Who in Rus' is the best to live. Nekrasov to whom in Rus' to live well. The spiritual needs of man are indestructible

Plot lines and their correlation in N. A. Nekrasov's poem "Who should live well in Rus'"

The plot is the development of the action, the course of events that can follow each other in a work in chronological order (fairy tales, chivalric novels) or grouped in such a way as to help identify its main idea, the main conflict (concentric plot). The plot reflects the life contradictions, clashes and relationships of the characters, the evolution of their characters and behavior.

The plot of “Who should live well in Rus'” is largely due to the genre of the epic poem, which reproduces all the diversity of the life of the people in the post-reform period: their hopes and dramas, holidays and everyday life, episodes and destinies, legends and facts, confessions and rumors, doubts and insights, defeats and overcomings, illusions and reality, past and present. And in this polyphony of folk life, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish the voice of the author, who invited the reader to accept the terms of the game and go on an exciting journey with his heroes. The author himself strictly follows the rules of this game, playing the role of a conscientious narrator and imperceptibly directing its course, in general, practically without revealing his adulthood. Only sometimes does he allow himself to discover his true level. This role of the author is due to the intended purpose of the poem - not only to trace the growth of peasant self-consciousness in the post-reform period, but equally to contribute to this process. After all, likening the soul of the people to unplowed virgin soil and calling on the sower, the poet could not help but feel like one of them.

The storyline of the poem - the wanderings of seven temporarily obligated men across the vast expanses of Rus' in search of a happy one - is designed to accomplish this task.

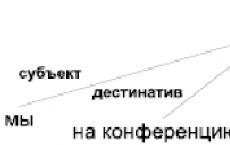

The plot “Who should live well in Rus'” (a necessary element of the plot) is a dispute about the happiness of seven men from adjacent villages with symbolic names (Zaplatovo, Dyryavino, Razutovo, Znobishino, Gorelovo, Neyolovo, Neurozhayka). They go in search of a happy one, having received the support of a grateful magical bird. The role of wanderers in the development of the plot is significant and responsible. Their images are devoid of individual outline, as is customary in folklore. We only know their names and passions. So, Roman considers the landowner a happy man, Demyan - an official, Luka - a priest. Ivan and Metrodor Gubin believe that the "fat-bellied merchant" lives freely in Rus', the old man Pakhom - that of a minister, and Prov - that of a tsar.

The Great Reform changed many things in the life of the peasants, but for the most part they were not ready for it. Their concepts weighed down the age-old traditions of slavery, and consciousness was just beginning to awaken, as evidenced by the dispute between the peasants in the poem.

Nekrasov understood very well that the happiness of the people largely depends on how much he will be able to realize his place in life. It is curious that the initial plot outlined in the dispute turns out to be false: of the alleged “lucky ones”, the peasants talk only with the priest and the landowner, refusing other meetings. The fact is that at this stage the possibility of muzhik happiness does not even enter their heads. Yes, and this very concept is associated with them only with the absence of what every hour makes them, the peasants, unhappy - hunger, exhausting work, dependence on all sorts of masters.

That is why at the beginning

Beggars, soldiers

Strangers didn't ask

How is it easy for them, is it difficult

Lives in Rus'?

In the poem "Who Lives Well in Rus'", in addition to the main plot, which solves the problem of the growth of peasant self-consciousness, there are numerous side storylines. Each of them contributes something significant to the consciousness of the peasants.

The turning point in the development of events in the poem is the meeting of the seven fortune-seekers with the village priest.

The clergy, especially the rural ones, were closer to the common people in the nature of their activities than other ruling classes. Ceremonies associated with the birth of children, weddings, funerals were performed by priests. They possessed the secrets of simple peasant sins and genuine tragedies. Naturally, the best among them could not help but sympathize with the common people, instilling in them love for their neighbor, meekness, patience and faith. It was with such a priest that the men met. He helped them, firstly, to translate their vague ideas of happiness into a clear formula of “peace, wealth, honor”, and secondly, he revealed to them a world of suffering that was not associated with hard work, painful hunger or humiliation. The priest, in essence, translates the concept of happiness into a moral category for the peasants.

The rebuke to Luke, who is called a foolish narrator, is distinguished by rare unanimity and anger:

What did you take? stubborn head!

Rustic club!

There, climb into the dispute!

Bell Nobles -

Priests live like princes.

For the first time, the peasants could think that if a well-fed and free priest suffers like that, then it is possible that a hungry and dependent peasant can be happy. And shouldn't it be more thorough to find out what happiness is before traveling around Rus' in search of a happy one? This is how seven men find themselves at the "country fair" in the rich village of Kuzminsky, with two old churches, with a tightly packed school and

A paramedic's hut with a frightening sign, most importantly, with numerous drinking establishments. The fair polyphony is filled with light, jubilant intonations. The narrator rejoices at the abundance of products of rural masters, the variety of fruits of overwork, unpretentious entertainment, with an experienced hand he makes sketches of peasant characters, types, genre scenes, but sometimes he suddenly seems to forget about his role as a modest narrator, and the mighty figure of the poet-educator stands in front of the readers in full growth :

Eh! Eh! will the time come

When (come desired! ..)

Let the peasant understand

What is a portrait of a portrait,

What is a book a book?

When a man is not Blucher

And not my lord foolish -

Belinsky and Gogol

Will you carry it from the market?

Seven peasants have the opportunity to see how the irresistible people's energy, strength, joy are absorbed by ugly drunkenness. So, maybe it is the cause of misfortunes, and if people get rid of cravings for wine, life will change? They cannot help thinking about this when they encounter Yakim Nagim. The episode with the plowman is of great importance in the formation and development of the peasant identity. Nekrasov endows a simple grain grower with an understanding of the significance of public opinion: Yakim Nagoi snatches a pencil from the hands of the intellectual Pavlusha Veretennikov, who is ready to write down in a book that smart Russian peasants are being destroyed by vodka. He confidently states:

To the master's measure

Don't kill the peasant!

Yakim Nagoi easily establishes causal relationships. It is not vodka that makes the life of a peasant unbearable, but an unbearable life that makes them turn to vodka as their only consolation. He understands well who appropriates the fruits of peasant labor:

You work alone

And a little work is over,

Look, there are three equity holders:

God, king and lord!

The peasants, who previously thoughtlessly agreed with Pavlusha Veretennikov, suddenly agree with Yakim:

Work would not fail

Trouble would not prevail

Hops will not overcome us!

Wanderers after this meeting have the opportunity to realize the class difference in the concept of happiness and hostility to the people of the ruling classes. Now they are thinking more and more about the fate of the peasants and are trying to find

Among them are happy, or rather, it is important for them to identify popular ideas about happiness, to compare them with their own.

“Hey, the happiness of the peasant!

Leaky with patches

Humpbacked with corns,

Get off home!" -

Here is the final opinion of the wanderers about the "muzhik's happiness."

The story of Ermil Girin is an insert episode with an independent plot. The peasant Fedosey from the village of Dymoglotovo tells her happiness-seekers, not without reason deciding that this “just a peasant” can be called happy. He had everything: "calmness, and money, and honor." A literate man, he was first a clerk under the manager and in this position he managed to win the respect and appreciation of his fellow villagers, helping them in difficult paperwork for them free of charge. Then, under the young prince, he was elected steward.

Yermilo went to reign

Over the whole prince's patrimony,

And he reigned!

At seven years of a worldly penny

Didn't squeeze under the nail

At the age of seven, he did not touch the right one,

Didn't let the guilty

I didn’t bend my heart…

However, the "gray-haired priest" recalled Yermila's "sin" when, instead of his brother Mitriy, he recruited the son of the widow Nenila Vlasyevna. Ermila was tormented by his conscience, he almost committed suicide until he corrected his deed. After this incident, Ermil Girin resigned from the post of headman and acquired a mill, and moreover, no money happened to him when he traded it, and the world helped him to shame the merchant Altynnikov:

Cunning, strong clerks,

And their world is stronger

The merchant Altynnikov is rich,

And he can't resist

Against the worldly treasury...

