Historical culinary excursion: what they ate and drank in the Middle Ages. What they ate in the Middle Ages Common peasant food in the early Middle Ages

Looking at medieval engravings or reading the literature of this era, we involuntarily raise the question of how the difficult life of a medieval person was organized. How people ate at that time, what dishes were the most common, and whether the food for the peasants and the nobility differed. Medieval chroniclers, illustrations, and historical research help shed light on many aspects of medieval cuisine.

Greens were most often consumed raw (onions of different varieties, sorrel, parsley). Carrots were most often boiled with pieces of meat, and legumes were eaten in large quantities, especially among the peasantry, simply by boiling them. Raspberries and wild strawberries were especially popular. The orchards grew cherries and plums.

Beef and pork meat was consumed both separately and as a filling for pies. Cheese was often added to them. Wealthy people ate flat white loaves made from wheat flour, while the villagers were content with bread made from rye flour. In times of famine, bread was replaced with pea cakes, to which oats and acorns were added. Porridge was cooked from lentils, after soaking it.

Milk and its derivatives were more often food for the villagers, and not for the rich townspeople and the nobility. City artisans could have breakfast with fish, bread cakes, ale or cheese, dine with hot meat, often boiled soup. The simpler people usually dined with what was left from breakfast and lunch.

The nobility could eat more varied, not only beef and pork meat. The diet of rich people included all game, without exception. It is known that the nobles themselves loved to hunt and arranged whole games or festive events in someone's honor from hunting. On Wednesday, Friday and Saturday, the devout nobles always fasted, so they had to be content with fish (most often they were pike and carp).

The poor population could not afford to season meat with spices, but they were available to the nobility and the middle class of the population. Cane sugar had already been brought to the European continent, and honey also did not lose its popularity. The cost of almonds, cinnamon, cloves and peppers was very high.

One of the interesting components of the feast among the nobility was bread plates - trenchers. They were not eaten, they served as coasters for the rest of the food, and the servants cut the trenchers. After the meal, they, along with the remnants of other food and sauces, were given to the poor or animals. They were baked from very coarse flour - especially in order to make it more convenient to put food on them.

If the nobility could afford to eat meat almost daily, the peasants "got hold of" meat much less frequently. Basically, they ate rye bread and sheep cheese, nuts, berries and fruits. Hot in peasant families was served only once a day: usually it was a stew made from grains, where vegetables were added, and on holidays - meat.

An interesting fact: Medieval doctors believed that two meals a day would be enough for all segments of the population. This, they believe, prevents overeating and health problems. In addition, constantly maintaining a fire in the hearth was a very troublesome task. Also, doctors of the Middle Ages advised to sit down to eat again only if a person feels hungry. This meant that the earlier food had already left the body. If a person started a meal when the previously eaten food did not have time to be digested, it was considered harmful. Maybe we should heed similar advice in order not to overeat.

is a multifaceted and symbolic phenomenon. Lush feasts of the estate elite emphasized their authority and prestige. The inhabitants of the monasteries had strict prescriptions for the daily diet. And the menu of the "silent majority" causes a lot of guesswork: in a time when there was no quality fast food and many hours of daily manual labor was mandatory, the issue of a balanced diet was very acute.

Two food poles

The gastronomic world of ordinary Europeans in the 5th-14th centuries consisted of two hemispheres. This situation was due not only to climate, but also to culture, namely mythology. In the north, among dense forests and near the cold seas, the barbarians lived. The Germanic tribes obtained food mainly through hunting and pastoralism, although in some areas there was settled agriculture, which continued to develop locally from the Early Middle Ages.

Feast of the Germanic tribe. (wikipedia.org)

In cultural terms, the meat diet was dictated from above: the plots of German-Scandinavian mythology tell us about feasts in the halls of the one-eyed Odin, where the Einherchians who fell in glorious battles ate the meat of the wonderful boar Sehrimnir, which did not end, and washed down with delicious honey milk of the goat Heidrun. The northerners observed church fasts very poorly because of the good tradition of eating mainly meat products, while the inhabitants of warm regions endured the hardships prescribed by the church quite tolerably.

Southern food habits were based on the Greco-Roman, Mediterranean tradition. Vegetables and fruits were the basis of the cuisine of the sunny Balkans, the Apennine Peninsula and the Pyrenees. The inhabitants of the Mediterranean imagined paradise in the form of a garden in which the most rare and unusual delicacies grew. Between the XII-XIV centuries, "information" appeared about the country with milk rivers and jelly banks - Kokani. There, allegedly, food fell on heads from the sky and hung on trees, and fat geese and pork hams grew from the ground like wheat.

Dreams of food prosperity were dictated by the realities of the High Middle Ages. The rapid growth of the population and a number of significant social upheavals in the XIV-XVI centuries. exacerbated the problems of finding food and began to gradually erase the boundaries.

"Eat, Pray, Work"

The adult human body requires 2,500 to 4,000 calories per day. In a huge complex of sources, one can find information about the nutritional value of the diet of workers: a peasant of the 9th century, like a night guard in the 14th century, received approximately 6,000 calories, a plowman or a sailor could afford more than 3,500 calories. Despite the sudden cataclysms and crop failures, they ate more than enough, but the quality of food left much to be desired: protein was in short supply, carbohydrates prevailed.

Peasants eat bread. (wikipedia.org)

Bread is the head of everything. On this principle, the diet of a commoner was kept. Forms of bread were presented widely: loaves, loaves, balls, biscuits. It has also been used as an additive in soup, porridge, and stews. The peasant was content with bread made from a mixture of wheat and rye. Every day a simple worker ate from 1.6 to 2 kg of the product.

Connoisseurs of Italian cuisine should be aware that pasta has been on the menu since the Early Middle Ages. As a rule, “small grains” were added to the dish - beans, peas, lentils. Then the level of carbohydrate content in food doubled.

