Hello student. Hello student The mysterious Renaissance as a consequence of chronological errors

The reliability of the opinion of the prophet and the historian is comparable. Today it is quite clearly visible that chronology - contrary to the traditional idea of history - is basically an exact science, and only as such is it capable of resolving its contradictions. The study of the movement of the Moon became the impetus for the creation of a real chronology. The version of ancient chronology accepted today is not the only one. The complexity of natural scientific methods for researching chronology makes it difficult for historians to use them.

Chronology plays an important role in history and source studies. It allows you to determine the time interval between events of the past and present, if you can convert the chronological data of the document into chronological units, for example, into Julian dates BC. e. or n. e. Many historical conclusions and concepts depend on the exact date of the events described in the source.

One of the classics called the historian a prophet looking back. This statement is not only figurative, but also accurate. For natural reasons, the reliability of the opinion of the prophet looking forward and the historian looking back turns out to be comparable and not too high. The prophet even finds himself in a privileged position, since his opinion is easier to check, you just need to be patient. In addition, an influential prophet can simply influence the future (as one science fiction writer said, not to predict the future, but to prevent it). The historian does not have the opportunity to influence the past, and all attempts to do this are incorrect.

Why did the question of ancient chronology arise today in a book primarily devoted to the description of statistical methods for analyzing texts? In the 15th–16th centuries, chronology was considered a branch of mathematics. Then it gradually turned into a section of historical science and is considered as an area of knowledge that has been largely researched and needs only individual clarifications that do not affect the entire edifice of chronology as a whole. However, it turns out that the chronology of antiquity accepted today carries deep contradictions. And it was quite natural to try to eliminate at least some of these difficulties with the help of modern mathematical and physical methods. Today it is quite clearly visible that chronology - contrary to the traditional idea of history - is basically an exact science, and only as such is it capable of resolving its contradictions.

The impetus for this work was the study of an important issue in celestial mechanics related to the analysis of the dates of ancient eclipses. It was about calculating the so-called parameter D" in the theory of the motion of the Moon. The parameter characterizes acceleration and is a function of time over a large interval of historical time. The calculations were performed by the famous modern astronomer Robert Newton. He discovered that the parameter D" strangely depends on time, making an unexpected leap in the interval of the 8th–10th centuries AD. e. The jump contradicts the gravitational theory and is so incredible that Robert Newton had to introduce “non-gravitational forces” specifically for the Earth-Moon system, which in no way manifest themselves in other situations.

A.T. Fomenko became interested in this incomprehensible effect and checked the work of R. Newton. The inspection confirmed that the work was carried out at the highest scientific level. Robert Newton, being a specialist in celestial navigation and the theory of calculating the trajectories of celestial bodies and vehicles, trusted ancient dates and tried to explain the effect he discovered without raising the question of the reliability of ancient chronology. However, the idea of checking the accuracy of the dates of those ancient (including ancient) eclipses on which the work of R. Newton was based turned out to be more natural.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the famous Russian encyclopedist N.A. Morozov analyzed the dating of ancient eclipses and stated that almost all of them need revision. For many eclipses, he proposed new dates closer to our time. A.T. Fomenko used his tables to replace the traditional dates of eclipses, repeated R. Newton’s calculations and obtained a very impressive result. Graph D" radically straightened and turned into an almost horizontal line predicted by the standard gravitational curve. The mysterious jump disappeared, and with it the need to invent some kind of fantastic “non-gravitational interactions” disappeared.

Analysis of a large amount of historical information has shown that the version of ancient chronology accepted today is not the only one. Thus, the three ancient eclipses described by the famous historian Thucydides could not have occurred in the 5th century BC. e., and in the 11th or even 12th century AD. e., - there are only two astronomically accurate solutions. There is a conflict between astronomy and traditional chronology.

It turned out that for a long time, various scientists in various countries insisted on the need for a major revision of the system of ancient dates. The scope of this revision requires time and effort. Today, scientific analysis of chronology is carried out mainly by mathematicians and physicists, which is largely due to the complexity of natural scientific research methods. Unfortunately, the bulk of historians have so far turned out to be aloof from this activity, concentrating their efforts on trying to slow it down. Among the reasons for this - in addition to the lack of knowledge in the field of modern methods for processing chronological information - is subjectivity, which has already manifested itself more than once in the social sciences.

Here we can recall Lev Landau’s joke that sciences are natural, unnatural and unnatural. However, you should not worry too much about the fact that some sciences are more subjective and emotional, while others are more objective and dry. Each technique has its own charm, it is important to learn how to apply it to the place.

1.2. WHO CREATED THE CHRONOLOGY AND WHEN

The traditional chronology developed in the 16th–19th centuries. Dating of a document is usually done by comparison with data whose dating is considered already known. Christian historians have placed secular chronography in the service of sacred history. Due to the ambiguity of Kabbalistic calculations, the date of creation of the world varies from 5969 BC. e. before 3761 BC e. Two hundred versions of the date of creation of the world can be associated with a comparable number of versions of chronology. The founder of traditional chronology, I. Scaliger, was able to “solve” the insoluble problem of squaring the circle.

The traditional global chronology, which assigns dates in the Julian calendar to all the main events of ancient history, was formed as a result of the long work of several generations of chronologists of the 16th–19th centuries. Among its creators were, in particular, mathematicians and astronomers. Subsequent dating of the facts contained in any document that first came into the hands of historians is usually carried out approximately according to the following scheme.

Let the Roman consul be mentioned in a historical text describing certain events. By now, the compilation of a sequential list of consuls for a period of 1050 years - from Junius, son of Marcus Brutus, and Tarquinius Collatinus (509 BC) to Basil (541 AD) - has been completed in basic terms. By finding in this list the name of the consul mentioned in the text under study and referring to the years of his reign in accordance with the dating of the entire list, historians tie the events described in the document to a timeline.

Thus, most modern dating methods are based on the principles of comparing the data of the document under study with data whose dating is considered already known. It is no coincidence that an example is taken from Roman chronology. As the famous modern American chronologist E. Bickerman writes, “all other datings of ancient chronology can be linked with our chronology using direct or indirect synchronisms with Roman dates.” In other words, Roman chronology is the "vertebral column" of the entire global chronology of Europe, as well as the Mediterranean, Middle East, Egypt and other regions.

The founders of traditional chronology as a science are considered to be I. Scaliger (1540–1609) and D. Petavius (Petavius) (1583–1652). However, a series of their works ( Scaliger I. Opus novum de emendatione temporum. Lutetiac. Paris, 1583. Thesaurum temporum. 1606; Petavius D. De Doctrina temporum. Paris, 1627) not completed. As E. Bickerman notes, “there is no sufficiently complete study of ancient chronology that meets modern requirements.” Therefore, it would be more correct to call the traditional chronology the Scaliger-Petavius version. This version was not the only one. E. Bickerman generally speaks with regret about the “chaos of medieval dating.”

The shortcomings of scientific substantiations of traditional chronology are explained not only by the huge volume of processed material, but also by objective difficulties. The first difficulty should be noted that, as A.Ya. points out. Gurevich, “for centuries, history remained predominantly church history, and it was written, as a rule, by clergy.”

It is believed that the early foundations of chronology were laid by Eusebius Pamphilus (IV century AD). and Blessed Jerome. The work of Eusebius “History of Times from the Beginning of the World to the Council of Nicaea” (the so-called “Chronicle”) and the work of Jerome were discovered only in the late Middle Ages. Moreover, it turns out that “the original (Eusebius) now exists only in fragments and is supplemented by a free Latin translation of Bl. Jerome." It is curious that Nikephoros Callistus in the 14th century attempted to write a new version of the history of the first three centuries, “but he could do nothing more than repeat what Eusebius had said.” Since the work of Eusebius was published later than the work of Nikephoros - only in 1544 - a pertinent question is: is Eusebius's book based on the work of Nikephoros? Writers today regularly face authorship problems of this kind, and there is no reason to believe that things were different in the past.