Girin returned the money and since then has become “more than ever before all the people love” for truth, intelligence and kindness. The author left the seven wanderers to draw many lessons from this story. They could rise to an understanding of the highest happiness, which consisted in serving their class brothers, the people. Peasants

They could think about the fact that only in unity they represent an invincible force. Finally, they should have come to understand that for happiness a person needs to have a clear conscience. However, when the peasants were about to visit Yermil, it turned out that “he is sitting in prison,” because, apparently, he did not want to take the side of the bosses, the offenders of the people. The end of the story of Ermil Girin, the author deliberately does not finish, but he is also instructive. The wandering heroes could understand that for such an impeccable reputation, for such a rare happiness, the unknown peasant Girin had to pay with freedom.

On their long journey, wanderers had to think and learn, as well as readers, however.

They were much more prepared for the meeting with the landowner than for the meeting with the priest. The peasants are ironic and mocking both when the landowner boasts of his genealogical tree, and when he speaks of spiritual kinship with the peasant patrimony. They are well aware of the polarity of their own and the landowners' interests. Perhaps for the first time, the wanderers realized that the abolition of serfdom was a great event that forever left in the past the horrors of landlord arbitrariness and omnipotence. And although the reform, which hit "one end on the master, the other on the peasant", completely deprived them of the "lordly caress", but also called for independence, responsibility for arranging their own lives.

In Nekrasov, the theme of women's fate takes place in his work as an independent, especially significant theme. The poet was well aware that in serf Russia, a woman carried a double oppression, social and family. He makes his wanderers think about the fate of a woman, the ancestor of life, the support and guardian of the family - the basis of people's happiness.

Matryona Timofeevna Korchagina was called lucky by her neighbors. In some ways she was really lucky: she was born and raised in a non-drinking family, married for love, but otherwise went the usual path of a peasant woman. From the age of five she began to work, got married early and drank plenty of grievances, insults, hysterical labor in her husband's family, lost her first-born son and remained a soldier with children. Matryona Timofeevna is familiar with the master's rods and beatings of her husband. Hardworking, talented (“And a kind worker, / And a hunter to sing and dance / I was from a young age”), passionately loving children, family, Matrena Timofeevna did not break under the blows of fate. In lawlessness and humiliation, she found the strength to fight injustice and won, returning her husband from the soldiery. Matrena Timofeevna is the embodiment of the moral strength, intelligence and patience of a Russian woman, selflessness and beauty.

In the bitter hopelessness of the peasant fate, the people, almost by folklore inertia, associated happiness with good luck (Matryona Timofeevna, for example, was helped by the governor), but by this time the wanderers had already seen something and did not believe in a lucky break, so they asked Matryona Timofeevna to lay out their whole soul . And it's hard for them to disagree with her words:

Keys to female happiness

From our free will

abandoned, lost

God himself!

However, the conversation with Matrena Timofeevna turned out to be very important for the seven peasants in determining the paths, roads to the happiness of the people. A large role in this was played by an insert episode with an independent plot about Saveliy, the Holy Russian hero.

Savely grew up in a remote village, separated from the city by dense forests and swamps. The Korezsky peasants were distinguished by their independent disposition, and the landowner Shalashnikov had “not so hot great incomes” from them, although he fought the peasants desperately:

Weak people gave up

And the strong for the patrimony

They stood well.

The manager Vogel, sent by Shalashnikov, tricked the Korean peasants into making a road, and then finally enslaved them:

The German has a dead grip:

Until they let the world go

Without moving away, sucks.

The men did not tolerate violence - they executed the German Vogel by burying him alive in the ground. The seven wanderers are confronted with a difficult question: is violence against oppressors justified? To make it easier for them to answer it, the poet introduces another tragic episode into the plot - the death of the first-born Matryona Timofeevna Demushka, who was killed by pigs due to Savely's oversight. Here the repentance of the old man knows no bounds, he prays, asks for forgiveness from God, goes to the monastery for repentance. The author deliberately emphasizes Savely's religiosity, his compassion for all living things - every flower, every living being. There is a difference in his guilt for the murder of the German Vogel and Demushka. But Savely ultimately does not justify himself and for the murder of the manager, or rather, considers it senseless. It was followed by hard labor, settlement, awareness of wasted power. Savely understands well the hardship of a peasant's life and the righteousness of his anger. He also knows the measure of the potential strength of the "man-hero". However, his conclusion is clear. He says to Matryona Timofeevna:

Be patient, you bastard!

Be patient long-suffering!

We can't find the truth.

The author brings the seven wanderers to the idea of the righteousness of the violent reprisal against the oppressor, and warns against the thoughtlessness of the impulse, which will inevitably be followed by both punishment and repentance, because nothing will change in life from such a single justice.

Wanderers grew wiser during the months of wandering, and the initial thought of a happily living in Rus' was replaced by the thought of people's happiness.

To the elder Vlas from the chapter "Last Child" they talk about the purpose of their journey:

We are looking for, Uncle Vlas,

unworn province,

Not gutted volost,

Surplus village!..

Wanderers think about the universality of happiness (from the province to the village) and mean by it personal inviolability, legal security of property, well-being.

The level of self-awareness of the peasants at this stage is quite high, and now we are talking about ways-incomes to people's happiness. The first obstacle to it in the post-reform years were the remnants of serfdom in the minds of both landowners and peasants. This is discussed in the chapter "Last Child". Here the wanderers get acquainted with the emasculated prince Utyatin, who does not want to recognize the tsarist reform, because his noble arrogance suffers. In order to please the heirs, who were afraid for their inheritance, the peasants, for the promised “poem meadows,” play the “gum” of the former order in front of the landowner. The author does not spare satirical colors, showing their cruel absurdity and obsolescence. But not all peasants agree to submit to the insulting condition of the game. For example, steward Vlas does not want to be a “pea jester”. The plot with Agap Petrov shows that even the most ignorant peasant awakens a sense of dignity - a direct consequence of the reform that cannot be reversed.

The death of the Afterlife is symbolic: it testifies to the final triumph of a new life.

In the final chapter of the poem "A Feast for the Whole World" there are several storylines that take place in numerous songs and legends. One of the main themes raised in them is the theme of sin. The guilt of the ruling classes before the peasants is endless. The song, called "Merry", speaks of the arbitrariness of landowners, officials, even the king, depriving the peasants of their property, destroying their families. “It is glorious to live for the people / Saint in Rus'!” - the refrain of the song, sounding bitter mockery.

Uncombed, “twisted, twisted, cut, tormented” Kalinushka is a typical corvée peasant whose life is written “on his own back”. Growing up "under the snout of the landowner", the corvee peasants especially suffered from their painstaking arbitrariness and stupid prohibitions, for example, the ban on rude words:

We got drunk! really

We celebrated the will

Like a holiday: they cursed so much,

That pop Ivan was offended

For the ringing of bells

Buzzing that day.

The story of the former traveling footman Vikenty Aleksandrovich “About the exemplary serf - Jacob the faithful” is another evidence of the inexorable sin of the autocratic landowner. Mr. Polivanov, with a dark past (“he bought a village with bribes”) and the present (“he went free, drank, drank bitter”), was distinguished by rare cruelty not only in relation to serfs, but even to relatives (“Having married a daughter, a noble husband / Whipped - both drove away naked"). And, of course, he did not spare the “exemplary lackey, faithful Jacob,” whom he “simply blew with his heel” in the teeth.

