack of the necessary base (knowledge, abilities, skills), they cannot demonstrate their strengths in the learning process and give the impression of being of little ability. It is relatively easy to help them organize educational activities and achieve success: they accept help and quickly learn what they were not given in preschool childhood. If pedagogical neglect is combined with mental retardation, special learning conditions are required.

Sometimes the primary cause of school failure may be disorders of the analytical systems (poor vision, poor hearing); somatic weakness of the sick child, including asthenic conditions; some properties of higher nervous activity that complicate educational work, such as hyperactivity or slowness. A number of features of psychophysiological development, for example, left-handedness, do not directly cause academic failure, but when Unfavorable circumstances (retraining a left-handed child) contribute to this.

Literature

Wenger A.L., Tsukerman G.A.. Psychological examination of primary schoolchildren. - M.: Vlados-Press, 2005. - 159 p.

Volkov B.S. Junior schoolchild: How to help him study. – M.: Academic Project, 2004. - 142 p.

Matyukhina M.V. Motivation for teaching of younger schoolchildren. - M., 1984. – 126 p.

Junior schoolchild: development of cognitive abilities./Ed. AND.V. Dubrovina. Teacher's manual. – M.: Education, 2003. – 148 p.

Mukhina V.S. Child psychology: Textbook. for pedagogical students in-tov/Ed. L.A. Wenger. - 2nd ed., revised. and additional – M.:Education, 1985. – 272 p.

Ovcharova R.V. Practical psychology in elementary school. – M.: Sphere shopping center, 1996. – 240 p.

In psychology - child and pedagogical, one of the central places is occupied by the problem of psychological characteristics of younger schoolchildren. Knowledge and consideration of the psychological characteristics of children of primary school age will make it possible to correctly organize educational work in the classroom. Therefore, everyone should know these features and take them into account in their work and when communicating with primary school children.

Junior school age is the age of 6-11 year old children studying in grades 1–4 of primary school. The boundaries of age and its psychological characteristics are determined by the educational system adopted for a given time period, the theory of mental development, and psychological age periodization (D.B. Elkonin, L.S. Vygotsky).

Currently, there is no single theory that can give a complete picture of the mental development of a child in different periods. Therefore, to obtain a complete picture of the development, behavior and upbringing of children, several theories were analyzed that affect the periodization of primary school age.

L.S. Vygotsky based the periodization of a child’s mental development on the concept of leading activity. At each stage of mental development, leading activity is of decisive importance. At the same time, other types of activities do not disappear - they exist, but they exist in parallel and are not the main ones for mental development.

S. Freud in psychoanalytic theory explained personality development by the action of biological factors and the experience of early family communication. Children go through 5 stages of mental development, at each stage the child's interests are focused around a specific part of the body. The age of 6 - 12 years corresponds to the latent stage. Thus, younger schoolchildren have already formed all those personality qualities and response options that they will use throughout their lives. And during the latent period, his views, beliefs, and worldview are “honed” and strengthened. During this period, the sexual instinct is supposedly dormant.

According to cognitive theory (Jean Piaget), a person goes through 4 large periods in his mental development:

1) sensory-motor (sensorimotor) - from birth to 2 years;

2) preoperative (2 - 7 years);

3) period of concrete thinking (7 - 11 years);

4) period of formal-logical, abstract thinking (11-12 - 18 years and beyond)

According to Piaget, the third period of mental development occurs between the ages of 7 and 11 years—the period of specific mental operations. The child's thinking is limited to problems relating to specific real objects.

The beginning of schooling means a transition from play activity to educational activity as the leading activity of primary school age, in which the main mental new formations are formed. Therefore, entering school makes major changes in a child’s life. His entire way of life, his social position in the team and family changes dramatically. Teaching becomes the main, leading activity, the most important duty is the duty to learn and acquire knowledge. This is serious work that requires organization, discipline, and strong-willed efforts of the child.

Features of thinking. Primary school age is of great importance for the development of basic mental actions and techniques: comparison, identification of essential and non-essential features, generalization, definition of a concept, identification of consequences and causes (S.A. Rubinstein, L.S. Vygotsky, V.V. Davydov) . The lack of full-fledged mental activity leads to the fact that the knowledge acquired by the child turns out to be fragmentary, and sometimes simply erroneous. This seriously complicates the learning process and reduces its effectiveness (M.K. Akimova, V.T. Kozlova, V.S. Mukhina).

V.V. Davydov, D.V. Elkonin, I.V. Dubrovina, N.F. Talyzina, L.S. Vygotsky wrote that during primary schooling, thinking, especially verbal-logical thinking, develops most actively. That is, thinking becomes the dominant function at primary school age.

Peculiarities of perception. The development of individual mental processes occurs throughout primary school age. Children come to school with developed perception processes (simple types of perception have been formed: size, shape, color). For younger schoolchildren, the improvement of perception does not stop; it becomes a more controlled and targeted process.