Vegetables were an important part of the diet of the average peasant family. Cabbage is a symbol of love among mere mortals. It was customary to call beloved ones “my cabbage!”, Which indicates the high status and exquisite taste of this vegetable. Followed by garlic, turnips, leeks, carrots, parsnips, cucumber, asparagus and spinach.

When it comes to meat food on the table of a commoner, a lot of questions arise. It would seem that without animal proteins it was very tight, and it would be necessary to keep cattle or poultry. However, not all rural households could feed pigs, geese, chickens or sheep. Meat rarely stayed on peasant tables. As a rule, it was added to soup or served as corned beef. Findings of archaeologists who studied the garbage pits of yards speak about the origin of meat: anything was used for food. Horse and dog meat did not shy away.

The use of meat had climatic and regional characteristics: in the cold they ate salted pork and pork sausages, they ate lamb in the summer. Although hunting was the lot of the powerful, sometimes, near the forests, commoners could afford to eat venison. 80-100 grams of meat per day is the norm for a resident of a medieval European village.

With fish, things were much worse: the monopoly on fishing belonged either to the lords or to the holders of large church dioceses. Archaeological studies have shown that there were actually no fish bones near peasant households. However, there are references in the sources about carps, perches, eels, pikes. Less often about herring, salmon and whiting. Seafood was not very popular, but still commoners who lived by the sea could taste oysters and mussels. For medieval man, eating frogs and snails was not something out of the ordinary.

Cheese was a symbol of medieval dairy products. Europeans have already identified several varieties: Dutch, Brie, Chester, Parmesan. Milk in its pure form was completely unsuitable as a food product, but in sour milk it was added to soup. Butter remained unusable in the Middle Ages: it was replaced by melted lard or vegetable fat from walnuts, poppies or olives.

Peasant life. (spartacus-educational.com)

The range of products in the peasant diet proves that the vast majority of ordinary people ate cereals and soups every day. A light breakfast could consist of a slice of cheese and a piece of bread. Some meat and a hearty bean porridge with vegetables or herbs could be served at the end of the daily chores. On holidays, everything that was put on the tables - the people could fill their belly with both ordinary soups and rare meat delicacies. Of course, everything was swept off the table. After such events, the family could only eat “holy spirit” for months.

"Who drinks not with us, he drinks against us"

What should a simple worker of fields and gardens drink? Water in wells and springs, of course, was valued, but it remained far from accessible to everyone. Fresh water brought with it a lot of trouble for the stomach and intestines - it was treated with caution.

Medieval feast. (blogs.getty.edu)

Another thing is “liquid bread”. In the 13th century, beer gained wide popularity. Of course, it was different from modern varieties. Fermented oats produced British beer and North German ales, while the combination of barley and hops gave the world light varieties.

The main drink of the medieval West was wine, a barrel of which lay in every cellar. Of course, the modern variety of varieties did not exist. They mostly drank white wine. Pink varieties were rare, and red ones remained the lot of secular rulers. The wine had a tart taste and could vaguely resemble the products of ancient winemakers. The fortress of medieval wine did not exceed 7-10 degrees. It was stored for no more than a year in tarred barrels, otherwise it turned sour. Accordingly, with such a shelf life, everyone drank wine in large quantities: the daily dose of consumption was from one to three liters.

"There are no bad foods, there are bad chefs"

A resident of a medieval village was not a gourmet and watched his diet only during fasting. But not everyone strictly followed the church prescriptions and ate high-calorie dishes with pleasure and washed them down with intoxicating drinks.

Crop failures, epidemics, wars and bad weather conditions affected the amount of food in village houses, but the sin of gluttony remained the main enemy of the peasants. Imperfect culinary skills in the preparation of heavy and high-calorie foods also played a negative role. There was no time to follow the figure, and the church did not particularly allow it. Having stuffed his stomach with a nutritious mass of bread, cheese, porridge or soup, a simple villager went to work in the field or graze cattle. After all, the basis of his being is work.

Guys, we put our soul into the site. Thanks for that

for discovering this beauty. Thanks for the inspiration and goosebumps.

Join us at Facebook And In contact with

Beer instead of water, beavers instead of fish and a lot of cereals - these are far from all the distinctive features of the cuisine of the inhabitants of medieval Europe. Today, when the ingredients for almost any dish can be bought at the store closest to the house, and thanks to the variety of cooking methods and kitchen gadgets, everyone can feel like a chef, it is interesting to imagine how we would have behaved in the Middle Ages, when there were neither modern technologies for storing food, nor a variety of ways to cook them.

website I tried to find out the most reliable information about the medieval menu of Western Europe, with which we want to introduce you today. And at the end we will offer a recipe for a delicious medieval stew.

1. Meat

When there was no fast, fried meat of domestic animals often appeared on the table of a European. Beef was the least likely to be seen, because the breeding of cows in the Middle Ages required a lot of effort, besides, at that time, milk and the labor force of cattle were valued higher than their meat.

As a rule, pork was served at the table. However, in addition to the tenderloin or bacon that we are used to, the most “unexpected” parts of the pig body could be on the dish: snout, ears, tail, or even genitals.

Those who were born into a wealthy family or into a family of hunters often had the opportunity to cook game and rabbit meat, adored by medieval Europeans. She was valued not only because of her taste, but also because she was allowed to eat in fasting.

Most often, the meat was roasted on a spit over an open fire. Sausages could be made from the leftovers: they prepared it by stuffing pork intestines with chopped offal, lard and meat.

2. Fish

The fish menu of those years of a modern person can lead to a stupor. Medieval Europeans were really sure that beavers and water birds were also fish. However, this list also included species of fish quite familiar to a person of the 21st century: pike, trout, herring or cod, depending on what was found in a particular area.