Jacob is also a product of serfdom, which turned the best moral qualities of the people: fidelity to duty, devotion, selflessness, honesty, diligence - into senseless servility.

Yakov remained devoted to his master, even when he lost his former strength, became decapitated. The landowner seemed to finally appreciate the devotion of the servant, began to call him "friend and brother"! The author invisibly stands behind the narrator, who is called upon to convince the listeners that brotherly relations between master and serf are impossible. Mr. Polivanov forbids his beloved nephew Yakov to marry Arisha, and his uncle's requests do not help. Seeing an opponent in Grisha, the master gives him up as a soldier. Perhaps for the first time, Yakov thought about something, but he managed to tell the master about his wine in only one way - he hung himself over him in the forest.

The theme of sin is vigorously discussed by the feasters. There are as many sinners as there are lucky ones. Here are the landlords, and the tavern-keepers, and the robbers, and the peasants. And the disputes, as in the beginning of the poem, end in a brawl until Iona Lyapushkin, who often visits the Vakhlat side, comes forward with his story.

The author dedicates a special chapter to wanderers and pilgrims who "do not reap, do not sow - feed" throughout Rus'. The narrator does not hide the fact that among them there are many deceivers, hypocrites and even criminals, but there are also true bearers of spirituality, the need for which is so great among the Russian people. She was not destroyed by overwork, nor long slavery, nor even a tavern. The author draws an unpretentious genre scene depicting a family at work in the evening, while the wanderer welcomed by her finishes the "truth of Athos". There is so much trusting attention, warm sympathy, intense fascination on the faces of old people, women, children, that the poet exclaims with tenderness, love and faith:

More Russian people

No limits set:

Before him is a wide path ...

In the mouth of God's pilgrim Jonah, ardently revered by the peasants, the narrator puts the legend "About two great sinners", which he heard in Solovki from Father Pitirim. It is very important for solving the problem of "sin" posed in the poem.

The ataman of the gang of robbers Kudeyar, the murderer, who shed a lot of blood, suddenly repented. To atone for sins, the Lord commanded him to cut down a mighty oak tree with the knife with which he robbed.

Cuts tough wood

Singing glory to the Lord

Years go - moves on

Slowly business forward.

Pan Glukhovsky, the first in that direction, laughed at Kudeyar:

You have to live, old man, in my opinion:

How many slaves I destroy

I torture, I torture, and I hang,

And I would like to see how I sleep.

In a furious rage, the hermit kills Glukhovsky - and a miracle happens:

The tree collapsed, rolled down

From a monk the burden of sins! ..

The seven wanderers had already heard once about Savely, who had committed the sin of murder, and had the opportunity to distinguish the murder of the tormentor Vogel from the accidental death of the infant Demushka. Now they had to understand the difference in the sinfulness of the repentant robber Kudeyar and the convinced executioner and debaucher Glukhovsky, who tortured the peasants. Kudeyar, who executed Pan Glukhovsky, not only did not commit a sin, but was forgiven by God for past sins. This is a new level in the minds of happiness-seekers: they are aware of the possibility of violent actions against the militant executioners of the people - actions that are not opposed to the Christian worldview. "Great noble sin!" - this is the unanimous conclusion of the peasants. But unexpectedly, the sin of the nobility does not exhaust the question of the perpetrators of peasant suffering.

Ignatiy Prokhorov tells a folk ballad about the "widower ammiral" who released eight thousand souls into freedom after his death. The headman Gleb sold the “free” to the heir of the admiral.

God forgives everything, but Judas sin

Doesn't forgive.

Oh man! man! you are the worst of all

And for that you always toil!

The poet was well aware that serfdom not only unleashed the most cruel instincts of the landowners, but disfigured the peasant souls.

The betrayal of fellow peasants is a crime for which there is no forgiveness. And this lesson is learned by our wanderers, who, moreover, had the opportunity to soon be convinced of its effectiveness. Vakhlaks unanimously pounce on Yegorka Shutov, having received an order from the village of Tiskov "to beat him." “If the whole world ordered: / Beat - it’s become, there is something for it,” the headman Vlas says to the wanderers.

Grisha Dobrosklonov sums up the peasant dispute, explaining to the peasants the main reason for the sins of nobles and peasants:

The snake will give birth to kites,

And fasten - the sins of the landowner,

The sin of Jacob, the unfortunate one,

Sin gave birth to Gleb,

Everyone needs to understand, he says, that if “there is no support”, then these sins will no longer exist, that a new time has come.

In the poem “To whom it is good to live in Rus'”, Nekrasov does not bypass the fate of the soldiers - yesterday's peasants, cut off from the land, from families thrown under bullets and rods, often crippled and forgotten. Such is the tall and extremely skinny soldier Ovsyannikov, on whom hung, as on a pole, "a frock coat with medals." Legless and wounded, he still dreams of receiving a “pension” from the state, but not getting him to St. Petersburg: the iron is expensive. At first, “grandfather was fed by the district committee,” and when the instrument deteriorated, he bought three yellow spoons and began to play them, composing a song for simple music:

Toshen light,

There is no truth

Life is boring

The pain is strong.

The episode about the soldier, the hero of Sevastopol, forced to beg (“Nutka, with Georgy - peace, peace”) is instructive for wanderers and the reader, like all the numerous episodes with independent plots included in the poem.

In the difficult search for ways to peasant happiness, it is necessary for the whole world to show mercy and compassion to the undeservedly destitute and offended by fate.

By order of the headman Vlas, Klim, who had outstanding acting skills, helps the soldier Ovsyannikov receive modest public assistance, spectacularly and convincingly retelling his story to the assembled people. A penny, a penny, money poured into the old soldier's wooden plate.

The new "good time" brings new heroes to the stage, next to whom are seven happiness seekers.

The true hero of the final plot of the poem is Grisha Dobrosklonov. From childhood he knew bitter need. His father, the parish deacon Tryphon, lived "poorer than the last rundown peasant", his mother, the "unrequited laborer" Domna, died early. In the seminary, where Grisha studied with his elder brother Savva, it was "dark, cold, gloomy, strict, hungry." Vakhlaks fed kind and simple guys, who paid them for this with work, handled their affairs in the city.

Grateful "love for all Vakhlachin" makes smart Grisha think about their fate.

... And fifteen years

Gregory already knew for sure

What will live for happiness

Wretched and dark

native corner.

This is Gregory explaining to the Vahlaks that serfdom is the cause of all the sins of the nobility and peasants and that it is forever a thing of the past.

All closer, all the more joyful

Listened to Grisha Prov:

grinned, comrades

"Move on your mustache!"

Prov is one of the seven wanderers, who claimed that the tsar lives best in Rus'.

So the final plot is connected with the main one. Thanks to Grisha's explanations, the wanderers realize the root of evil in Russian life and the meaning of will for the peasants.

Vakhlaks appreciate Grisha's extraordinary mind, they respectfully speak of his intention to go "to Moscow, to the new city".

Grisha carefully studies the life, work, cares and aspirations of peasants, artisans, barge haulers, clergy and "all mysterious Rus'."

The angel of mercy - a fabulous image-symbol that replaced the demon of rage - now hovers over Russia. In his song about two paths, sung over a Russian youth, there is a call to go not the usual torn road for the crowd, - the road full of passions, enmity and sin, but the narrow and difficult road for the chosen and strong souls.

Go to the downtrodden

Go to the offended -

Fate prepared for him

The path is glorious, the name is loud

people's protector,

Consumption and Siberia.

Grisha is a talented poet. It is curious that the song “Veselaya”, apparently composed by him, is called “not folk” by the author: priests and courtyards sang it on holidays, and Vakhlaks only stomped and whistled. The signs of bookishness are obvious in it: the strict logic of constructing verses, the generalized irony of the refrain, the vocabulary:

It's nice to live people

Saint in Rus'!