Global chronologies were very often based on a mechanical interpretation of numbers collected in religious sources, which were infallible and, in the opinion of the interpreter, had a deep meaning. For example, as a result of such Kabbalistic exercises, J. Usher (Usserius, Usher) suggested that the world was created on the morning of Sunday, October 23, 4004 BC. e. Treatises on the analysis of ancient chronology were written by religious scholastics in parallel with the writing of dissertations in which they calculated how many devils could fit on the tip of a needle. However, ironically, chronological treatises have received greater historical resonance. The secular chronology that emerged later is entirely based on church chronology. Thus, E. Bickerman notes: “Christian historians put secular chronography in the service of sacred history... Jerome’s compilation was the basis of chronological knowledge in the West.”

Due to the significant ambiguity and doubtfulness of Kabbalistic calculations, for example, the date of the creation of the world varies in different documents within significant limits and differs by 2100 years. There are about 200 (!) versions of this date, which can be matched with a comparable number of chronology versions. Let us give only basic examples of the date of creation of the world:

5969 BC e. - Antiochian, Theophilus;

5872 BC e. - the so-called dating of 70 interpreters;

5551 BC e. - Augustine;

5515 BC e., as well as 5507 - Theophilus;

5508 BC e. - Byzantine, so-called Constantinople;

5500 BC e. - Hippolytus and Sextus Julius Africanus;

5493 BC e., as well as 5472 or 5624 - Alexandrian, era of Annian;

5199 BC e. - Eusebius of Caesarea;

4700 BC e. - Samaritan;

4004 BC e. - Jewish, Asher;

3941 BC e. - Jerome;

3761 BC e. - Jewish.

The question of the “correct date of creation of the world” is very important. A huge number of documents date the events described in years “from the creation of the world,” and therefore thousand-year discrepancies in the choice of the date of creation greatly affect the dating of all documents of this type.

The sanctification of chronological dates by church authority until the 18th century prevented their critical analysis and revision. For example, Scaliger called the works of his predecessor Eusebius “divine.” Being brought up on unconditional worship of the authority of their predecessors, chronologists of the 16th–17th centuries were not always in harmony with common sense, mathematics and logic and reacted sharply to criticism from outside.

The same Scaliger clearly demonstrates his attitude towards scientific criticism in the next episode. The author of a chronology highly regarded in the scientific world became a passionate quadraturist. Let us recall that this was the name given to people who tried, using a compass and a ruler, to construct a square equal in area to the given circle. It has been irrefutably proven that this problem is mathematically insoluble. Scaliger published a book in which he claimed that he had established the “true quadrature”. No matter how the best mathematicians of the era - Viet, Clavius - tried to prove to him that the reasoning was incorrect, everything was useless. Scaliger and his supporters, furiously defending their opinions, did not admit anything, responded with abuse and contemptuous epithets, ultimately declaring all geometers complete ignoramuses in the field of geometry.

Scaliger was the first (together with Petavius) to use the astronomical method to confirm (but by no means critically verify) chronology. As is believed today, he thereby turned his version into a “scientific” one. This touch of “scientificness,” combined with church authority, turned out to be sufficient for chronologists of the 17th–18th centuries to completely trust the version of Scaliger that reached them (and was already largely ossified). By the 19th century, the total volume of chronological material had increased so much that it aroused involuntary respect by its very existence. As a result, chronologists of the 19th century saw their task only in minor clarifications of dates. In the 20th century, the problem of dating was considered basically already solved, and chronology finally froze in the form in which it emerged from the writings of Eusebius, Jerome, Theophilus, Augustine, Hippolytus, Clement of Alexandria, Usher, Scaliger, Petavius.

Nevertheless, as chronology develops and it frees itself from the pressure of authorities, new generations of scientists discover serious difficulties in reconciling many of these sources with Scaliger’s version. For example, it was discovered that Jerome made an error of a hundred (!) years in his description of the events of his time. The Sassanian tradition separated Alexander the Great from the Sassanids by 226 years, and modern chronologists have increased this interval to 557 years (a gap of more than three hundred years!). The basics of Egyptian chronology also came to us through the filter of Christian chronologists: the list of kings compiled by Manetho was preserved only in excerpts from Christian authors.

1.3. ISAAC NEWTON AS A CRITIC OF TRADITIONAL CHRONOLOGY

Isaac Newton is the greatest scientist in the history of mankind, whose works in physics and mathematics still form the basis of everyday and scientific perception of the world around us. It would be natural if a modern person, who sees the world through the eyes of I. Newton, at least partially accepted his view of history. I. Newton's chronology is significantly shorter than the traditional one. He revised historical data up to 200 BC. e., rejuvenating the main part of the events, and making some events more ancient. Part of the history of Ancient Greece has been “lifted up” 300 years closer to us. The history of Ancient Egypt, instead of several thousand years, is compressed into 330 years, with some fundamental dates “raised” by 1800 years. As before, as now, authors are afraid of suffering for publishing according to a statistically reliable chronology.

Isaac Newton (1642–1727) is the greatest scientist in the history of mankind, whose works in physics and mathematics still form the basis of the everyday and scientific perception of the world around the vast majority of people. This English mathematician, mechanic, astronomer and physicist, president of the Royal Society of London, created classical mechanics and developed (independently from G. Leibniz) differential and integral calculus. He discovered the dispersion of light, chromatic aberration, studied interference and diffraction, developed the corpuscular theory of light, and put forward a hypothesis that combined corpuscular and wave concepts. Built a reflecting telescope. He discovered the law of universal gravitation, created the theory of the movement of celestial bodies and the foundations of celestial mechanics. This list of Newton's scientific achievements is far from complete.

Such a person rightfully occupies a special place among critics of the Scaliger-Petavius version. Isaac Newton is the author of several profound works on chronology, in which he came to the conclusion that the Scaligerian version was erroneous in some of its important sections. These studies of his are little known to the modern reader, although previously there were heated debates around them. Nevertheless, it would be natural if modern man, who, as noted above, sees the world mainly through the eyes of I. Newton, at least partially accepted his view of history. Newton's major chronological works are A Brief Chronicle of Historical Events, from the First in Europe to the Conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great and A Correct Chronology of the Ancient Kingdoms (Fig. 1-1).

Rice. 1–1. Title page of Isaac Newton's book. Newton Isaac. The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms amended. To which is Prefix"d, A Short Chronicle from the First Memory of Things in Europe, to the Conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great. - London, J. Tonson, 1728.

Based on the logical analysis of the natural scientific approach, I. Newton subjected the chronology of antiquity to a strong transformation. He reviewed all the main literature on ancient history and all the main sources, starting with ancient and eastern mythology. The work lasted 40 years, requiring intense research and enormous erudition. Some, but very few, events he even made more ancient. This applies, for example, to the legendary campaign of the Argonauts. According to I. Newton, this campaign did not take place in the 10th century BC. e., as was then believed, and in the 14th century BC. e. But in general, I. Newton’s chronology is significantly shorter than Scaliger’s, that is, accepted today. He moved most of the events dating earlier than the era of Alexander the Great “upward”, towards rejuvenation, that is, closer to us. This revision is not as radical as in the works of N.A. Morozov, who believed that the Scaligerian version of the chronology of antiquity is reliable only starting from the 4th century AD. e.

It should be noted that in his chronological studies I. Newton revised only dates approximately earlier than 200 BC. e. His observations were scattered, and he was unable to detect any system in these, at first glance, chaotic re-datings. He focused mainly on the chronology of Ancient Egypt and Ancient Greece.

For example, the traditional version of chronology places the beginning of the reign of the first Egyptian pharaoh Menes (Mena) around 3000 BC. e. And according to I. Newton, this event dates back to only 946 BC. e. So the shift “up” is approximately 2000 years. Another example is the myth of Theseus, which today dates from the 15th century BC. e. I. Newton claims that these events took place around 936 BC. e. Therefore, the proposed "upward" date shift is approximately 700 years. If today the famous Trojan War dates back to approximately 1225 BC. e., then I. Newton claims that this event occurred in 904 BC. e. Therefore, the upward shift in dates is approximately 330 years.