Before getting to the table, the fish was stored in a dried form: it was gutted, salted, hung on a pole and left in this state until it hardened. And before cooking, the fish was beaten with a hammer and soaked in water so that it did not taste “rubber”.

3. Side dishes

In medieval Europe, potatoes appeared rather late and there was very little rice, since it had not been grown in these territories for a long time.

But you could treat yourself to buckwheat or pasta, the existence of the latter is confirmed, for example, by the Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio. Before serving, the pasta was boiled for a long time in boiling water, broth or milk, and then sprinkled with sugar.

Those who did not like these types of side dishes could supplement the food with beans. There were plenty of them all over Europe.

4. Kashi

Porridges were cooked in any home, regardless of what class the family belonged to. It was from porridge that medieval Europeans received the largest portion of their daily calories. Kashi was cooked from any available type of grain. By the way, they were not only for breakfast: porridge boiled in almond milk with sugar could well be served as a dessert.

5. Bread

Do you eat bread? And if so, which one do you prefer: white, gray or black? However, in the Middle Ages you would not have to choose, because the estate would have done it for you: only the rich could afford white bread made from wheat flour. Poor families were content with rye bread.

After a meal, broth, gravy and even wine could be absorbed into a piece of bread. From flat cakes, by the way, you can cook a separate dish by boiling them in broth and sprinkling with spices.

6. Sweets

Today, caramelized apples can be found both in the restaurant menu and on the home table. The ancestor of this dish was a very popular dessert in medieval Europe. Only then apples and other fruits were often watered not with syrup, but with honey. Mulled wines and small sweets made from berries in sugar were also served as desserts.

In general, in the Middle Ages, Europeans had something to sweeten their lives. A variety of sugar pancakes, fritters, sweet spreads, quiches and, as we wrote above, sweetened cereals - you could choose anything from this list. If the family could not afford meals with sugar, fruits and berries were used as sweeteners.

7. Dairy products

Despite the fact that milk was available to people of almost all classes, it was not intended for adults. It was mainly used by the elderly and children. Mature people could drink what was left during the production of butter, or milk that began to turn sour. It turned sour, by the way, quite often due to the lack of storage capacity.

Instead of animal milk, almond milk could well have been used for cooking. In the Middle Ages, cheese making was well developed: parmesan, brie, edam, ricotta were available even to representatives of the lower classes.

8. Drinks

Do you try to drink at least 8 glasses of water a day? Then in the Middle Ages you would have had a hard time. At this time, water was not popular for several reasons: it was difficult to purify it, it was not recommended by doctors, and it was simply not prestigious. Many have replaced water with alcohol. It could be wine, which was more often drunk by the rich and vineyard owners, or beer, which was also available to poorer people.

Every year there is a higher and higher level of preparation for medieval festivals. The most severe requirements are imposed on the identity of the costume, shoes, tent, household items. However, for a stronger immersion in the environment, it would be good to adhere to other rules of the eras. One of them is identical food. It happens that the reenactor spends money on the costume of a rich nobleman, selects a yard (team), entourage, and buckwheat porridge in a bowler hat and on the table.

What did the inhabitants of various classes of the city and village eat in the Middle Ages?

In the XI-XIII centuries. the food of most of the population of Western Europe was very monotonous. They especially ate a lot of bread. Bread and wine (grape juice) were the main staples of the unprivileged population of Europe. According to French researchers, in the X-XI centuries. secular persons and monks consumed 1.6-1.7 kg of bread per day, which was washed down with a large amount of wine, grape juice or water. Peasants were often limited to 1 kg of bread and 1 liter of juice per day. The poorest drank fresh water, and so that it would not go rotten, they put marsh plants containing ether - aronnik, calamus, etc. into it. A wealthy city dweller in the late Middle Ages ate up to 1 kg of bread daily. The main European cereals during the Middle Ages were wheat and rye, of which the former prevailed in Southern and Central Europe, the latter in Northern Europe. Barley was extremely widespread. The main grain crops significantly supplemented spelt and millet (in the southern regions), oats (in the northern regions). In Southern Europe, mainly wheat bread was consumed, in Northern Europe - barley, in Eastern Europe - rye. For a long time, bread products were unleavened cakes (bread in the form of a long loaf and carpets began to be baked only towards the end of the Middle Ages). The cakes were hard and dry because they were baked without yeast. Barley cakes were preserved longer than others, so warriors (including crusader knights) and wanderers preferred to take them on the road.

|

|

| Medieval mobile bread maker 1465-1475. Most of the ovens were naturally stationary. | The feast in the Matsievsky Bible (B. M. 1240-1250) looks very modest. Whether the features of the image. Whether in the middle of the 13th century it was difficult with food. |

|

|

| They kill the bull with a hammer. "Book of Trecento Drawings" Tacuina sanitatis Casanatense 4182 (XIV century) | Fish seller. "Book of Trecento Drawings" Tacuina sanitatis Casanatense 4182 (XIV century) |

|

|

| Feast, page detail January, Book of Hours by the Limburg brothers, cycle "The Seasons". 1410-1411 | Vegetable trade. Hood. Joachim Beuckelaer (1533-74) |

|

|

| Dance among the eggs, 1552. thin. Aertsen Pieter | The interior of the kitchen from the parable of the feast, 1605. Hood. Joachim Wtewael |

|

|

| Fruit merchant 1580. Art. Vincenzo Campi Vincenzo Campi (1536–1591) | Fishwife. Hood. Vincenzo Campi Vincenzo Campi (1536–1591) |

|

|

| Kitchen. Hood. Vincenzo Campi Vincenzo Campi (1536–1591) | Game shop, 1618-1621. Hood. Franz Snyders Franz Snyders (with Jan Wildens) |

The bread of the poor differed from the bread of the rich. The first was predominantly rye and of low quality. Wheat bread made from sifted flour was common on the table of the rich. Obviously, the peasants, even if they grew wheat, hardly knew the taste of wheat bread. Their lot was rye bread made from poorly ground flour. Often, bread was replaced with cakes made from flour of other cereals, and even from chestnuts, which played the role of a very important food resource in Southern Europe (before the appearance of potatoes). In famine years, the poor added acorns and roots to bread.