Wanderers listen to this song, and the other two songs of the poet-citizen remain unheard by them.

The first is riddled with pain for the slave past of the Motherland and hope for happy changes:

Enough! Finished with the last calculation,

Done with sir!

The Russian people gather with strength

And learn to be a citizen.

The concept of citizenship is not yet familiar to wanderers, they still have a lot to understand in life, a lot to learn. Perhaps that is why the author at this stage does not connect them with Grisha - on the contrary, he breeds them. The second song by Grisha, where he speaks of the great contradictions of Rus', is still inaccessible to the understanding of the wanderers, but expresses hope for the awakening of the people's forces, for their readiness to fight:

Rat rises -

Innumerable!

The strength will affect her

Invincible!

Grisha Dobrosklonov experiences joyful satisfaction from life, because a simple and noble goal is clearly indicated for him - the struggle for the happiness of the people.

Would our wanderers be under their native roof,

If they could know what was going on with Grisha - here

Folklore traditions in the poem by N.A. Nekrasov "Who should live well in Rus'"

N.A. Nekrasov conceived the poem “Who in Rus' should live well as a“ folk book ”. The poet always made sure that his works had "a style appropriate to the theme." The desire to make the poem as accessible as possible to the peasant reader forced the poet to turn to folklore.

Already from the first pages he is greeted by a fairy tale - a genre beloved by the people: a warbler, grateful for the rescued chick, gives the peasants a “self-assembled tablecloth” and takes care of them throughout the journey.

The reader is familiar with the fabulous beginning of the poem:

In what year - count

What year, guess...

And doubly desirable and familiar are the lines promising the fulfillment of the cherished:

At your request

At my command...

The poet uses fairy tale repetitions in the poem. Such, for example, are appeals to the self-assembly tablecloth or a stable characteristic of the peasants, as well as the reason for their dispute. Fairy-tale tricks literally permeate the entire work of Nekrasov, creating a magical atmosphere where space and time are subordinate to the heroes:

Whether they walked for a long time, or for a short time,

Were they close, were they far...

Widely used in the poem are the techniques of the epic epic. The poet likens many images of peasants to real heroes. Such, for example, is Savely, the Holy Russian hero. Yes, and Savely himself refers to the peasants as genuine heroes:

Do you think, Matryonushka,

The man is not a hero?

And life is not for him,

And death is not written for him

In battle - a hero!

“The peasant horde” in epic tones is drawn by Yakim Nagoi. The bricklayer Trofim, who lifted “at least fourteen pounds” of bricks to the second floor, or the stonemason-Olonchanin, look like real heroes. In the songs of Grisha Dobrosklonov, the vocabulary of the epic epic is used (“The army rises - innumerable!”).

The whole poem is sustained in a fairy tale-colloquial style, where, naturally, there are a lot of phraseological units: “he scattered with his mind”, “almost thirty miles”, “soul hurts”, “dissolved the lyas”, “where did the agility come from”, “suddenly took off, as if by hand ”, “the world is not without good people”, “we will treat you to glory”, “but the thing turned out to be rubbish”, etc.

There are many proverbs and sayings of all kinds in the poem, organically subordinated to poetic rhythms: “Yes, the belly is not a mirror”, “working

the horse eats straw, and the idle dance - oats", "proud pig: scratched on the master's porch", "do not spit on the red-hot iron - it will hiss", "God is high, the king is far", "praise the grass in a haystack, and the master in the coffin", “one is not a bird mill, which, no matter how it flaps its wings, probably won’t fly”, “no matter how much you suffer from work, you won’t be rich, but you will be a hunchback”, “yes, our axes lay for the time being”, “and I would be glad to heaven, but where is the door?

Every now and then riddles are woven into the text, creating picturesque images of either an echo (without a body, but it lives, without a language - it screams), then snow (it lies silent, when it dies, then it roars), then a lock on the door (Does not bark, does not bites, but does not let into the house), then an ax (all your life you bowed, but you have never been affectionate), then a saw (chews, but does not eat).

More N.V. Gogol noted that the Russian people have always expressed their soul in song.

ON THE. Nekrasov constantly refers to this genre. The songs of Matrena Timofeevna tell "about a silk whip, about her husband's relatives." She is picked up by a peasant choir, which testifies to the ubiquity of the suffering of a woman in the family.

Matrena Timofeevna's favorite song, "A Little Light Stands on the Mountain," is heard by her when she decides to seek justice and return her husband from soldiery. This song tells about the choice of a single lover - the owner of a woman's fate. Its location in the poem is determined by the ideological and thematic content of the episode.

Most of the songs introduced by Nekrasov into the epic reflect the horrors of serfdom.

The hero of the song "Corvee" is the unfortunate Kalinushka, whose "skin is all ripped from the bast shoes to the collar, the stomach swells from the chaff." His only joy is a tavern. Even more terrible is the life of Pankratushka, a completely starving plowman who dreams of a big carpet of bread. Because of the eternal hunger, he lost simple human feelings:

Eat all alone

I manage myself

Whether mother or son

Ask - I will not give / "Hungry" /

The poet never forgets about the heavy soldier's share:

German bullets,

Turkish bullets,

French bullets

Russian sticks.

The main idea of the "Soldier's" song is the ingratitude of the state, which left the crippled and sick defenders of the fatherland to the mercy of fate.

Bitter times gave birth to bitter songs. That is why even "Merry" is riddled with irony and talks about the poverty of the peasants "in Holy Rus'."

The song "Salty" tells about the sad side of peasant life - the high cost of salt, which is so necessary for storing agricultural products and in everyday life, but inaccessible to the poor. The poet also uses the second meaning of the word "salty", denoting something heavy, exhausting, difficult.

The fairy-tale angel of mercy acting in the Nekrasov epic, who replaced the demon of rage, sings a song calling honest hearts "to fight, to work."

The songs of Grisha Dobrosklonov, still very bookish, are full of love for the people, faith in their strength, hope to change their fate. The knowledge of folklore is felt in his songs: Grisha often uses its artistic and expressive means (lexicon, constant epithets, general poetic metaphors).

The heroes of “Who Lives Well in Rus'” are characterized by confessionalism, which is so common for works of oral folk art. Pop, then numerous "happy ones", the landowner, Matrena Timofeevna, tell the wanderers about their lives.

And we will see

Church of God

in front of the church

We are baptized for a long time:

"Give her, Lord,

Joy-happiness

Good darling

Alexandrovna".

With the experienced hand of a genius poet, connoisseur and connoisseur of folklore, the poet removes the dialectal phonetic irregularities of genuine lamentations, lamentations, thereby revealing their artistic spirituality:

Drop my tears

Not on land, not on water,

Not to the Lord's temple!

Fall right on your heart

My villain!

He is fluent in N.A. Nekrasov with the genre of the folk ballad and, introducing it into the poem, skillfully imitates both the form (transferring the last line of the verse to the beginning of the next) and vocabulary. He uses folk phraseology, reproduces the folk etymology of book turns, the storytellers' commitment to the geographical and factual accuracy of details:

Ammiral the widower walked the seas,

I walked the seas, I drove ships,

Near Achakov fought with the Turks,

Defeated him.

In the poem, there is a genuine scattering of constant epithets: “gray bunny”, “violent little head”, “black souls”, “fast night”, “white body”, “clear falcon”, “combustible tears”, “reasonable little head”, “red girls ”,“ good fellow ”,“ greyhound horse ”,“ clear eyes ”,“ bright Sunday ”,“ ruddy face ”,“ pea jester ”.