The main conclusions of I. Newton can be formulated as follows. Part of the history of Ancient Greece was “raised” by him “up” in time, on average 300 years closer to us. The history of Ancient Egypt, which covers, according to the Scaligerian version, several thousand years, from approximately 3000 BC. e. and higher - “raised up” and compressed into a period of time only 330 years long (from 946 BC to 617 BC). At the same time, some fundamental dates of ancient Egyptian history were “raised” by I. Newton “up” by approximately 1800 years.

It is significant that I. Newton apparently feared that the publication of a book on chronology would create many problems for him. It is worth noting that the situation has changed little today and authors continue to suffer for publishing according to a statistically reliable chronology. The “Brief Chronicle” was rewritten several times by I. Newton until his death in 1727.

It is curious that the book was not prepared by I. Newton for publication. However, rumors about I. Newton's chronological research spread, and the Princess of Wales expressed a desire to get acquainted with them. I. Newton gave her the manuscript on the condition that this text would not fall into the hands of unauthorized persons. The same thing happened with Abbe Conti. However, having returned to Paris, Abbe Conti began to give the manuscript to interested scientists. As a result, M. Freret translated the manuscript into French, adding his own historical review to it.

This translation soon reached the Parisian bookseller G. Gavelier, who, dreaming of publishing I. Newton’s work, wrote him a letter in May 1724. Having received no response from I. Newton, he wrote him a new letter in March 1725, informing him that he considered his silence as consent to publication along with Frere's remarks. Again there was no answer. Then Gavelier asked his London friend to get an answer personally from I. Newton.

The meeting took place on May 27, 1725, and I. Newton gave a negative answer. However, it was too late. The book has already been published (Abrege de Chronologie de M. Le Chevalier Newton, fait par lui-meme, et traduit sur le manuscript Angelois. With observation by M. Freret. Edited by the Abbe Conti, 1725). I. Newton received a copy of the book on November 11, 1725. After this, he published a letter in the “Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society” (“Transactions of the Royal Society”, v.33, 1725, p.315), where he accused Abbot Conti of breaking his promise and publishing the work against the will of the author. With the advent of attacks from Father Souciet in 1726, I. Newton announced that he was preparing for publication a new, more extensive and detailed book on ancient chronology. However, all these events took place shortly before the death of I. Newton in 1727. He did not manage to publish a more detailed book, and traces of it were lost.

Most likely, the complex history of the publication of the “Brief Chronicle” is explained by the fact that the wise I. Newton was seriously afraid of the consequences of the appearance of this book. Such fears of the creators of the new chronology at all times had good grounds.

On this occasion, I remember one of the ideologists of this science, professor, doctor of physical and mathematical sciences Mikhail Mikhailovich Postnikov, who in 1984 told me approximately the following. The Central Committee of the CPSU warned him against research on statistically reliable chronology with the following argument. The dissertation of one of the founders of Marxism is dedicated to the historian Tacitus, whom Postnikov, not without reason, called a false figure. Such a fact, according to the ideologists of communism, could cast a shadow on the scientific foundations of Marxism and was therefore unacceptable...

Quite a lot of responses appeared to the work of I. Newton in the press of the mid-18th century. They belonged mainly to historians and philologists, were of a negative nature and characterized this work as “the delusions of an honorable amateur.” There were, however, responses in support of I. Newton’s opinion, but not many. And Cesare Lambroso in his famous book “Genius and Madness” wrote this: “Newton, who conquered all of humanity with his mind, as his contemporaries rightly wrote about him, in his old age also suffered from a real mental disorder, although not as strong as previous men of genius. It was then that he probably wrote “Chronology”, “Apocalypse” and “Letter to Bentel”, works that are vague, confusing and completely different from what he wrote in his younger years" ( C. Lambroso. Genius and madness. - M.: Republic, 1995, p. 63).

This kind of accusation does not correspond to the generally accepted rules of scientific discussion. In those days, as indeed today, they concealed behind themselves an inability to make compelling arguments and argue on the merits.

1.4.NIKOLAY ALEXANDROVICH MOROZOV AS THE FOUNDER OF SYSTEM CHRONOLOGY

ON THE. Morozov is one of the few great encyclopedist scientists in the history of mankind. In 1945 there were three honorary academicians of the USSR Academy of Sciences - N.F. Gamaleya, N.A. Morozov and I.V. Stalin. Fundamental hypothesis of N.A. Morozov’s idea of the artificially extended chronology of antiquity is based on the “repetitions” he discovered, that is, texts that probably describe the same events, but dated different years. ON THE. Morozov was the first scientist to understand that events not only of ancient but also of medieval history needed re-dating, although he did not revise the chronology “above” the 6th century AD. e. Apparently, N.A. Morozov did not know about the similar works of I. Newton and E. Johnson, but what is even more interesting is that many of the conclusions of these chronology researchers coincide.

ON THE. Morozov (1854–1946) - an outstanding Russian encyclopedist scientist (Fig. 1–2). He became the first researcher to truly broadly and radically raise the question of the scientific justification of the chronology accepted today. Known for his work in the field of astronomical, meteorological, physical and chemical problems. Honored Scientist of the RSFSR. Honorary member of the Moscow Society of Natural Scientists. Permanent member of the French Astronomical Society (Societe Astronomique de France). Permanent member of the British Astronomical Association. Since 1922, he has been an honorary member of the Russian Academy of Sciences (since 1925 - the USSR Academy of Sciences), a holder of orders of the USSR. The official reference book of the USSR Academy of Sciences, published in 1945, lists all honorary academicians of the USSR Academy of Sciences for 1945. There are only three of them. This is N.F. Gamaleya, N.A. Morozov and I.V. Stalin.

Rice. 1–2. Portrait of N.A. Morozova.

Fate N.A. Morozova's life was not easy. However, this is the lot of almost any great encyclopedist scientist, of whom there have been not so many in the history of mankind. All these people - for their ability and desire to systematically engage in a variety of sciences - have always caused irritation and criticism from narrow specialists.

Morozov's father, Pyotr Alekseevich Shchepochkin, was a wealthy landowner and belonged to an old noble family. Great-grandfather N.A. Morozova was related to Peter 1. The mother of the outstanding scientist was a simple serf peasant Anna Vasilyevna Morozova. P.A. Shchepochkin married A.V. Morozova, having previously given her her freedom, but without consolidating the marriage in the church, so the children bore their mother’s surname.

At twenty years old N.A. Morozov became a revolutionary-People's Will. In 1881, for revolutionary activities, he was sentenced to indefinite imprisonment in the Shlisselburg fortress, where he independently studied chemistry, physics, astronomy, mathematics, and history. In 1905 he was released after being imprisoned for 25 years. After his release, he was actively engaged in scientific and scientific-pedagogical activities. After the October Revolution, he became director of the Lesgaft Natural Science Institute. After N.A. left Morozov from the post of director, the institute was completely reformed.

It was at his institute that N.A. Morozov and his colleagues carried out most of their famous research on ancient chronology, based on the methods of natural sciences.

Back in 1907 N.A. Morozov published the book “Revelation in a Thunderstorm and Storm,” where he analyzed the dating of the “Apocalypse” and came to conclusions that contradict Scaligerian chronology. In 1914, he published the book “Prophets,” in which, based on astronomical dating techniques, the Scaligerian dating of biblical prophecies was radically revised. In 1924–1932 N.A. Morozov published the fundamental seven-volume work “Christ” (Fig. 1–3). The original title of this work was “The History of Human Culture in Natural Scientific Light.” In it N.A. Morozov presented a detailed critique of Scaligerian chronology. An important fact discovered by him is the unfoundedness of the concept underlying the Scaligerian chronology accepted today.