Next in frequency of consumption after bread and grape juice (or wine) were salads and vinaigrettes. Although their components were different than in our time. Of the vegetables, the main plant was the turnip. It has been used since the 6th century. in raw, boiled and mushy form. Turnip necessarily included in the daily menu. Behind the turnip came the radish. In northern Europe, turnips and cabbages were added to almost every dish. In the East - horseradish, in the South - lentils, peas, beans of different varieties. They even baked bread from peas. Stews were usually prepared with peas or beans.

The assortment of medieval garden crops differed from the modern one. In the course were asparagus, budyak, kupena, which were added to the salad; quinoa, potashnik, curly, - mixed in vinaigrette; sorrel, nettle, hogweed - added to the soup. Raw chewed bearberry, knotweed, mint and bison.

Carrots and beets entered the diet only in the 16th century.

The most common fruit crops in the Middle Ages were apple and gooseberries. In fact, until the end of the fifteenth century. the assortment of vegetables and fruits grown in the vegetable gardens and orchards of Europeans did not change significantly compared to the Roman era. But, thanks to the Arabs, the Europeans of the Middle Ages got acquainted with citrus fruits: oranges and lemons. From Egypt came almonds, from the East (after the Crusades) - apricots.

In addition to bread, they ate a lot of cereals. In the North - barley, in the East - rye grout, in the South - semolina. Buckwheat was hardly sown in the Middle Ages. Millet and spelt were very common crops. Millet is the oldest cereal in Europe; millet cakes and millet porridge were made from it. From the unpretentious spelled, which grew almost everywhere and was not afraid of the vagaries of the weather, they made noodles. Corn, potatoes, tomatoes, sunflowers and many other things known today, medieval people did not yet know.

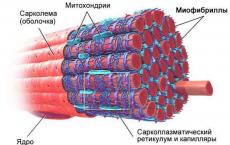

The diet of ordinary townspeople and peasants differed from the modern one by insufficient protein content. About 60% of the diet (if not more in certain low-income groups of the population) was occupied by carbohydrates: bread, flat cakes, various cereals. Insufficient nutritional value of food was compensated by quantity. People only ate when their stomachs were full. And the feeling of satiety, as a rule, was associated with heaviness in the stomach. Meat was consumed relatively rarely, mainly during the holidays. True, the table of noble seigneurs, clergy and urban aristocracy was very plentiful and varied.

There have always been differences in the nutrition of the "tops" and "bottoms" of society. The former were not infringed upon in meat dishes, primarily due to the prevalence of hunting, since in the forests of the medieval West at that time there was still quite a lot of game. There were bears, wolverines, deer, wild boars, roe deer, aurochs, bison, hares; birds - black grouse, partridges, capercaillie, bustards, wild geese, ducks, etc. According to archaeologists, medieval people ate the meat of birds such as cranes, eagles, magpies, rooks, herons, bitterns. Small birds from the order of passerines were considered a delicacy. Chopped starlings and tits diluted vegetable salads. Fried kinglets and shrikes were served cold. Orioles and flycatchers were baked, wagtails were stewed. Swallows and larks were stuffed into pies. The more beautiful the bird was, the more refined the dish was considered from it. For example, nightingale tongue pate was prepared only on major holidays by royal or ducal cooks. At the same time, significantly more animals were exterminated than they could be eaten or stored for future use, and, as a rule, most of the meat of wild animals simply disappeared due to the inability to save it. Therefore, by the end of the Middle Ages, hunting could no longer be relied upon as a sure means of subsistence. Secondly, the table of a noble person could always be replenished at the expense of the city market (the market in Paris was especially famous for its abundance), where you could buy a wide variety of products - from game to fine wines and fruits. In addition to game, the meat of poultry and animals was consumed - pork (a part of the forest was usually fenced off for fattening pigs and wild boars were driven there), lamb, goat meat; goose and chicken meat. The balance of meat and vegetable food depended not only on the geographical, economic and social, but also on the religious conditions of society. As you know, in total, about half of the year (166 days) in the Middle Ages were fast days associated with the four main and weekly (Wednesday, Friday, Saturday) fasts. These days, with more or less severity, it was forbidden to eat meat and meat and dairy products. Exceptions were made only for seriously ill patients, women in childbirth, Jews. In the Mediterranean region, meat was consumed less than in Northern Europe. It was probably the hot climate of the Mediterranean. But not only him. Due to the traditional lack of fodder, grazing, etc. there were fewer livestock. The highest consumption in Europe during the late Middle Ages was the consumption of meat in Hungary: an average of about 80 kg per year. In Italy, in Florence, for example, about 50 kg. In Siena 30 kg in the 15th century. People in Central and Eastern Europe ate more beef and pork. In England, Spain, Southern France and Italy - lamb. Pigeons were bred especially for food. The townspeople ate more meat than the peasants. Of all the types of food consumed then, it was mainly pork that was easily digested, the rest of the products often contributed to indigestion. Probably for this reason, the type of a fat, puffy person, outwardly rather portly, but in reality simply malnourished and suffering from unhealthy corpulence, became widespread.