The number seven, traditionally widely used in folklore (seven Fridays a week, slurping jelly for seven miles, seven do not wait for one, measure seven times - cut one, etc.) is also noticeable in the poem, where seven men from seven adjacent villages (Zaplatovo, Dyryavino , Razutovo, Znobishino, Gorelovo, Neelovo, Neurozhayka) set off to wander around the world; seven eagle owls look down on them from seven large trees, and so on. No less often does the poet turn to the number three, also according to the folklore tradition: “three lakes are weeping”, “three lanes of trouble”, “three loops”, “three equity holders”, “three Matryonas” - and so on.

Nekrasov also uses other methods of oral folk art, such as interjections and particles, which give the narrative emotionality: “Oh, swallow! Oh! stupid”, “Chu! the horse is clattering its hooves”, “ah, kosonka! Like gold burns in the sun.

Compound words are common in “To whom it is good to live in Russia”, composed of two synonyms (gad-midge, way-path, melancholy-trouble, mother earth, mother rye, fruit-berries) or single-root words (rad-radekhonek, young -baby) or words reinforced by the repetition of single-root words (tablecloth with a tablecloth, snoring snoring, roaring roars).

Traditional in the poem are folklore diminutive suffixes in words (round, pot-bellied, gray-haired, mustachioed, path), appeals, including to inanimate objects (“oh you, small bird ...”, “Hey, peasant happiness!”, “ Oh, you, dog hunting", "Oh! night, drunken night!"), Negative comparisons

(Not violent winds blow,

Not mother earth sways -

Noise, sing, swear,

Fighting and kissing

At the holiday people).

The events in “To whom it is good to live in Rus'” are set out in chronological order - the traditional composition of folk epic works. Numerous subplots of the poem are predominantly narrative texts. The diverse rhythms of the Nekrasov epic poem are conditioned by the genres of oral folk art: fairy tales, epics, songs, lamentations, lamentations!

The author is a folk storyteller who is fluent in lively folk speech. In the gullible view of peasant readers, it differs little from them, as, for example, wanderers - pilgrims, who captivate their listeners with entertaining stories. In the course of the narration, the narrator discovers the cunning of the mind, beloved by the people, the ability to satisfy their curiosity and fantasy. Christian condemnation is close to his heart

The narrator of the sinfulness of vice and the moral reward of the sufferers and the righteous. And only a sophisticated reader can see behind this role of a folk narrator the face of a great poet, poet-educator, educator and leader.

The poem "To whom it is good to live in Rus'" is written mostly in iambic trimeter with two final unstressed syllables. The poet's poems are not rhymed, they are distinguished by the richness of consonances and rhythms.

Nikolay Alekseevich Nekrasov

Who lives well in Rus'

PART ONE

In what year - count

In what land - guess

On the pillar path

Seven men came together:

Seven temporarily liable,

tightened province,

County Terpigorev,

empty parish,

From adjacent villages:

Zaplatova, Dyryavina,

Razutova, Znobishina,

Gorelova, Neelova -

Crop failure, too,

Agreed - and argued:

Who has fun

Feel free in Rus'?

Roman said: to the landowner,

Demyan said: to the official,

Luke said: ass.

Fat-bellied merchant! -

Gubin brothers said

Ivan and Mitrodor.

Old man Pahom pushed

And he said, looking at the ground:

noble boyar,

Minister of the State.

And Prov said: to the king ...

Man what a bull: vtemyashitsya

In the head what a whim -

Stake her from there

You won’t knock out: they rest,

Everyone is on their own!

Is there such a dispute?

What do passers-by think?

To know that the children found the treasure

And they share...

To each his own

Left the house before noon:

That path led to the forge,

He went to the village of Ivankovo

Call Father Prokofy

Baptize the child.

Pahom honeycombs

Carried to the market in the Great,

And two brothers Gubina

So simple with a halter

Catching a stubborn horse

They went to their own herd.

It's high time for everyone

Return your way -

They are walking side by side!

They walk like they're running

Behind them are gray wolves,

What is further - then sooner.

They go - they perekorya!

They shout - they will not come to their senses!

And time does not wait.

They didn't notice the controversy

As the red sun set

How the evening came.

Probably a whole night

So they went - not knowing where,

When they meet a woman,

Crooked Durandiha,

She did not shout: “Venerable!

Where are you looking at night

Have you thought about going?..”

Asked, laughed

Whipped, witch, gelding

And jumped off...

"Where? .." - exchanged glances

Here are our men

They stand, they are silent, they look down...

The night has long gone

Frequent stars lit up

In high skies

The moon surfaced, the shadows are black

The road was cut

Zealous walkers.

Oh shadows! black shadows!

Who won't you chase?

Who won't you overtake?

Only you, black shadows,

You can not catch - hug!

To the forest, to the path

He looked, was silent Pahom,

I looked - I scattered my mind

And he said at last:

"Well! goblin glorious joke

He played a trick on us!

After all, we are without a little

Thirty miles away!

Home now toss and turn -

We are tired - we will not reach,

Come on, there's nothing to be done.

Let's rest until the sun! .. "

Having dumped the trouble on the devil,

Under the forest along the path

The men sat down.

They lit a fire, formed,

Two ran away for vodka,

And the rest for a while

The glass is made

I pulled the birch bark.

The vodka came soon.

Ripe and snack -

The men are feasting!

Kosushki drank three,

Ate - and argued

Again: who has fun to live,

Feel free in Rus'?

Roman shouts: to the landowner,

Demyan shouts: to the official,

Luke yells: ass;

Fat-bellied merchant, -

The Gubin brothers are screaming,

Ivan and Mitrodor;

Pahom shouts: to the brightest

noble boyar,

Minister of the State,

And Prov shouts: to the king!

Taken more than ever

perky men,

Cursing swearing,

No wonder they get stuck

Into each other's hair...

Look - they've got it!

Roman hits Pakhomushka,

Demyan hits Luka.

And two brothers Gubina

They iron Prov hefty, -

And everyone screams!

A booming echo woke up

Went for a walk, a walk,

It went screaming, shouting,

As if to tease

Stubborn men.

King! - heard to the right

Left responds:

Butt! ass! ass!

The whole forest was in turmoil

With flying birds

By swift-footed beasts

And creeping reptiles, -

And a groan, and a roar, and a rumble!

First of all, a gray bunny

From a neighboring bush

Suddenly jumped out, as if tousled,

And off he went!

Behind him are small jackdaws

At the top of the birches raised

Nasty, sharp squeak.

And here at the foam

With fright, a tiny chick

Fell from the nest;

Chirping, crying chiffchaff,

Where is the chick? - will not find!

Then the old cuckoo

I woke up and thought

Someone to cuckoo;

Taken ten times

Yes, it crashed every time

And started again...

Cuckoo, cuckoo, cuckoo!

Bread will sting

You choke on an ear -

You won't poop!

Seven owls flocked,

Admire the carnage

From seven big trees

Laugh, midnighters!

And their eyes are yellow

They burn like burning wax

Fourteen candles!

And the raven, the smart bird,

Ripe, sitting on a tree

At the very fire.

Sitting and praying to hell

To be slammed to death

Someone!

Cow with a bell

What has strayed since the evening

From the herd, I heard a little

human voices -

Came to the fire, tired

Eyes on men

I listened to crazy speeches

And began, my heart,

Moo, moo, moo!

Silly cow mooing

Small jackdaws squeak.

The boys are screaming,

And the echo echoes everything.

He has one concern -

To tease honest people

Scare guys and women!

Nobody saw him

And everyone has heard

Without a body - but it lives,

Without a tongue - screaming!

Owl - Zamoskvoretskaya

Princess - immediately mooing,

Flying over peasants

Rushing about the ground,

That about the bushes with a wing ...

The fox herself is cunning,

Out of curiosity,

Sneaked up on the men

I listened, I listened

And she walked away, thinking:

"And the devil does not understand them!"