Having analyzed a huge amount of material, N.A. Morozov put forward and partially substantiated the fundamental hypothesis that the Scaligerian chronology of antiquity is artificially stretched and lengthened in comparison with real events. This hypothesis of N.A. Morozov is based on the “repeats” he discovered, that is, texts that probably describe the same events, but then dated from different years. The publication of this work caused lively controversy in the press, echoes of which are also present in modern literature. Some fair objections were raised, but on the whole the critical part of Christ's work could not be challenged. Apparently, N.A. Morozov did not know about the similar works of I. Newton and E. Johnson, which were practically forgotten by his time. What is even more interesting is that many of the conclusions of N.A. Morozov are in good agreement with the results of Western scientists.

ON THE. Morozov significantly advanced the issue, extending critical analysis up to the 6th century AD. e. and discovering here too the need for radical re-datings. Despite the fact that N.A. Morozov also failed to identify any system in the chaos of these re-datings; his research is at a qualitatively higher level than the analysis of I. Newton.

ON THE. Morozov was the first scientist to understand that events not only of ancient history, but also of medieval history, needed re-dating. Nevertheless, N.A. Morozov did not go beyond the 6th century AD. e., considering that the version of chronology accepted today is more or less correct. We will see later that this opinion of his turned out to be deeply erroneous.

Thus, this is not the first time that questions about revising views on traditional chronology have been raised. Century after century they arise again and again, and this suggests that the problem really exists. And the fact that changes in the chronology of antiquity, proposed, for example, by I. Newton and N.A. Morozov, - are fundamentally close to each other, testifies: this is where the solution to the problem lies.

1.5. ABOUT ROMAN CHRONOLOGY

Roman chronology plays a decisive role in general chronology. There is a discrepancy of 500 years between the various dates for such an important event as the founding of Rome. The Roman chronicles have not reached us, and we have their retellings in very poor form. The most “reliable” documents of Roman history, upon closer examination, turn out to be forged, fabricated much later. The established traditional version of Roman history has always seemed the most reliable - in the absence of powerful methods for verifying legends - only for lack of a better one.

First of all, the situation with Roman chronology should be described, since, as already noted, it plays a decisive role in general chronology. Widespread criticism of the traditional version of Roman chronology began in the 18th century at the Academy of Inscriptions and Fine Arts, founded in 1701 in Paris. There, in the 20s of the 18th century, a discussion arose about the reliability of the Roman tradition in general (Pouilly, Frere, etc.). The accumulated material served as the basis for even more in-depth criticism in the 19th century.

One of the largest representatives of this scientific trend, called hypercriticism, was the famous historian Theodor Mommsen. He wrote, for example, the following: “Although King Tarquinius II was already of age at the time of his father’s death and reigned thirty-nine years later, nevertheless he ascends the throne as a young man. Pythagoras, who arrived in Italy almost a whole generation before the expulsion of the kings (509 BC), is nevertheless considered by Roman historians to be a friend of the wise Numa (died around 673 BC; here the discrepancy reaches, according to at least 100 years). State ambassadors sent to Syracuse in 262 from the founding of Rome negotiate there with Dionysius the Elder, who ascended the throne eighty-six years later (348 BC).”

The traditional version of Roman chronology rests on shaky foundations. For example, there is a discrepancy of 500 years between different dates for such an important event as the founding of Rome. The fact is that, according to Hellanicus and Damaste (allegedly living in the 4th century BC), later supported by Aristotle, Rome was founded by Aeneas and Odysseus (and named after the Trojan woman Roma). This means that the founding of Rome occurs immediately after the end of the Trojan War, in which both Aeneas and Odysseus were participants. But in the version of traditional chronology accepted today, the Trojan War (supposedly XI-11th century BC). dates back to the founding of Rome (supposedly 8th century BC). for about 500 years.

Several interpretations of this contradiction can be proposed: either Rome was founded 500 years earlier, or the Trojan War occurred 500 years later, or the ancient chroniclers report a deliberate lie that Aeneas and Odysseus founded Rome. By the way, what about Romulus then? Or is “Romulus” simply another name for the same Odysseus? Many questions arise. And the deeper you dig, the more there will be.

By the way, according to another version, the name of the city was given by Rom, the son of Odysseus and Kirke. Does this mean that Rom (or Remus, brother of Romulus) is the son of Odysseus? From the point of view of today's traditional chronology, this is impossible.

The uncertainty of the date of the founding of Rome significantly affects the dating of a large number of documents that count the years “from the founding of Rome (the city).” Such, for example, is the famous “History” of Titus Livy. At the same time, it turns out that “Roman traditional history has come down to us in the works of very few authors: the most solid of these works is, without a doubt, the historical work of Titus Livy.”

In this regard, the opinion of the historian Theodor Mommsen is interesting: “With regard to... the world chronicle, the situation was even worse... The development of archaeological science made it possible to hope that traditional history would be verified using documents and other reliable sources; but this hope was not justified. The more research was done and the deeper it became, the more clearly the difficulties of writing a critical history of Rome became clear.”

Further, Mommsen writes even more harshly about the problems of the reliability of Roman history: “The lies in digital data were systematically carried out by him (Valerius Anziatus) right up to the modern historical period... He (Alexander Polyhistor) set an example of how to put the missing five hundred years from the fall of Troy to the rise of Rome into a chronological connection (remember that according to another chronological version, different from the one accepted today, the fall of Troy occurred immediately before the founding of Rome, and not 500 years earlier) ... and fill this gap with one of those meaningless lists of kings that, unfortunately , were in such use among Egyptian and Greek chroniclers; judging by all the data, it was he who brought into the world the kings of Aventine and Tiberinus and the Albanian family of Silvius, whom later posterity did not fail to provide with their own names, specific terms of reign and, for greater clarity, even portraits.”

Theodor Mommsen was far from the only famous scientist who proposed starting a revision of the most important dates of antiquity. An extensive and very skeptical point of view, which questioned the correctness of the chronology of Ancient Rome and, in general, the reliability of our knowledge about the first five centuries of Roman history, is set out, for example, in the works of Louis de Beaufort and G.K. Lewis.

N. Radzig wrote: “The fact is that the Roman chronicles have not reached us, and therefore we must make all our assumptions on the basis of Roman annalistic historians. But even here... we are faced with great difficulties, of which the main thing is that we have the annalists in a very bad shape.”

It is believed that the Roman fasti kept a chronological annual (weather) record of all officials of the ancient world. These tables seemed to be able to serve as a reliable basis for chronology. However, G. Martynov asks the question: “But how can we reconcile with this the constant disagreements that we encounter in Livy at every step in the names of consuls, moreover, their frequent omission and, in general, complete arbitrariness in the choice of names?.. The facts are riddled with irregularities, which are sometimes impossible to understand. Livy was already aware of the instability of this main basis of his chronology.”

As a result, G. Martynov proposes “to admit that neither Diodorus nor Livy have the correct chronology... We cannot trust the linen books, based on which Lipinius Macrus and Tubero give completely contradictory instructions. The most apparently reliable documents, even those, upon closer examination, turn out to be forged, fabricated much later.”

Thus, the established traditional version of Roman history has always seemed to historians not entirely convincing and was considered the most reliable - in the absence of powerful methods for verifying legends - only for lack of a better one.

1.6. PROBLEMS OF EGYPT CHRONOLOGY

Herodotus's chronology is usually significantly shorter than the traditional one, so the discrepancy can reach more than 1200 years. The difference between the dates of the accession to the throne of Men, the first pharaoh, is 3643 years. Egyptology originated at the beginning of the 19th century.

Many documents from ancient Egypt contradict each other in a chronological sense.

Thus, consistently and coherently presenting the history of Egypt, Herodotus in his famous “History” puts the pharaohs Rampsinitis and Cheops next to each other, calling Cheops the successor of Rampsinitis. A modern commentator confidently corrects Herodotus: “Herodotus confuses the chronology of Egypt: Rampsinitis (Ramses II) is the king of the XIX dynasty (1345–1200 BC), and Cheops is the IV dynasty (2600–2480 BC). )". Thus, the discrepancy with the traditional version reaches more than 1200 years.