Features of attention. Age-related characteristics of the attention of younger schoolchildren are the comparative weakness of voluntary attention and its low stability. Involuntary attention is much better developed in younger schoolchildren. Gradually, the child learns to direct and steadily maintain attention on the necessary, and not just externally attractive objects. The development of attention is associated with the expansion of its volume and the ability to distribute attention between different types of actions. Therefore, it is advisable to set educational tasks in such a way that the child, while performing his actions, can and should monitor the work of his comrades.

Features of memory. The memory productivity of younger schoolchildren depends on their understanding of the nature of the task and on mastering the appropriate techniques and methods of memorization and reproduction. The ratio of involuntary and voluntary memory in the process of their development within educational activities is different. In 1st grade, the effectiveness of involuntary memorization is higher than voluntary, since children have not yet developed special techniques for meaningful processing of material and self-control. As the techniques of meaningful memorization and self-control are formed, voluntary memory in second and third graders turns out to be more productive in many cases than involuntary memory.

Features of imagination. Systematic educational activities help children develop such an important mental ability as imagination. The development of imagination goes through two main stages. Initially, the reconstructed images very roughly characterize the real object and are poor in details. The construction of such images requires a verbal description or picture. At the end of the 2nd grade, and then in the 3rd grade, the second stage begins, and this is facilitated by a significant increase in the number of signs and properties in the images.

Like other mental processes, the general nature of children’s emotions changes in the context of educational activities. Educational activity is associated with a system of strict requirements for joint actions, with conscious discipline and with voluntary attention and memory. All this affects the emotional world of the child. During primary school age, there is an increase in restraint and awareness in the manifestations of emotions and an increase in the stability of emotional states.

Primary school age is a period of accumulation, absorption of knowledge, a period of acquiring knowledge primarily. At this age, imitation of many statements and actions is a significant condition for intellectual development. Particular suggestibility, impressionability, focus of mental activity of younger schoolchildren on repetition, internal acceptance, creation of suitable conditions for the development and enrichment of the psyche. These properties, in most cases, are their positive side, and this is the exceptional uniqueness of this age. Consequently, entering school contributes to the formation of the need for recognition and knowledge, to the development of a sense of personality.

Bibliography:

1. V.S. Mukhina, Developmental psychology. - 4th ed., - M.: Academia, 1999. - 456 p.

2. N. Semago, M. Semago, Theory and practice of assessing the mental development of a child. Preschool and primary school age. – St. Petersburg: Rech, 2010. – 385 p.

3. L.S. Vygotsky, Psychology of human development. - M.: Eksmo Publishing House, 2005. - 1136 p.

4. D.B. Elkonin, Selected psychological works. - M.: Pedagogy, 1989. - 560 p.

5. P.P. Blonsky, Psychology of junior schoolchildren. - Voronezh: NPO "MODEK", 1997. - 575 p.

Junior school age is the beginning of school life. The boundaries of primary school age, coinciding with the period of study in primary school, are currently set from 6-7 to 9-10 years. Physical development, a stock of ideas and concepts, the level of development of thinking and speech, the desire to go to school - all this creates the prerequisites in order to study systematically.

At this age, there is a change in image and lifestyle compared to preschool age: new requirements, a new social role for the student, a fundamentally new type of activity - educational activity. At school, he acquires not only new knowledge and skills, but also a certain social status. The perception of one’s place in the system of relationships changes. The interests, values of the child, and his entire way of life change.

From a physiological point of view, this is a time of physical growth, when children quickly grow upward, there is disharmony in physical development, it is ahead of the child’s neuropsychic development, which affects the temporary weakening of the nervous system. Increased fatigue, anxiety, and increased need for movement appear.

Social situation of development at primary school age:

1. Educational activity becomes the leading activity.

2. The transition from visual-figurative to verbal-logical thinking is completed.

3. The social meaning of the teaching is clearly visible (in the attitude of young schoolchildren to grades).

4. Achievement motivation becomes dominant.

5. There is a change in the reference group compared to preschool age.

6. There is a change in the daily routine.

7. A new internal position is strengthened.

8. The child’s system of relationships with people around him changes.

Leading activity at primary school age - educational activities. Its characteristics: effectiveness, commitment, arbitrariness. As a result of educational activities, there arise mental neoplasms: arbitrariness of mental processes, reflection (personal, intellectual), internal plan of action (mental planning, ability to analyze).

V.V. Davydov formulated the position that the content and forms of organization of educational activities project a certain type of consciousness and thinking of the student. If the content of training is empirical concepts, then the result is the formation of empirical thinking. If learning is aimed at mastering a system of scientific concepts, then the child develops a theoretical attitude to reality and, on its basis, theoretical thinking and the foundations of theoretical consciousness.

The central line of development is intellectualization and, accordingly, the formation of the mediation and arbitrariness of all mental processes. Perception is transformed into observation, memory is realized as voluntary memorization and reproduction based on mnemonic means (for example, a plan) and becomes semantic, speech becomes arbitrary, the construction of speech utterances is carried out taking into account the purpose and conditions of speech communication, attention becomes arbitrary. The central new formations are verbal-logical thinking, verbal discursive thinking, voluntary semantic memory, voluntary attention, and written speech.