And indeed: the disputants themselves

Hardly knew, remembered -

What are they talking about...

Naming the sides decently

To each other, come to their senses

Finally, the peasants

Drunk from a puddle

Washed, refreshed

Sleep began to roll them ...

In the meantime, a tiny chick,

Little by little, half a sapling,

flying low,

Got to the fire.

Pakhomushka caught him,

He brought it to the fire, looked at it

And he said: "Little bird,

And the nail is up!

I breathe - you roll off the palm of your hand,

Sneeze - roll into the fire,

I click - you will roll dead,

And yet you, little bird,

Stronger than a man!

Wings will get stronger soon

Bye-bye! wherever you want

You will fly there!

Oh you little pichuga!

Give us your wings

We will circle the whole kingdom,

Let's see, let's see

Let's ask and find out:

Who lives happily

Feel free in Rus'?

"You don't even need wings,

If only we had bread

Half a pood a day, -

And so we would Mother Rus'

They measured it with their feet!” -

Said the sullen Prov.

"Yes, a bucket of vodka," -

Added willing

Before vodka, the Gubin brothers,

Ivan and Mitrodor.

“Yes, in the morning there would be cucumbers

Salty ten, "-

The men joked.

“And at noon would be a jug

Cold kvass."

"And in the evening for a teapot

Hot tea…”

While they were talking

Curled, whirled foam

Above them: listened to everything

And sat by the fire.

Chiviknula, jumped up

And in a human voice

Pahomu says:

"Let go of the chick!

For a little chick

I'll give you a big ransom."

– What will you give? -

"Lady's bread

Half a pood a day

I'll give you a bucket of vodka

In the morning I will give cucumbers,

And at noon sour kvass,

And in the evening a seagull!

- And where, little pichuga, -

Gubin brothers asked, -

Find wine and bread

Are you on seven men? -

“Find - you will find yourself.

And I, little pichuga,

I'll tell you how to find it."

- Tell! -

"Go through the woods

Against the thirtieth pillar

A straight verst:

Come to the meadow

Standing in that meadow

Two old pines

Beneath these under the pines

Buried box.

Get her -

That box is magical.

It has a self-assembled tablecloth,

Whenever you wish

Eat, drink!

Quietly just say:

"Hey! self-made tablecloth!

Treat the men!”

At your request

At my command

Everything will appear at once.

Now let the chick go!”

Womb - then ask

And you can ask for vodka

In day exactly on a bucket.

If you ask more

And one and two - it will be fulfilled

At your request,

And in the third, be in trouble!

And the foam flew away

With my darling chick,

And the men in single file

Reached for the road

Look for the thirtieth pillar.

Found! - silently go

Straight, straight

Through the dense forest,

Every step counts.

And how they measured a mile,

We saw a meadow -

Standing in that meadow

Two old pines...

The peasants dug

Got that box

Opened and found

That tablecloth self-assembled!

They found it and shouted at once:

“Hey, self-assembled tablecloth!

Treat the men!”

Look - the tablecloth unfolded,

Where did they come from

Two strong hands

A bucket of wine was placed

Bread was laid on a mountain

And they hid again.

“But why aren’t there cucumbers?”

"What is not a hot tea?"

“What is there no cold kvass?”

Everything suddenly appeared...

The peasants unbelted

They sat down by the tablecloth.

Went here feast mountain!

Kissing for joy

promise to each other

Forward do not fight in vain,

And it's quite controversial

By reason, by God,

On the honor of the story -

Do not toss and turn in the houses,

Don't see your wives

Not with the little guys

Not with old old people,

As long as the matter is controversial

Solutions will not be found

Until they tell

No matter how it is for sure:

Who lives happily

Feel free in Rus'?

Having made such a vow,

In the morning like dead

Men fell asleep...

Illustration by Sergei Gerasimov "Dispute"

One day, seven men converge on the high road - recent serfs, and now temporarily liable "from adjacent villages - Zaplatova, Dyryavin, Razutov, Znobishina, Gorelova, Neyolova, Neurozhayka, too." Instead of going their own way, the peasants start a dispute about who in Rus' lives happily and freely. Each of them judges in his own way who is the main lucky man in Rus': a landowner, an official, a priest, a merchant, a noble boyar, a minister of sovereigns or a tsar.

During the argument, they do not notice that they gave a detour of thirty miles. Seeing that it is too late to return home, the men make a fire and continue to argue over vodka - which, of course, little by little turns into a fight. But even a fight does not help to resolve the issue that worries the men.

The solution is found unexpectedly: one of the peasants, Pahom, catches a warbler chick, and in order to free the chick, the warbler tells the peasants where they can find a self-assembled tablecloth. Now the peasants are provided with bread, vodka, cucumbers, kvass, tea - in a word, everything they need for a long journey. And besides, the self-assembled tablecloth will repair and wash their clothes! Having received all these benefits, the peasants give a vow to find out "who lives happily, freely in Rus'."

The first possible "lucky man" they met along the way is a priest. (It was not for the oncoming soldiers and beggars to ask about happiness!) But the priest's answer to the question of whether his life is sweet disappoints the peasants. They agree with the priest that happiness lies in peace, wealth and honor. But the pop does not possess any of these benefits. In haymaking, in stubble, in a dead autumn night, in severe frost, he must go where there are sick, dying and being born. And every time his soul hurts at the sight of grave sobs and orphan sorrow - so that his hand does not rise to take copper nickels - a miserable reward for the demand. The landlords, who formerly lived in family estates and got married here, baptized children, buried the dead, are now scattered not only in Rus', but also in distant foreign land; there is no hope for their reward. Well, the peasants themselves know what honor the priest is: they feel embarrassed when the priest blames obscene songs and insults against priests.

Realizing that the Russian pop is not among the lucky ones, the peasants go to the festive fair in the trading village of Kuzminskoye to ask the people about happiness there. In a rich and dirty village there are two churches, a tightly boarded-up house with the inscription "school", a paramedic's hut, a dirty hotel. But most of all in the village of drinking establishments, in each of which they barely manage to cope with the thirsty. Old man Vavila cannot buy his granddaughter goat's shoes, because he drank himself to a penny. It’s good that Pavlusha Veretennikov, a lover of Russian songs, whom everyone calls “master” for some reason, buys a treasured gift for him.

Wandering peasants watch the farcical Petrushka, watch how the women are picking up book goods - but by no means Belinsky and Gogol, but portraits of fat generals unknown to anyone and works about "my lord stupid." They also see how a busy trading day ends: rampant drunkenness, fights on the way home. However, the peasants are indignant at Pavlusha Veretennikov's attempt to measure the peasant by the master's measure. In their opinion, it is impossible for a sober person to live in Rus': he will not endure either overwork or peasant misfortune; without drinking, bloody rain would have poured out of the angry peasant soul. These words are confirmed by Yakim Nagoi from the village of Bosovo - one of those who "work to death, drink half to death." Yakim believes that only pigs walk the earth and do not see the sky for a century. During a fire, he himself did not save money accumulated over a lifetime, but useless and beloved pictures that hung in the hut; he is sure that with the cessation of drunkenness, great sadness will come to Rus'.

Wandering men do not lose hope of finding people who live well in Rus'. But even for the promise to give water to the lucky ones for free, they fail to find those. For the sake of gratuitous booze, both an overworked worker, and a paralyzed former courtyard, who for forty years licked the master's plates with the best French truffle, and even ragged beggars are ready to declare themselves lucky.

Finally, someone tells them the story of Ermil Girin, a steward in the estate of Prince Yurlov, who has earned universal respect for his justice and honesty. When Girin needed money to buy the mill, the peasants lent it to him without even asking for a receipt. But Yermil is now unhappy: after the peasant revolt, he is in jail.