In general, Herodotus' chronology of kings often does not correspond to the traditional one. Usually it is significantly “shorter” than the Scaligerian one. For example, immediately after Pharaoh Asihis he places Pharaoh Anisis, that is, he makes a leap from the end of the Fourth Dynasty (c. 2480 BC) to the beginning of Ethiopian rule in Egypt (c. 715 BC).” . This leap is 1800 years.

The choice of any one chronological version from several contradictory ones is not always obvious. This was reflected, for example, in the struggle between the so-called. short and long chronologies of Egypt, unfolding in the 19th century. At present, a short chronology is conventionally accepted, but it also carries deep contradictions that have not yet been resolved.

The famous Egyptologist G. Brugsch wrote: “When the reader’s curiosity stops at the question: can any eras and moments of the history of the pharaohs be considered definitively established chronologically, and when he turns to the tables compiled by different scientists for clarification, he will stop in surprise before the most diverse opinions in the calculations of pharaonic years made by representatives of the newest school. For example, German scientists determine the time of accession to the throne of Men, the first pharaoh:

Boeck dates this event to 5702 BC;

Unger - 5613;

Brugsch - 4455;

Louth - 4157;

Lepsius - 5702;

Bunsen - 3623.

The difference between the extreme conclusions of this series of numbers is astonishing, since it amounts to 2079 years... The most thorough work and research carried out by competent scientists to verify the chronological sequence of the reigns of the pharaohs and the order of change of entire dynasties, have proved at the same time the inevitable necessity of allowing simultaneous and parallel reign, which significantly reduces the amount of time required for dominion over the country of the thirty dynasties of Manetho. Despite all the discoveries in this area of Egyptology, numerical data are still in a very unsatisfactory state.”

Modern tables also estimate the date of Mena's accession differently, suggesting options around 3100, around 3000, etc. The total variation of this date reaches 2700 years. If we take into account the opinions of others, for example, French Egyptologists, the situation becomes even more confusing:

Champollion gives 5867 BC. e.;

Lesueur - 5770 BC e.;

Mariette - 5004 BC e.;

Shaba - 4000 BC e.;

Meyer - 3180 BC e.;

Andrzejewski - 2850 BC. e.;

Wilkinson - 2320 BC e.;

Palmer - 2224 BC e. etc.

The difference between Champollion's dating and Palmer's dating is a whopping 3,643 years.

Moreover. At the end of the 19th century, Chantepie de la Saussay wrote: “Egyptology, thanks to which the darkness that covered Egyptian antiquity was first dispelled, was born only 80 years ago. The results of the research were popularized, one might say, too quickly... Thanks to this, many false views came into use. It is not yet possible to construct an Egyptian chronology.”

An even more complex situation arose around the list of kings compiled by the Sumerian priests. The famous archaeologist L. Woolley wrote about this: “It was a kind of backbone of history, similar to our chronological tables... But, unfortunately, such a list was of little use... The chronology of the list of kings as a whole is clearly meaningless... The sequence of dynasties was established arbitrarily" .

Moreover, the exceptional antiquity attributed today to these lists is inconsistent with modern archaeological evidence. For example, reporting on excavations of royal tombs in Mesopotamia, L. Woolley talks about a series of finds of gold toiletries: “One of the best experts said that these things were Arab work of the 13th century AD. e. And one cannot blame him for such a mistake, because no one suspected that such high art could exist in the 3rd millennium BC.”

Unfortunately, this criticism did not receive constructive development at that time due to the lack at that time of objective methods of a statistical nature that would allow checking previous chronological identifications and establishing dates in an independent and objective manner.

1.7. MERGING OF THE MIDDLE AGES AND ANCIENTITY: TACITES AND POGGIO, CICERO AND BARZIZZZA, VITRIVIUS AND ALBERTIE

The famous ancient Roman “History” of Cornelius Tacitus may have been written by the famous medieval Italian humanist Poggio Bracciolini. Poggio discovered and put into circulation the works of Quintillion, Valerius Flaccus, Asconius Pedianus, Nonius Marcellus, Probus, some treatises by Cicero, Lucretius, Petronius, Plautus, Tertullian, Marcellinus, Calpurnius Secula - but the circumstances of these finds and datings were never explained anywhere manuscripts. The bulk of the manuscripts on which our knowledge of Greek science is based are Byzantine copies produced 500 to 1500 years after the death of their authors. Around 1420, the Milanese professor Gasparino Barzizza took on a risky task: he was going to fill the gaps of Cicero’s “incomplete excerpt” with his own additions for coherence. The far-reaching parallels between the books of the “ancient” Vitruvius and the remarkable humanist of the 15th century Alberti are noteworthy. Different pronunciations and spellings of the same name by different historians of different nationalities seem to have repeatedly been the cause of large and small chronological errors. One gets the feeling that the architects of the 14th–15th centuries did not at all consider their work to be “imitation of antiquity,” but simply created it.

Of key interest is the question of the origin of ancient primary sources. It is known that the vast majority of these documents only surfaced during the Renaissance after the Dark Ages. The appearance of manuscripts often took place in an environment that was not conducive to a critical analysis of their dating.

Famous historians Gochard and Ross published studies in 1882–1885 and in 1878 in which they proved that the famous ancient Roman “History” of Cornelius Tacitus actually belongs to the pen of the famous Italian humanist Poggio Bracciolini. The history of the discovery of the books of K. Tacitus really raises many questions. It was Poggio who discovered and put into circulation the works of Quintillian, Valerius Flaccus, Asconius Pedianus, Nonius Marcellus, Probus, some treatises of Cicero, Lucretius, Petronius, Plautus, Tertullian, Marcellinus, Calpurnius Secula, etc. The circumstances of these finds and dating of manuscripts.

In the 15th century, famous humanists Manuel Chrysolor, Gemist Pleton, Vissarion of Nicea and others came to Italy. They first introduced Europe to the achievements of “ancient Greek thought.” Byzantium at this time gave the West almost all of the ancient Greek manuscripts known today from ancient times. Otto Neugebauer wrote: “Most of the manuscripts on which our knowledge of Greek science is based are Byzantine copies produced 500 to 1500 years after the death of their authors.”

An objective analysis of classical ancient texts indicates the uncertainty of their origin and the lack of documented data about their fate in the previous, so-called “Dark Ages”. This leads in many cases to assume the absence of these texts before the eve of the Renaissance.

Thus, the oldest copies of the so-called incomplete translation of Cicero’s texts are considered to be those of the 9th–10th centuries AD. e., however, the most ancient manuscript of an incomplete copy perished long ago. In the 14th–15th centuries, interest in Cicero grew, and it came to the point that around 1420, the Milanese professor Gasparino Barzizza took on risky work: he was going to fill in the gaps of the “incomplete excerpt” with his own additions for coherence (!). But before he could finish his work, a miracle happened.

In the remote Italian town of Lodi, an abandoned manuscript was found with the full text of all the rhetorical works of Cicero... Barzizza and his students pounce on the new find, with difficulty decipher its ancient (probably 13th century) font and finally make a readable copy. Lists are taken from this copy, and in their totality they constitute a “complete excerpt”... Meanwhile, the irreparable happens: the archetype of this excerpt, the Lodi manuscript, turns out to be abandoned, no one wants to struggle with its difficult text, it is sent back to Lodi. And there she disappears without a trace, so that since 1428 nothing is known about her fate. European philologists still mourn this loss.

The famous book of Suetonius “The Lives of the Twelve Caesars” is also available only in very late copies. They all go back to a single ancient manuscript that was allegedly in Einhard’s possession; allegedly around 818 AD. e. Einhard, creating his “Life of Charles,” carefully reproduced, as is considered today, “Suetonian biographical schemes.” This is the so-called “Fulda manuscript”, and the first copies from it have not reached us. The oldest copy of Suetonius's book is considered to be a text from the 9th century AD. e., but it surfaced only in the 16th century. The remaining lists are dated in traditional history no earlier than the 11th century AD. e.