Noticeably supplemented and diversified the table of a medieval person (especially during the days of numerous long fasts) fish - fresh (raw or half-cooked fish was eaten mainly in winter, when there was not enough greens and vitamins), but especially smoked, dried, dried or salted (such fish was eaten on the road, just like cakes). For the inhabitants of the sea coast, fish and seafood were almost the main food. The Baltic and the North Sea fed herring, the Atlantic - cod and mackerel, the Mediterranean - tuna and sardines. Away from the sea, the waters of large and small rivers and lakes served as a source of rich fish resources. Fish, to a lesser extent than meat, was the privilege of the rich. But if the food of the poor was cheap local fish, then the rich could afford to feast on "noble" fish brought from afar.

The mass salting of fish for a long time was hindered by the lack of salt, which was a very expensive product in those days. Rock salt was rarely mined, more often salt-containing sources were used: salt water was evaporated in salt pans, and then the salt was pressed into cakes, which were sold at a high price. Sometimes these lumps of salt - of course, this applies primarily to the early Middle Ages - played the role of money. But even later, the housewives took care of every pinch of salt, so it was not easy to salt a lot of fish. The lack of salt was partly compensated by the use of spices - cloves, pepper, cinnamon, laurel, nutmeg, and many others. etc. Pepper and cinnamon were brought from the East, and they were very expensive, since ordinary people could not afford them. The common people more often ate mustard, dill, cumin, onion, and garlic that grew everywhere. The widespread use of spices can be explained not only by the gastronomic tastes of the era, but it was also prestigious. In addition, spices were used to diversify dishes and, if possible, hide the bad smell of meat, fish, poultry, which were difficult to keep fresh in the Middle Ages. And, finally, the abundance of spices, put in sauces and gravies, compensated for the poor processing of products and the roughness of the dishes. At the same time, spices very often changed the initial taste of food and caused a strong burning sensation in the stomach.

In the XI-XIII centuries. medieval man rarely ate dairy products and consumed little fat. The main source of vegetable fat for a long time was flax and hemp (olive oil was common in Greece and the Middle East, it was practically unknown north of the Alps); animal is a pig. It has been noticed that in the south of Europe fats of vegetable origin were more common, in the north - animal fats. Vegetable oil was also made from pistachios, almonds, walnuts and pine nuts, chestnuts and mustard.

From milk, the inhabitants of the mountains (especially in Switzerland) made cheese, the inhabitants of the plains - cottage cheese. Sour milk was used to make curdled milk. Very rarely, milk was used to make sour cream and butter. Animal oil in general was an extraordinary luxury, and was constantly on the table only of kings, emperors, and the highest nobility. For a long time, Europe was limited in sweets, sugar appeared in Europe thanks to the Arabs and up to the 16th century. considered a luxury. It was obtained from sugar cane and was expensive and labor intensive to produce. Therefore, sugar was available only to the wealthy sections of society.

Of course, the provision of food largely depended on the natural, climatic and weather conditions of a particular area. Any whim of nature (drought, heavy rains, early frosts, storms, etc.) brought the peasant economy out of its usual rhythm and could lead to famine, the fear of which Europeans experienced throughout the Middle Ages. Therefore, it is no coincidence that during the Middle Ages many medieval authors constantly talk about the threat of famine. For example, an empty stomach became a recurring theme in the medieval novel about the fox Renard. In the conditions of the Middle Ages, when the threat of hunger always lay in wait for a person, the main advantage of food and the table was satiety and abundance. On a holiday, it was necessary to eat so that on hungry days there was something to remember. Therefore, for a wedding in the village, the family slaughtered the last cattle and cleaned the cellar to the ground. On weekdays, a piece of lard with bread was considered by an English commoner as “royal food”, and some Italian sharecropper limited himself to a loaf of bread with cheese and onions. In general, as F. Braudel points out, during the late Middle Ages, the average mass was limited to 2 thousand calories per day and only the upper strata of society “reached out” to the needs of a modern person (it is defined as 3.5 - 5 thousand calories). They ate in the Middle Ages usually twice a day. A funny saying has survived from those times that angels need food once a day, people twice, and animals three times. They ate at different hours than now. The peasants had breakfast no later than 6 o’clock in the morning (it is no coincidence that the breakfast in German was called “frushtyuk”, i.e. “early piece”, the French name for breakfast “degen” and the Italian name “dijune” (early) are similar in meaning to it.) In the morning they ate most of the daily diet in order to work better. Soup ripened during the day (“supe” in France, “sopper” (soup food) in England, “mittag” (noon) in Germany), and people had lunch. By evening, the work was over - there was no need to eat. As soon as it got dark, the common people of the village and city went to bed. Over time, the nobility imposed its food tradition on the whole society: breakfast approached noon, lunch wedged in the middle of the day, dinner shifted towards evening.

At the end of the 15th century, the first consequences of the Great geographical discoveries began to affect the food of Europeans. After the discovery of the New World, pumpkin, zucchini, Mexican cucumber, sweet potatoes (yam), beans, peppers, cocoa, coffee, as well as corn (maize), potatoes, tomatoes, sunflowers appeared in the diet of Europeans, which were brought by the Spaniards and the British from America at the beginning of the 16th century.