About the misfortune that befell the nobles after the peasant reform, the ruddy sixty-year-old landowner Gavrila Obolt-Obolduev tells the peasant wanderers. He recalls how in the old days everything amused the master: villages, forests, fields, serf actors, musicians, hunters, who belonged undividedly to him. Obolt-Obolduev tells with emotion how on the twelfth holidays he invited his serfs to pray in the manor's house - despite the fact that after that they had to drive women from all over the estate to wash the floors.

And although the peasants themselves know that life in serf times was far from the idyll drawn by Obolduev, they nevertheless understand: the great chain of serfdom, having broken, hit both the master, who at once lost his usual way of life, and the peasant.

Desperate to find a happy man among the men, the wanderers decide to ask the women. The surrounding peasants remember that Matrena Timofeevna Korchagina lives in the village of Klin, whom everyone considers lucky. But Matrona herself thinks differently. In confirmation, she tells the wanderers the story of her life.

Before her marriage, Matryona lived in a non-drinking and prosperous peasant family. She married Philip Korchagin, a stove-maker from a foreign village. But the only happy night for her was that night when the groom persuaded Matryona to marry him; then the usual hopeless life of a village woman began. True, her husband loved her and beat her only once, but soon he went to work in St. Petersburg, and Matryona was forced to endure insults in her father-in-law's family. The only one who felt sorry for Matryona was grandfather Saveliy, who lived out his life in the family after hard labor, where he ended up for the murder of the hated German manager. Savely told Matryona what Russian heroism is: a peasant cannot be defeated, because he "bends, but does not break."

The birth of the first-born Demushka brightened up the life of Matryona. But soon her mother-in-law forbade her to take the child into the field, and old grandfather Savely did not follow the baby and fed him to the pigs. In front of Matryona, the judges who arrived from the city performed an autopsy on her child. Matryona could not forget her first child, although after she had five sons. One of them, the shepherd Fedot, once allowed a she-wolf to carry away a sheep. Matrena took upon herself the punishment assigned to her son. Then, being pregnant with her son Liodor, she was forced to go to the city to seek justice: her husband, bypassing the laws, was taken to the soldiers. Matryona was then helped by the governor Elena Alexandrovna, for whom the whole family is now praying.

By all peasant standards, the life of Matryona Korchagina can be considered happy. But it is impossible to tell about the invisible spiritual storm that passed through this woman - just like about unrequited mortal insults, and about the blood of the firstborn. Matrena Timofeevna is convinced that a Russian peasant woman cannot be happy at all, because the keys to her happiness and free will are lost from God himself.

In the midst of haymaking, wanderers come to the Volga. Here they witness a strange scene. A noble family swims up to the shore in three boats. The mowers, who have just sat down to rest, immediately jump up to show the old master their zeal. It turns out that the peasants of the village of Vakhlachina help their heirs to hide the abolition of serfdom from the landowner Utyatin, who has lost his mind. For this, the relatives of the Last Duck-Duck promise the peasants floodplain meadows. But after the long-awaited death of the Afterlife, the heirs forget their promises, and the whole peasant performance turns out to be in vain.

Here, near the village of Vakhlachin, wanderers listen to peasant songs - corvée, hungry, soldier's, salty - and stories about serf times. One of these stories is about the serf of the exemplary Jacob the faithful. Yakov's only joy was to please his master, the petty landowner Polivanov. Samodur Polivanov, in gratitude, beat Yakov in the teeth with his heel, which aroused even greater love in the lackey's soul. By old age, Polivanov lost his legs, and Yakov began to follow him as if he were a child. But when Yakov's nephew, Grisha, decided to marry the serf beauty Arisha, out of jealousy, Polivanov sent the guy to the recruits. Yakov began to drink, but soon returned to the master. And yet he managed to take revenge on Polivanov - the only way available to him, in a lackey way. Having brought the master into the forest, Yakov hanged himself right above him on a pine tree. Polivanov spent the night under the corpse of his faithful serf, driving away birds and wolves with groans of horror.

Another story - about two great sinners - is told to the peasants by God's wanderer Iona Lyapushkin. The Lord awakened the conscience of the ataman of the robbers Kudeyar. The robber prayed for sins for a long time, but all of them were released to him only after he killed the cruel Pan Glukhovsky in a surge of anger.

Wandering men also listen to the story of another sinner - Gleb the elder, who hid the last will of the late widower admiral for money, who decided to free his peasants.

But not only wandering peasants think about the happiness of the people. The son of a sacristan, seminarian Grisha Dobrosklonov, lives in Vakhlachin. In his heart, love for the deceased mother merged with love for the whole of Vahlachina. For fifteen years, Grisha knew for sure whom he was ready to give his life, for whom he was ready to die. He thinks of all mysterious Rus' as a miserable, abundant, powerful and powerless mother, and expects that the indestructible strength that he feels in his own soul will still be reflected in her. Such strong souls, like those of Grisha Dobrosklonov, the angel of mercy himself calls for an honest path. Fate prepares Grisha "a glorious path, a loud name of the people's intercessor, consumption and Siberia."

If the wanderer men knew what was happening in the soul of Grisha Dobrosklonov, they would surely understand that they could already return to their native roof, because the goal of their journey had been achieved.

retold

ON THE. Nekrasov was always not just a poet - he was a citizen who was deeply concerned about social injustice, and especially about the problems of the Russian peasantry. The cruel treatment of the landowners, the exploitation of women's and children's labor, a bleak life - all this was reflected in his work. And in 18621, the seemingly long-awaited liberation comes - the abolition of serfdom. But was it actually liberation? It is to this topic that Nekrasov devotes “To whom it is good to live in Rus'” - the sharpest, most famous - and his last work. The poet wrote it from 1863 until his death, but the poem still came out unfinished, so it was prepared for printing based on fragments of the poet's manuscripts. However, this incompleteness turned out to be significant in its own way - after all, for the Russian peasantry, the abolition of serfdom did not become the end of the old and the beginning of a new life.

“Who should live well in Rus'” is worth reading in full, because at first glance it may seem that the plot is too simple for such a complex topic. The dispute of seven peasants about who is happy to live in Rus' cannot be the basis for revealing the depth and complexity of the social conflict. But thanks to Nekrasov's talent in revealing characters, the work is gradually revealed. The poem is quite difficult to understand, so it is best to download its full text and read it several times. It is important to pay attention to how different the understanding of happiness is shown by a peasant and a gentleman: the first believes that this is his material well-being, and the second - that this is the least possible number of troubles in his life. At the same time, in order to emphasize the idea of \u200b\u200bthe spirituality of the people, Nekrasov introduces two more characters who come from his environment - these are Yermil Girin and Grisha Dobrosklonov, who sincerely want happiness for the entire peasant class, and so that no one is offended.

The poem “To whom it is good to live in Rus'” is not idealistic, because the poet sees problems not only in the nobility, which is mired in greed, arrogance and cruelty, but also among the peasants. This is primarily drunkenness and obscurantism, as well as degradation, illiteracy and poverty. The problem of finding happiness personally for oneself and for the whole people as a whole, the struggle against vices and the desire to make the world a better place are relevant today. So even in its unfinished form, Nekrasov's poem is not only a literary, but also a moral and ethical model.

N. A. Nekrasov worked on his poem for a long time - from the 1860s until the end of his life. During his lifetime, individual chapters of the work were published, but it was fully published only in 1920, when K. I. Chukovsky decided to release the complete works of the poet. In many ways, the work “To whom it is good to live in Rus'” is built on the elements of Russian folk art, the language of the poem is close to that which was understandable to the peasants of that time.