At primary school age, children are able to concentrate, but their involuntary attention still predominates.

The arbitrariness of cognitive processes occurs at the peak of volitional effort (it specially organizes itself under the influence of requirements). Attention is activated, but not yet stable. Maintaining attention is possible thanks to volitional efforts and high motivation.

7-8 years is a sensitive period for the assimilation of moral norms (the child is psychologically ready to understand the meaning of norms and rules and to implement them on a daily basis).

Self-awareness develops intensively. The formation of self-esteem of a junior schoolchild depends on the performance and characteristics of the teacher’s communication with the class. The style of family education and the values accepted in the family are of great importance. Excellent students and some well-achieving children develop inflated self-esteem. For underachieving and extremely weak students, systematic failures and low grades reduce self-confidence in their abilities. They develop compensatory motivation. Children begin to establish themselves in another area - in sports, music.

A characteristic feature of the relationships between younger schoolchildren is that their friendship is based, as a rule, on common external life circumstances and random interests (children sit at the same desk, live in the same house, etc.). The consciousness of younger schoolchildren has not yet reached the level where the opinion of their peers serves as a criterion for truly assessing oneself.

It is at this age that a child experiences his uniqueness, he recognizes himself as an individual, and strives for perfection. This is reflected in all spheres of a child's life, including relationships with peers. Children find new group forms of activity, classes. At first, they try to behave as is customary in this group, obeying the laws and rules. Then begins the desire for leadership, for superiority among peers. At this age, friendships are more intense but less durable. Children learn the ability to make friends and find a common language with different people.

At primary school age, the child’s personality is intensively formed. If in the first grade personal qualities are still poorly expressed, then by the end of the third and beginning of the fourth year of study, the child’s personality is already clearly manifested in the system of values and relationships with peers and adults. The incentive for developing a child’s value system is the expansion of social connections and meaningful relationships. The attitude towards school and learning has a central and system-forming position. Depending on the sign of these relationships, either socially normative or deviant and accentuated personality variants begin to take shape. The biggest contribution to development along a deviant path is made by school maladjustment and academic failure. As has been repeatedly noted, at the end of the first grade a group of students with pronounced neurotic and psychosomatic manifestations becomes noticeable. This group is at risk for socially deviant development, since the vast majority of schoolchildren in this group have already formed a negative attitude towards school and learning.

Frequently experienced negative emotions associated with poor performance and punishment from parents for school success, as well as the threat of decreased self-esteem, stimulate the acceleration of the formation of a psychological defense system.

The works of the American school of psychoanalysis, in particular F. Kramer, indicate the possibility of activating more mature and typologically weakly determined ego-defense mechanisms, such as projection. The functions of projection are associated with the division of the evaluative components of any event that happened to the child into negative and positive. At the same time, completely automatically and without the participation of control from consciousness and self-awareness, the negative component is transferred to any participant in the events, who is assigned a negative role in their development. The positive side of the same event remains in the child’s memory and is included in the cognitive component of his “I-concept”. Such properties of projection lead to the fact that the primary school student does not develop the necessary personality qualities.

Responsibility and the ability to admit your mistakes. Responsibility is transferred, as a rule, either to parents or to teachers, who are to blame for the child’s failures. In other words, projection allows the “loser” to maintain his self-esteem and does not make him aware of what is actually slowing down his personal development.

The second common form of psychological defense that protects a primary school student from a decrease in self-esteem due to low academic performance is denial. Activation of denial distorts incoming information by selectively blocking unnecessary or dangerous information that threatens the child’s psychological well-being. Outwardly, such a child gives the impression of being extremely absent-minded and inattentive in situations of communication with parents and teachers, when they are trying to get an explanation from him about his offenses. Denial does not allow the child to receive objective information about himself and about current events, and distorts self-esteem, making it inadequately inflated.

At primary school age, communication with peers becomes increasingly important for a child’s development. In a child’s communication with peers, not only cognitive subject-related activities are more readily carried out, but also the most important skills of interpersonal communication and moral behavior are formed. The desire for peers and the thirst for communication with them make the peer group extremely valuable and attractive for a student. They value their participation in the group very much, which is why sanctions from the group applied to those who have violated its laws become so effective. In this case, very strong, sometimes even cruel, measures of influence are used - ridicule, bullying, beatings, expulsion from the “collective”.

It is at this age that the socio-psychological phenomenon of friendship manifests itself as an individually selective deep interpersonal childhood relationship, characterized by mutual affection based on a feeling of sympathy and unconditional acceptance of the other. The most common is group friendship. Friendship performs many functions, the main ones being the development of self-awareness and the formation of a sense of belonging, connection with a society of one’s own kind. Ya.L. Kolominsky proposes to consider the so-called first and second circles of communication of schoolchildren. The first circle of communication includes “those classmates who are the object of a stable choice for him, for whom he feels constant sympathy and emotional attraction.” Among the remaining ones, there are those whom the child constantly avoids choosing for communication, and there are those “in relation to whom the student hesitates, feeling more or less sympathy for them.” These latter constitute the student’s “second social circle.”