The dating of ancient sources was carried out in the 15th–16th centuries on the basis of considerations that have not reached us. Only in 1497 was the book “On Architecture” by Vitruvius opened. According to N.A. Morozov, in the astronomical section of Vitruvius’ book, the periods of heliocentric (!) revolutions of the planets are indicated with incredible accuracy. The architect Vitruvius, who allegedly lived in the 1st–2nd centuries AD. e., knew these numbers better than the astronomer Copernicus! Moreover, in the orbital period of Saturn he was mistaken by only 0.00007 fraction of the modern value of the period, of Mars by 0.006, and of Jupiter by 0.003.

It is worth paying attention to the far-reaching parallels between the books of the “ancient” Vitruvius and the remarkable humanist of the 15th century Alberti. It is worth noting some consonance between the names of Alberti and Vitruvius, based on the frequent transition of “b” to “c” and vice versa: Alb(v)erti - Vitruvius. In general, different pronunciations and spellings of one name by historians of different nationalities, apparently, have repeatedly been the cause of large and small chronological errors. Alberti (1414–1472) is known as a major architect, the author of a fundamental architectural theory, extremely similar to the similar theory of the “ancient” Vitruvius. Like the “ancient” Vitruvius, Alberti wrote a large work that included not only the theory of architecture, but also information on mathematics, optics, and mechanics.

The title of Alberti’s medieval work “Ten Books on Architecture” coincides with the title of a similar “ancient” work by Vitruvius. It is believed that the “ancient” Vitruvius was for the medieval Alberti “a role model when drawing up his own treatise.” Alberti's work is entirely designed in “ancient tones.” Experts have long compiled tables in which fragments of the works of Alberti and Vitruvius appear parallel to each other (sometimes coinciding literally!). Historians comment on this circumstance as follows: “All these numerous parallels... reveal the Hellenistic-Roman atmosphere in which his own thoughts were formed.”

Thus, the book of the “ancient” Vitruvius fits absolutely naturally into the medieval atmosphere and ideology of the 15th century AD. e. Moreover, the vast majority of Alberti’s medieval buildings were made, it turns out, “in the antique style.” In particular, he creates a palace “in the image and likeness of a Roman amphitheater.” As a result, the leading architect of the medieval era fills the cities of Italy with “ancient” buildings that are now - but by no means in the 15th century AD. e. - are considered “imitations of antiquity.” He writes books “in the ancient style,” not suspecting that they will later be declared “an imitation of antiquity.” And only after all this, in 1497 AD. e., the book of the “ancient architect Vitruvius” will be opened, sometimes almost word for word coinciding with a similar book by the medieval Alberti.

One gets the feeling that the architects of the 14th–15th centuries did not at all consider their work to be “imitation of antiquity,” but simply created it. The theory of “imitation” will appear much later, in the works of Scaligerian historians.

1.8. MEASURING AND LEAPING TIME IN THE MIDDLE AGES

Until the 13th–14th centuries, instruments for measuring time were a rarity, a luxury item. Augustine equated each day of creation to a millennium and tried to use such reasoning to determine the duration of human history. The crusaders at the end of the 11th century were convinced that they were punishing not the descendants of the Savior’s executioners, but these executioners themselves. Petrarch participated in the discussion about the falsity of the privileges given by Caesar and Nero to the Austrian ducal house in the 13th century AD. e. Gladiatorial fights in the Middle Ages, as in “antiquity,” ended in the death of the fighter.

An analysis of ancient documents shows that previous ideas about time were sharply different from modern ones. Until the 13th–14th centuries, instruments for measuring time were a rarity, a luxury item. Common clocks in medieval Europe were sun clocks, sand clocks, and clepsydra water clocks. But sundials were only suitable in clear weather, and clepsydras remained rare.

At the end of the 9th century AD. e. Candles were widely used to keep time. For example, when traveling, King Alfred of England took candles of equal length with him and ordered them to be burned one after another. The same counting of time was used back in the 13th–14th centuries, for example, under Charles V. The monks were guided by the number of pages of sacred books they read or psalms that they managed to say between two observations of the sky.

But for informative astronomical observations you need a watch with a second hand! But even after the invention and spread of mechanical watches in Europe, for a very long time they did not have not only a second hand, but also a minute hand.

The problem of inaccurate measurement of real time in the Middle Ages is complemented by the most sophisticated chronological Kabbalah. In particular, periods of time acquire a completely different duration when used to measure biblical events... Thus, Augustine equated each day of creation to a millennium (!) and tried to use such reasoning to determine the duration of human history.

It's funny that in the Middle Ages the past is depicted in the same categories as the present. Biblical and ancient characters appear in medieval costumes. The juxtaposition of Old Testament kings and patriarchs on the portals of cathedrals with ancient sages and gospel characters best reveals the anachronistic attitude towards history. The crusaders at the end of the 11th century were convinced that they were punishing not the descendants of the Savior’s executioners, but these executioners themselves. This fact is quite significant.

Modern historians, based on Scaligerian chronology, believe that the Middle Ages confused eras and concepts on a grand scale, that medieval authors only “out of their ignorance” identified the ancient, ancient, biblical era with the era of the Middle Ages. But, besides this explanation, another point of view is quite reasonable. It can be assumed that these statements of medieval chroniclers correspond to reality, and we now consider them “anachronisms” because today we follow the incorrect Scaligerian chronology.

Scaliger's chronological version reflects only one of several medieval chronological concepts. Along with it, there were other versions. For example, it was believed that the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation of the 10th–13th centuries AD. e. is a direct continuation of the Roman Empire, which supposedly fell in the 6th century AD. e. according to the Scaligerian version.

Here we can mention a medieval dispute that is strange from a modern point of view. The great Italian poet and founder of the humanistic culture of the Renaissance, Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374), based on a number of philological and psychological observations, argued that the privileges given by Caesar and Nero to the Austrian ducal house (in the 13th century AD!) were false. For a modern historian, the very idea that the “ancient” Caesar and Nero were contemporaries of the medieval Austrian ducal house (which began to rule only in 1273 AD, that is, sort of 1200 years after Caesar and Nero), is, of course, absurd. But, as we see, Petrarch’s medieval opponents in the 14th century did not think so at all. e. Then it still had to be proven!

Regarding these famous documents, E. Priester notes: “All interested parties understood perfectly well that these were obvious and unscrupulous forgeries, and yet they “politely” turned a blind eye to this circumstance.”

Another striking example. Modern people from school are accustomed to the idea that famous gladiatorial fights took place only in the “distant ancient past.” But that's not true. V. Klassovsky, having talked about gladiator fights in “ancient” Rome, immediately adds that these fights also took place in medieval Europe of the 14th century AD. e.! For example, he points to gladiator fights in Naples around 1344 AD. e. These medieval battles, as in “antiquity,” ended in the death of the fighter.

1.9. DATING OF BIBLE TEXTS

All three of the oldest texts of the Bible appeared only after the 15th century AD. e. The most ancient surviving manuscripts of the Bible are written in Greek, and there are no Hebrew manuscripts of the Bible earlier than the 9th century AD. e. does not exist. The vast majority of dating of biblical manuscripts is based on “handwriting style,” which makes this “dating” completely dependent on Scaligerian chronology. The canon (the establishment of the law by the Christian Church) of the Bible was actually established only from the time of the new Council of Trent in the 16th century AD. e.

The chronology of biblical books and their dating is very uncertain and rests on the authority of theologians and historians of modern times.

The oldest surviving more or less complete copies of the Bible are the Alexandrian, Vatican and Sinai manuscripts. All three manuscripts are dated paleographically (that is, based on “handwriting style”) to the second half of the 4th century. n. e. The language of the codes is Greek. The least is known about the Vatican Codex - in particular, it is not clear how and where this monument came from around 1475 to the Vatican... It is known about the Alexandrian Codex that in 1628 Patriarch Cyril Lucaris donated it to the English king Charles I. The Sinaiticus Codex was only discovered in the 19th century by K. Tischendorf.