Of the drinks, grape wine traditionally occupied the first place - and not only because the Europeans were happy to indulge in the joys of Bacchus. The consumption of wine was forced by the poor quality of the water, which, as a rule, was not boiled and which, due to the fact that nothing was known about pathogenic microbes, caused stomach diseases. They drank a lot of wine, according to some researchers, up to 1.5 liters per day. Wine was given even to children. Wine was necessary not only for meals, but also for the preparation of medicines. Along with olive oil, it was considered a good solvent. Wine was also used for church needs, during the liturgy, and grape must satisfied the needs of a medieval person for sweets. But if the main part of the population resorted to local wine, often of poor quality, then the upper strata of society ordered fine wines from distant countries. Cypriot, Rhine, Moselle, Tokay wines, and malvasia enjoyed a high reputation in the late Middle Ages. At a later time - port wine, madeira, sherry, malaga. In the south, natural wines were preferred, in the north of Europe, in cooler climates, fortified ones. Over time, they became addicted to vodka and alcohol (they learned how to make alcohol in distillers around 1100, but for a long time the production of alcohol was in the hands of pharmacists, who considered alcohol as a medicine that gives a feeling of “warmth and confidence”), which for a long time belonged to medicines. At the end of the XV century. this "medicine" was to the taste of so many citizens that the Nuremberg authorities were forced to ban the sale of alcohol on holidays. In the fourteenth century Italian liquor appeared, in the same century they learned how to make alcohol from fermented grain.

|

|

| Crush of grapes. Pergola training, 1385 Bologne, Niccolo-student, Forli. | Brewer at work. the housebook of the brother "s endowment of the family Mendel 1425. |

|

|

| Party at the tavern, Flanders 1455 | Good and bad manners. Valerius Maximus, Facta et dicta memorabilia, Bruges 1475 |

A truly popular drink, especially north of the Alps, was beer, which did not refuse to know. The best beer was brewed from germinated barley (malt) with the addition of hops (by the way, the use of hops for brewing was precisely the discovery of the Middle Ages, the first reliable mention of it dates back to the 12th century; in general, barley beer (braga) was known in antiquity) and some kind of cereal. From the twelfth century Beer is mentioned all the time. Barley beer (ale) was especially loved in England, but hop-based brewing only arrived from the continent around 1400. Beer consumption was about the same as wine consumption, i.e. 1.5 liters daily. In northern France, beer competed with cider, which was especially widely used from the end of the 15th century. and enjoyed success mainly with the common people.

From the second half of the sixteenth century chocolate appeared in Europe; in the first half of the seventeenth century. - coffee and tea, incl. they cannot be considered "medieval" drinks.

26 chose

Feast in a medieval castle. Massive oak tables are bursting with a variety of dishes.

The wine flows like water. Gallant knights elegantly look after ladies in expensive outfits, and minstrels delight the ears of the feasting…

Or so: one of the ladies grabs a piece of meat with a not too clean hand, and fat - oh horror! - drips onto the velvet woven with gold. The meat turns out to be tough and so flavored with spices that the taste is almost not felt, and the wine is sour ...

Which of the two pictures seems more believable to you?

There are two opposite points of view on the Middle Ages. For some, this is the darkest and cruelest time in human history. The preachers of this view and the inventors of the very term - "Middle Ages" - were the titans of the Renaissance, who considered this thousand-year period "a fall into darkness" after brilliant antiquity. Readers of historical novels see wise kings, valiant knights, beautiful ladies and free troubadours in the Middle Ages. As a less romantic option, Gothic architecture, the craftsmanship of obscure artisans and artists, and the beginning of the Age of Discovery are offered. As is often the case, the truth is somewhere in the middle...

The same can be said about medieval cuisine. On the one hand, in the first centuries after the fall of the ancient world, the food culture changed not for the better - trade relations disappeared, household methods were simplified, exquisite recipes sunk into oblivion ... And the church, which played a huge role in the new world, did not encourage gourmets ... But on the other hand, people remained people, trying to bring little joys into their lives ... Yes, and ancient recipes were rewritten - and not just anywhere, but precisely in monasteries ... And then progress in the economy was outlined ...

The cuisine of the Middle Ages, of course, was different. How to compare the dishes of sunny Italy and snowy Sweden? Or the coarse but plentiful food of the barbarians who swept Rome off the face of the Earth, and the dishes of the late Middle Ages, which became the prototype of exquisite French, bright Italian and juicy Spanish dishes of our time? And, of course, the food of the poor peasant (if there was any at all - hunger became common in the Middle Ages) was different from what the owner of the castle and his household ate. But still, I will try to offer you a variant of the daily menu several centuries ago.

Let's start, as usual, with breakfast. The familiar principle "Eat breakfast yourself, share lunch with a friend, and give dinner to the enemy" did not work in the Middle Ages. According to church morality, eating early in the morning meant indulging "bodily weaknesses", which was not encouraged. Privileged classes and monks, as a rule, did not have breakfast, and those who had to work all day, bypassed the ban. But still, breakfast was the simplest and consisted of a piece of bread with water or, at best and depending on the region, wine or beer.

Whiter than a daisy beard

She was cold. And not water - Wine washed gray hair in the morning,

When he dipped bread in a bowl for breakfast.

/J. Chaucer. The Canterbury Tales/

In the Middle Ages, they baked a variety of breads: from expensive triple-ground wheat flour to "poor people's bread" from a mixture of different cereals, to which beans, acorns and even hay were added in lean years. In the course were unleavened cakes, yeast bread, products with the addition of spices, lard and onions. Even in castles, bakers didn't work every day, so stale bread was par for the course. By the way, it was often used as plates or bowls.

I bring to your attention an English recipe for gingerbread (the original is given in one of the oldest cookbooks in the British Isles - Form of Cury(1390) The recipe was adapted for you and me by culinary historians, since it was not customary to indicate the number of ingredients and the procedure in the old manuals.

|

"Forme of Cury". 14th century manuscript |

- 1 glass of honey

- 1 loaf wheat bread

- ¾ tablespoon cinnamon

- ¼ tablespoon white pepper

- ¼ tablespoon ground ginger

- A pinch of ground saffron

- Cinnamon and ground sandalwood bark for sprinkling

Bring honey to a boil, reduce heat and simmer for 5-10 minutes, then remove from heat. Remove foam, add pepper, cinnamon, ginger, saffron and pre-crumbled bread. Mix until smooth and form balls from the resulting dough. Roll in a mixture of cinnamon and sandalwood bark. I confess that the use of sandalwood as a spice confuses me a little. I would leave only cinnamon for sprinkling, in which you can add a little ground saffron for color.