Main characters

Despite the fact that Nekrasov planned to cover the life of all classes in his poem, the main characters of “Who Lives Well in Rus'” are still peasants. The poet paints their life in gloomy colors, especially sympathizing with women. The most striking images of the work are Ermila Girin, Yakim Nagoi, Savely, Matrena Timofeevna, Klim Lavin. At the same time, not only the world of the peasantry appears before the eyes of the reader, although the main emphasis is placed on it.

Often, schoolchildren receive as homework a brief description of the heroes of “Who Lives Well in Rus'” and their characteristics. To get a good assessment, it is necessary to mention not only the peasants, but also the landowners. This is Prince Utyatin with his family, Obolt-Obolduev, a generous governor, a German manager. The work as a whole is characterized by the epic unity of all acting heroes. However, along with this, the poet also presented many personalities, individualized images.

Ermila Girin

This hero "To whom it is good to live in Rus'", according to those who know him, is a happy person. The people around him appreciate him, and the landowner shows respect. Ermila is engaged in socially useful work - she runs a mill. He works on it without deceiving ordinary peasants. Kirin is trusted by everyone. This is manifested, for example, in the situation of collecting money for an orphan's mill. Ermila finds herself in the city without money, and the mill is put up for sale. If he does not have time to return for the money, then Altynnikov will get it - this will not be good for anyone. Then Jirin decides to appeal to the people. And people unite in order to do a good deed. They believe that their money will go to good causes.

This hero of “Who should live well in Rus'” was a clerk and helped those who do not know it to learn to read and write. However, the wanderers did not consider Yermila happy, because he could not stand the most difficult test - power. Instead of his own brother, Jirin gets into the soldiers. Ermila repents of her deed. He can no longer be considered happy.

Yakim Nagoi

One of the main characters of "Who Lives Well in Rus'" is Yakim Nagoi. He defines himself as follows - "works to death, drinks half to death." Nagogo's story is simple and at the same time very tragic. Once he lived in St. Petersburg, but ended up in prison, lost his estate. After that, he had to settle in the countryside and take on exhausting work. In the work, he is entrusted with protecting the people themselves.

The spiritual needs of man are indestructible

During the fire, Yakim loses most of what he has acquired, as he begins to save the pictures that he has acquired for his son. However, even in his new dwelling, Nagoi takes over the old one, buys other pictures. Why does he decide to save these things, at first glance, which are simple knick-knacks? A person tries to preserve what is dearest to him. And these pictures turn out to be more expensive for Yakim than money earned by hellish labor.

The life of the heroes of “Who Lives Well in Rus'” is an ongoing work, the results of which fall into the wrong hands. But the human soul cannot be content with an existence in which there is only room for endless hard labor. The Spirit of the Naked requires something high, and these pictures, oddly enough, are a symbol of spirituality.

Endless adversity only strengthens his position in life. In Chapter III, he delivers a monologue in which he describes in detail his life - this is hard labor, the results of which are in the hands of three equity holders, disasters and hopeless poverty. And by these disasters he justifies his drunkenness. It was the only joy for the peasants, whose only occupation was hard work.

The place of a woman in the poet's work

Women also occupy a significant place in Nekrasov's work. The poet considered their share the most difficult - after all, it was on the shoulders of Russian peasant women that the duty of raising children, preserving the hearth and love in harsh Russian conditions fell. In the work “To whom it is good to live in Rus'”, the heroes (more precisely, the heroines) bear the heaviest cross. Their images are described in most detail in the chapter entitled "Drunken Night". Here you can face the difficult fate of women working as servants in cities. The reader meets Daryushka, who has grown thin from overwork, women whose situation in the house is worse than in hell - where the son-in-law constantly takes up the knife, "look, he will kill him."

Matryona Korchagin

The culmination of the female theme in the poem is the part called "Peasant Woman". Her main character is Matryona Timofeevna by the name of Korchagina, whose life is a generalization of the life of a Russian peasant woman. On the one hand, the poet demonstrates the gravity of her fate, but on the other, the unbending will of Matryona Korchagina. The people consider her "happy", and wanderers set off on a journey to see this "miracle" with their own eyes.

Matryona succumbs to their persuasion and talks about her life. She considers her childhood the happiest time. After all, her family was caring, no one drank. But soon the moment came when it was necessary to get married. Here she seemed to be lucky - her husband loved Matryona. However, she becomes the younger daughter-in-law, and she has to please everyone and everyone. She could not even count on a kind word.

Only with grandfather Savely Matryona could open her soul, cry. But even the grandfather, although not of his own free will, caused her terrible pain - he did not see after the child. After that, the judges accused Matryona herself of killing the baby.

Is the heroine happy?

The poet emphasizes the helplessness of the heroine and, with the words of Savely, tells her to endure, because "we cannot find the truth." And these words become a description of the whole life of Matryona, who had to endure losses, grief, and resentment from the landowners. Only once does she manage to “find the truth” - to “beg” her husband from the unfair soldiery from the landowner Elena Alexandrovna. Perhaps that is why Matryona began to be called "happy." And perhaps because, unlike some other heroes of “Who Lives Well in Rus'”, she did not break down, despite all the hardships. According to the poet, the fate of a woman is the most difficult. After all, she has to suffer from lawlessness in the family, and worry about the lives of loved ones, and perform back-breaking work.

Grisha Dobrosklonov

This is one of the main characters of "Who lives well in Rus'." He was born in the family of a poor clerk, who was also lazy. His mother was the image of a woman, which was described in detail in the chapter entitled "Peasant Woman". Grisha managed to understand his place in life already at a young age. This was facilitated by labor hardening, a hungry childhood, a generous character, vitality and perseverance. Grisha became a fighter for the rights of all the downtrodden, he stood for the interests of the peasants. In the first place he had not personal needs, but social values. The main features of the hero are unpretentiousness, high efficiency, the ability to sympathize, education and a sharp mind.

Who can find happiness in Rus'

Throughout the work, the poet tries to answer the question about the happiness of the heroes "Who in Rus' should live well." Perhaps it is Grisha Dobrosklonov who is the happiest character. After all, when a person does a good deed, he gets a pleasant feeling of his own worth. Here the hero saves the whole people. From childhood, Grisha sees unfortunate and oppressed people. Nekrasov considered the ability to compassion a source of patriotism. The poet has a person who sympathizes with the people, raises a revolution - this is Grisha Dobrosklonov. His words reflect the hope that Rus' will not perish.

landowners

Among the heroes of the poem "To whom it is good to live in Rus'", as it was indicated, there are also quite a few landowners. One of them is Obolt-Obolduev. When the peasants ask him if he is happy, he only laughs in response. Then, with some regret, he recalls the past years, which were full of prosperity. However, the reform of 1861 abolished serfdom, although it was not carried through to the end. But even the changes that have taken place in public life cannot force the landowner to work and honor the results of the work of other people.

To match him, another hero of Nekrasov’s “Who Lives Well in Rus'” is Utyatin. All his life he was "freaking and fooling", and when the social reform came, he had a stroke. His children, in order to receive an inheritance, together with the peasants, play a real performance. They inspire him that he will not be left with anything, and serfdom still dominates in Rus'.

Grandfather Savely

The characterization of the heroes of "Who Lives Well in Rus'" would be incomplete without a description of the image of grandfather Savely. The reader gets to know him already when he lived a long and hard life. In his old age, Savely lives with his son's family, he is Matryona's father-in-law. It is worth noting that the old man does not like his family. After all, households do not have the best characteristics.

Even in his native circle, Savely is called "branded, convict." But he is not offended by this and gives a worthy answer: "Branded, but not a slave." Such is the nature of this hero "Who in Rus' live well." A brief description of the character of Savely can be supplemented by the fact that he is not averse to sometimes playing a trick on members of his family. The main thing that is noted when meeting this character is his difference from the rest, both from his son and from other inhabitants of the house.