Thus, all three of the oldest Bible codes appeared only after the 15th century AD. e. The reputation of the antiquity of these documents was created by the authority of K. Tischendorf, who was based on the “style of handwriting.” However, the very idea of paleographic dating presupposes the already known global chronology of other documents, and therefore is not an independent method of dating.

Of the individual biblical works, the oldest are considered to be the manuscript of the prophecy of Zechariah and the manuscript of Malachi, dating back to the 6th century AD. e., and they are also dated paleographically. The most ancient surviving manuscripts of the Bible are written in Greek. No Hebrew Bible manuscripts before the 9th century AD. e. (!) does not exist. Although the manuscripts are of a later date, mainly from the middle of the 13th century AD. e., are stored in many national book depositories. The oldest Hebrew manuscript containing the complete Old Testament Bible dates back to 1008 AD. e.

It is assumed that the canon (the establishment of law by the Christian church) of the Bible was established by the Council of Laodicea in 363 AD. e., however, no acts of this and other early councils have survived. In reality, the canon was officially established only from the time of the new Council of Trent, convened during the Reformation in 1545 and lasting until 1563. By order of this council, a large number of books considered apocryphal were destroyed, in particular the Chronicles of the Kings of Judah and Israel. It is significant that the overwhelming majority of dating of biblical manuscripts is based on paleography, which makes this “dating” completely dependent on Scaligerian chronology. When the chronology changes, all “palaeographic dating” automatically changes.

For example, in 1902, the Englishman Nash acquired in Egypt a fragment of a papyrus Hebrew manuscript, the dating of which scientists could not come to a consensus on. Finally, we agreed to consider that the text dates back to the beginning of the century. e. Subsequently, after the discovery of the Qumran manuscripts, it was the comparison of the “handwriting” of the Nash papyrus and the Qumran manuscripts that made it possible from the very beginning to establish the great antiquity of the latter. Thus, one piece of papyrus, about the dating of which they cannot come to a consensus, drags down with it a whole mass of other documents.

It is not surprising that when dating the Qumran scrolls, great disagreement arose among scientists - from the 2nd century BC. e. until the time of the Crusades. For example, the American historian S. Tseitlin categorically insists on the medieval origin of these texts.

1.10. READING A TEXT WRITTEN WITH CONSONANTS ALONE IS A VOLUTION PROBLEM

Many original texts in a wide variety of languages do not have vowels, which creates problems in reading and interpreting them. The Russian “KRV” can mean: blood, curve, blood, cow, etc. Vowel letters were introduced into the Hebrew Bible no earlier than the 7th or 8th centuries AD. The problem of vocalization played a key role in the ambiguities of ancient texts that arise when interpreting the names of cities, countries, names of kings, etc.

Many original texts in a wide variety of languages do not have vowels, which creates problems in reading and interpreting them. Since the Hebrew written language originally had neither vowels nor signs replacing them, the books of the Old Testament were written using only consonants.

Ancient Egyptian texts were also written using consonants. The names of Egyptian kings are given in modern literature in a conventional, so-called school transmission, adopted in textbooks... This transmission often varies significantly, and the reading is quite arbitrary.

Probably, the rarity and high cost of writing materials in ancient times forced scribes to save material by discarding vowels when writing. And the very manner of oral speech in terms of pronouncing vowels and consonants in the old days, apparently, differed significantly from the modern one. To some extent, this manner can be understood from the speech of modern tribes, who rarely use written texts in communication.

True, if we now take the Hebrew Bible or manuscript, we will find in them signs indicating the missing vowels. These signs did not belong to the Hebrew Bible. The books were read one consonant at a time, filling in the gaps with vowels to the best of one’s ability and in accordance with the apparent requirements of the meaning and oral traditions.

Imagine how accurate a letter written with only consonants can be!

T.F. Curtis wrote: “Even for the priests, the meaning of the writings remained extremely doubtful and could only be understood with the help of the authority of tradition.” It is assumed that this serious defect in the Hebrew Bible was eliminated no earlier than the 7th or 88th centuries AD, when the Massorites (Massorites) revised the Bible and “added ... signs to replace vowels; but they had no guidance except their own judgment and very imperfect tradition.”

Driver adds: “From the time of... the Massorites in the 7th and 8th centuries... the Jews began to guard their sacred books with extraordinary care even when it was too late to correct... the damage done to them. The result of this care was only the perpetuation of distortions, which were now placed in terms of authority... completely on the same level as the original text.”

It was previously believed that vowels were introduced into the Hebrew text by Ezra in the 5th century BC. e. When, in the 16th and 17th centuries, Levita and Capellus in France refuted this opinion and proved that vowel signs were introduced only by the Massorites, this discovery created a sensation throughout Protestant Europe. It seemed to many that the new theory led to the complete overthrow of religion. If vowel signs were not a matter of divine revelation, but were only a human invention, and, moreover, of a much later time, then how could one rely on the text of Scripture? The debate aroused by this discovery was one of the most heated in the history of new biblical criticism and lasted more than a century. Finally they stopped: the correctness of the new view was recognized by everyone.

It seems that the problem of vocalization played a key role in the ambiguities of ancient texts that arise when interpreting the names of cities, countries, names of kings, etc. Tens and hundreds of different variants of vocalization of the same term appear. As a result, Scaligerian history does not always identify unambiguous biblical inconsistent names of cities, countries, etc., based on Scaliger’s chronology and from a hypothetical localization that attributes biblical events exclusively to the Middle East.

1.11. PROBLEMS OF GEOGRAPHICAL LOCALIZATION OF ANCIENT EVENTS

None of the books of the Old and New Testaments have reliable archaeological evidence for their traditional geographical and temporal localization. Perhaps in the Middle Ages the same famous city on the Bosphorus was called by different names: Troy, New Rome, Constantinople, Jerusalem. Southern Italy in the Middle Ages was sometimes called Magna Graecia. Herodotus's map may be inverted in relation to the modern one, that is, with the replacement of east by west. According to the version of modern historians, we have to assume that Herodotus identifies the following bodies of water: Red Sea - South Sea - Black Sea - North Sea - Mediterranean Sea - Persian Gulf - Our Sea - Indian Ocean.

The famous archaeologist L. Wright, by the way, an ardent supporter of the Scaligerian localization and dating of biblical events, wrote: “The vast majority of finds prove nothing and disprove nothing; they fill the background and provide the setting for the story... Unfortunately, the desire to "prove" the Bible permeates many of the works available to the average reader. The evidence is misused, the conclusions drawn from it are often incorrect, erroneous or half correct.”

A careful analysis of specific facts shows that none of the books of the Old Testament has reliable archaeological evidence of their traditional geographical and temporal localization. The entire “Mesopotamian” theory of the Bible is called into question.

The situation is no better with the traditional localization of the events of the New Testament, which supposedly took place near modern Jerusalem. The historians themselves frankly write: “Reading the literature devoted to the archeology of the New Testament makes a strange impression. There are tens and hundreds of pages of descriptions of how the excavations were organized, what the appearance of the relevant areas and objects is, what the historical and biblical “background” of this plot is, and in conclusion, when it comes to reporting the results of all the work, there are several vague and clearly confused phrases that the problem has not yet been solved, but there is hope that in the future, etc. We can say with complete confidence and categoricalness that not a single, literally not a single New Testament plot has so far had any convincing archaeological confirmation... Not a single place that is traditionally considered the scene of one or another New Testament event can be indicated with the slightest degree of certainty.”

Indeed, significant difficulties accompany attempts to correctly geographically localize many ancient events. For example, “New City” is present in ancient chronicles in several copies:

Naples in Italy, which still exists today;

Carthage, which also means “New City”;

Naples in Palestine;

Scythian Naples;

New Rome, that is, Constantinople, Constantinople, could also be called the New City.