In Italy in the Middle Ages, pasta was often prepared, modern recipes of which trace their history back to those times. Even Boccaccio's Decameron mentions it!

And a few drinks for breakfast. As you know, tea and coffee appeared in Europe towards the end of the Middle Ages, so, in addition to water, wine or beer was consumed in those days. In the southern regions, where the traditions of winemaking have not been interrupted since ancient times, wine was the cheapest and most common drink, which was given even to small children. However, historians claim that medieval wines were not of the best quality and would hardly please modern gourmets.

In the northern countries, wine was a delicacy that only wealthy people could consume. Wine, especially heated with honey, spices and herbs, was considered a cure for many diseases and a general tonic. But beer flowed like water here, and the traditions of brewing in England, Germany and the Czech Republic have medieval roots! Remember the old ballad about John Barleycorn about the production of the famous ale?

So let it be until the end of time

The bottom does not dry out

In the barrel where John bubbles

Barley Grain!

/R. Burns translated by S. Ya. Marshak/

People of the Middle Ages (as, indeed, some of our contemporaries) believed that milk was not suitable for healthy adults, it was given only to children, the elderly and the sick. In addition, it was poorly stored, so almond milk was more often used, which could be consumed during fasting and prepared desserts based on it.

An early 15th century French recipe (the Burgundian cookbook "Du fait de cuisine") of the century is extremely simple:

Take 2 cups of chopped almonds, add 3 cups of hot water, mix well and infuse for 10-15 minutes, continuing to stir. Rub through a fine sieve, trying to achieve maximum uniformity. Honey, vanilla and other spices can be added to milk.

Shall we go to lunch? The people of the Middle Ages dined, as expected, in the middle of the day, and the specific time depended on the class and circumstances. The daily meal was also quite light, that is, people ate most of all for dinner, trying to get enough for the day ahead. The modern principle "do not eat after 18.00" was clearly not in honor ... Although, as a rule, people of the Middle Ages did not suffer from overweight, and the apparent fullness of some turned out to be puffiness from malnutrition.

For lunch, they ate bread, fresh and boiled vegetables (cabbage, onions and turnips were popular), seasonal fruits, eggs, cheese, very rarely meat or fish. In monastic refectories, a thick soup or stew of vegetables and herbs was often served, to which bread or a piece of pie was supposed to be served.

|

Vegetables and fruits on medieval miniatures, XIV-XV centuries. |

Let's try to cook a cabbage dish according to a German recipe (Bavaria, early 15th century)

For 1 kg of cooked cabbage (meaning boiled or stewed) we need:

- 4 tablespoons mustard

- 2 tablespoons honey

- 2 glasses of white wine

- 2 tablespoons cumin

- 1 tablespoon anise seeds

Squeeze the cabbage, add all the ingredients, mix, let it brew.

I would prefer to cook a similar dish with fresh cabbage, although as a side dish for German sausages or sausages, which appeared precisely in the Middle Ages, and this is suitable.

|

Collection of cabbage. Miniature from an old herbalist |

Bread during lunch was often replaced with pies. They were cooked open and closed, with meat, poultry, fresh or salted fish, vegetables, mushrooms, cheese or fruit. It is interesting that in the old recipes no attention is paid to the dough at all, only the fillings are described - probably every culinary specialist already knew how to make it!

I was interested in a French recipe for parsnip pie, for which it is quite possible to use ready-made puff pastry. The recipe dates back to the 15th-16th centuries, and the ingredients of the filling may seem poorly combined with each other to a modern person.

So we will need:

- 200 g chopped parsnips

- ½ cup chopped mint

- 2 eggs

- ½ cup shredded hard cheese

- 4 tablespoons butter

- 1 tablespoon sugar

- 2 tablespoons blackcurrants (very unexpected, right?)

- Cinnamon, grated nutmeg

Mix all the ingredients, put on the dough and bake for about 30 minutes over medium heat.

The recipe was tested in practice - the taste is completely unusual, but very interesting! "Plays" just blackcurrant in combination with mint and spices.

And finally, the main meal of the day - dinner. It was customary for the whole family to gather at dinner (a wonderful tradition after all!), And the noble and rich invited relatives and friends. Everything that was in the house was exhibited for dinner - of course, taking into account the possibilities of the family. Eating alone was not welcome - it was believed that it was more difficult to indulge gluttony in public, since table conversation distracts from food and drinks.

In the early Middle Ages, etiquette was very simple - everyone ate as he liked, using only a knife, a spoon and his own hands. Over time, decent behavior at the table was welcomed and testified to a good upbringing.

The abbess in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales was clearly familiar with the rules of etiquette:

She kept herself dignified at the table:

Do not choke on strong liquor,

Slightly dipping your fingers in the gravy,

He will not wipe them on his sleeve or collar.

Not a speck around her device.

She wiped her lips so often

That there was no trace of fat on the goblet.

Waiting your turn with dignity

I chose a piece without greed.

It was a pleasure to sit next to her -

She was so polite and so kind.

At first, all dishes were served at the same time - meat and fish were side by side with sweets and pies for many hours of feast, gradually cooling down. The custom of "changing dishes" arose already closer to the New Age. Much attention was paid to table decoration - some dishes were intended only for this. For example, no one ate beautiful sugar castles and swans, they only admired them. And sometimes they were even made of plaster! For decoration, peacocks or swans were used, presented by cooks in their "natural form", with feathers stuck in. However, the meat of these birds was highly valued, but because of the rarity, not the taste.

However, ordinary pies looked very beautiful.

|

Pies designed in the 16th-17th centuries |

Let's return to other dishes of the medieval dinner, the main of which were meat and fish. Fish in the Middle Ages ate a lot. The Nordic countries supplied all of Europe with salted herring and dried cod (in Portugal, for example, imported cod is still extremely popular, from which national dishes are prepared). In coastal areas, fishing played an important role, fish were caught in rivers and lakes - fortunately, the environment allowed! In monasteries and castle farms, fish were specially bred, carps were especially popular.

|

Medieval miniature. Norway, 16th century |

As a rule, the fish was baked in pies, and also served boiled or stewed, poured with spicy sweet and sour sauces of honey, vinegar and spices. Judging by the descriptions, medieval sauces would not really appeal to a modern person, they did not emphasize the taste of the dish, but completely overshadowed it. "And woe to the cook if the sauce is bland," said Chaucer in The Canterbury Tales.

The same can be said about the use of spices - from our point of view, it would be more correct to call it abuse. And the point is not that, as they used to think, spices drowned out the taste of stale foods. Spices were expensive, and those who could afford foreign cinnamon and cloves did not buy rotten meat. It was a matter of prestige and status, and the taste of dishes for the rich had to be fundamentally different from "simple food".

The real king of medieval feasts was meat, and its use was also a sign of social status and wealth. Modern doctors believe that such a disease as gout, very common among the "powerful world" of the Middle Ages, was caused by the immoderate consumption of animal protein. The banquet tables were literally bursting with heavy and fatty meat dishes flavored with a huge amount of spices.

However, whole roasted carcasses of bulls and big game were not cooked as often as novelists like to describe. "Historical reenactors" claim that the dish is unevenly fried - burnt on the outside and half-baked inside. More often cooked stew or boiled meat, as well as a variety of meatballs and sausages.

I will illustrate my words with an old recipe (XV century), equally popular on both sides of the English Channel. To prepare beef stew in Old French or Old English, we need:

- 1 kg meat

- Spices and herbs: cinnamon and sage (1/2 teaspoon each), ground cloves, allspice and black pepper, nutmeg (1/4 teaspoon each), 1 chopped onion, a tablespoon of chopped parsley, salt, a pinch of saffron.

- 3 large slices of coarse bread

- Wine vinegar (1/4 cup)

Cut the beef into small pieces, put in a saucepan and add water to cover the meat. Bring to a boil, reduce heat and simmer for 20 minutes. Strain the broth, add spices and herbs (except saffron) and simmer the meat until tender. Sliced bread pour vinegar so that it is completely soaked, chop. When the meat is ready, add bread and saffron, mix.

In fairness, it must be said that meat was not always present on the menu of a medieval person. According to the church calendar, it could not be eaten for about 150 days a year - on Wednesdays, Fridays, Saturdays and during fasts, and the Benedictine monks were not allowed to eat "meat of four-legged animals" at all according to the charter of the Order. But people tend to look for loopholes in the laws - so, over time, the meat of waterfowl and sea birds, as well as animals living in the water, was equated with fish. According to these rules, the beaver was considered a fish!

|

French miniature, 1480 |

".. I really want to eat this chicken and at the same time not sin. Listen, my brother, do me a favor - ... sprinkle it with a few drops of water and call it a carp" - remember this scene from "Countess de Monsoro"? Or another, from the "Chronicles of the Reign of Charles IX": "To everyone's amazement, the old Franciscan went for water, sprinkled the chickens' heads and read something like a prayer in an indistinct patter. It ended with the words:" I call you Trout, and you Macrelia "? These are not the fantasies of Dumas and Mérimée, such stories are often found in medieval literature!

Meat was not available to the poorest segments of the population, the poor townspeople did not eat it for years, and the peasant could rarely eat pork or chicken. And ordinary people were forbidden to hunt under pain of death - game in the forests was considered royal, count or baronial. Remember the stories of the valiant Robin Hood of Sherwood Forest? His enemy, the Sheriff of Nottingham, was just pursuing poachers who dared to hunt in the royal forest ...

The French king Henry IV of Navarre said: "If God gives me a little more time, every peasant will have a chicken in a pot on Sundays." Growing up at a poor Gascon court, Henry saw well how ordinary people live, and he also had unrefined tastes. Chicken according to the recipe of the "good king" is still cooked in France, this dish is especially popular in Chartres, where the future monarch was crowned.

For cooking we need:

- Large chicken with giblets

- Chicken gizzards and liver optional

- 200 grams of bacon

- 2 onions

- 1 egg and 1 yolk

- 4 garlic cloves

- 200 g dried bread

- 2 medium turnips

- 3-4 carrots

- 2-3 leeks

- 1 parsnip

- Celery, parsley, bay leaf, cloves, salt, pepper

Chop offal, bacon, onion, garlic and parsley. Soak bread in milk and squeeze. Mix everything, add raw eggs, salt, pepper, stuff the chicken and sew it up. Boil the chicken, completely covered with water, for about 1 hour, skimming off the foam. Cut the remaining vegetables into large pieces, put in a saucepan, add spices and cook for another 1.5 hours. The dish is served as follows: broth is poured into plates with croutons and a little minced meat is put. Chicken and vegetables are served separately. A simple but satisfying lunch for a large family, and not just for one day!

Finishing a brief excursion into the history of medieval cuisine, I want to say that nothing ever stopped a person in an effort to eat delicious food. As one of Chaucer's characters stated: "Happy is only the one who, enjoying, lives cheerfully," and this meant, among other things, food! Yes, in those days there was no abundance and variety of products that we have now ... Yes, they have not yet come up with those gourmet dishes that we admire today ... Yes, enjoying food was not encouraged ...

But still, the distant ancestors of modern Europeans tried very hard, and many dishes of the Middle Ages seem interesting to me, although unusual. And you?

Svetlana Vetka , specially for Etoya.ru