Therefore, when some chronicle tells about events in a certain “Naples”, you should carefully figure out which city you are talking about.

Let's take another example - Troy.

One of the localizations of the famous Homeric Troy is near the Hellespont (for which, however, there are also several significantly different localizations). It was precisely based on this hypothesis - that the ruins of Troy were located near the Hellespont - that G. Schliemann in the 19th century assigned, without any serious grounds, the high-profile name of Troy to the meager settlement he found in the Hellespont region.

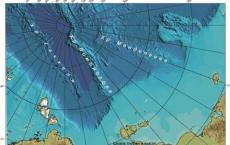

In traditional chronology, it is believed that Homeric Troy was finally destroyed in the 12th–13th centuries BC. e. But in the Middle Ages, for example, the Italian Troy, which, by the way, exists to this day, enjoyed well-deserved fame. This medieval city played an important role in many medieval wars, especially in the famous war of the 13th century AD. e. Byzantine medieval historians, for example, Niketas Choniates and Nikephoros Gregoras, also speak of Troy as an existing city. Titus Livius indicates the place “Troy” and the Trojan region in Italy (Fig. 1-3a).

Rice. 1-For. Ancient miniature “At the Gates of Troy”

Some medieval historians identify Troy with Jerusalem. This confuses modern commentators: “And the book of Homer itself somewhat unexpectedly turned ... into a book about the destruction of Jerusalem from beginning to end.” The medieval author Anna Comnena, speaking about Ithaca, the birthplace of Homer’s Odysseus, one of the main heroes of the Trojan War, unexpectedly declares that on the island of Ithaca “a large city was built, called Jerusalem.” It should be recalled here that modern Jerusalem is not located on an island.

The second name of Troy is Ilion, and the second name of Jerusalem is Elia Capitolina. There is an analogy: Elia - Ilion. Perhaps, in the Middle Ages, it was true that some people called the same city Troy-Ilion, and others called Jerusalem-Elia? Eusebius Pamphilus wrote: “He called the small cities of Phrygia, Petusa and Timion, Jerusalem.” The above facts show that the name Troy “multiplied” in the Middle Ages and was applied to different cities. Perhaps there was originally a single medieval “original”? In this regard, one cannot help but pay attention to the following data preserved in Scaligerian history and allowing us to put forward the hypothesis that in some documents Homer's Troy is probably the famous city of Constantinople, Tsar-Grad.

It turns out that the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great, when founding New Rome, the future Constantinople, met the wishes of his fellow citizens and “first chose the site of ancient Ilion, the fatherland of the first founders of Rome.” The famous historian Jelal Essad reports this in his book “Constantinople” (M., 1919, p. 25). But Ilion, as is well known from Scaligerian history, is another name for Troy. As historians further say, Constantine nevertheless “changed his mind,” shifted the new capital slightly to the side and founded New Rome nearby, in the city of Byzantium.

Perhaps in the Middle Ages the same famous city on the Bosphorus was called by different names: Troy, New Rome, Constantinople, Jerusalem? After all, the name “Naples” simply translates as “New City”. Maybe New Rome was once also called the New City, that is, Naples? Let us also note that the south of Italy in the Middle Ages was called Magna Graecia.

Today it is believed that the city of Babylon was located in modern Mesopotamia. The authors of some medieval texts hold a different opinion. For example, the book Serbian Alexandria places Babylon in Egypt. Moreover, it localizes the death of Alexander the Great in Egypt. But according to the Scaligerian version, Alexander the Great died in Mesopotamia. Moreover, it turns out: “Babylon is the Greek name for the settlement located opposite the pyramids (Tower of Babel?). In the Middle Ages, this was sometimes called Cairo, of which this settlement became a suburb.” The term "Babylon" has a meaningful translation, like many other city names. Therefore, this term could be applied to different cities.

Eusebius reports that Rome was called Babylon. Moreover, “by Babylon, Byzantine historians (in the Middle Ages) most often mean Baghdad.” A medieval author of the 11th century AD speaks about Babylon as an existing, and not at all destroyed, city. e. Mikhail Psell.

The significance of Herodotus for Scaligerian history is enormous. But now he declares that the Nile flows parallel to the Istru, which is now identified with the Danube (and for some reason not with the Dniester, for example). And here it turns out that the opinion about the parallelism of the Danube and the Nile was widespread in medieval Europe until the end of the 13th century AD. e.

The identification of Herodotus's geographical data with a modern map encounters significant difficulties within the framework of the Scaligerian localization of the events he describes. In particular, the numerous corrections that modern historians are forced to make when making such identifications show that Herodotus's map may be inverted in relation to the modern one, replacing east with west. This orientation is typical of many medieval maps.

Commentators are forced to believe that in different places in Herodotus’ History the same names of seas mean completely different bodies of water. For example, according to modern historians, we have to assume that Herodotus identifies the following bodies of water: Red Sea - South Sea - Black Sea - North Sea - Mediterranean Sea - Persian Gulf - Our Sea - Indian Ocean. Many strange things arise from an unbiased analysis of the geography of the Bible.

1.12. ANALYSIS OF BIBLE GEOGRAPHY

Many biblical texts explicitly describe volcanic phenomena. The attribution of these descriptions to the traditional Mount Sinai and to Jerusalem in Palestine is strange: this mountain was never a volcano. The only powerful volcano in the Mediterranean is Vesuvius. It is possible that some of the events described in the Bible, namely the campaign of the Israelites led by Moses and the subsequent conquest of the “Promised Land” led by Joshua, took place not in modern Palestine, but in Europe, in particular in Italy.

Very often, ancient events are effectively and colorfully shaded by grandiose natural phenomena. The fact that many biblical texts explicitly describe volcanic phenomena has been noted in history for a long time. The Bible says: “And the Thunderer said to Moses: Behold, I will come to you in a thick cloud... to Mount Sinai... during the lingering sound of the trumpet, (when the cloud departs from the mountain), they (the people) may ascend the mountain... There were thunder and lightning , and a thick cloud over Mount (Sinai), and a very strong trumpet sound... Mount Sinai was all smoking because the Thunderer had descended on it in fire; and smoke rose from it like smoke from a furnace, and the whole mountain shook greatly; and the sound of the trumpet grew stronger and stronger" (Exodus, XIX). And further: “All the people saw thunder and flames, and the sound of a trumpet, and a smoking mountain” (Exodus, XX). “You stood... at Horeb... and the mountain burned with fire to the very heavens, and there was darkness, cloud and darkness” (Deuteronomy, IV, 9-12).

The destruction of the biblical cities of Sodom and Gomorrah has long been considered in history as destruction as a result of a volcanic eruption: “And the Thunderer rained brimstone and fire on Sodom and Gomorrah ... behold, smoke rises from the earth like the smoke of a furnace” (Genesis, XIX, 24, 28). Etc.

Here is a list of “volcanisms” in the Bible compiled by V.P. Fomenko and T.G. Fomenko: Genesis (XIX, 18, 24), Exodus (XIII, 21, 22), (XIV, 18), (XX, 15), (XXIV, 15, 16, 17), Numbers (XIV, 14), ( XXI, 28), (XXVI, 10), Deuteronomy (IV, 1 1, 36), (V, 19, 20, 21), (IX, 15, 21), (X, 4), (XXXII, 22) , 2nd book. Kings (XXII, 8-10, 13), 3rd book. Kings (XVIII, 38, 39), (XIX, 11,12), 2nd book. Kings (I, 10–12, 14), Nehemiah (IX, 12, 19), bk. Psalms (ps. II, v. 6, ps. 106, v. 17), (ps. 106, v. 18), Ezekiel (XXXVIII, 22), Jeremiah (XLVIII, 45), Lamentations of Jeremiah (II, 3) , (IV, 1 1), Isaiah (IV, 5), (V, 25), (IX, 17, 18), (X, 17), (XXX, 30), Joel (II, 3, 5, 10 ).

The attribution of these descriptions to the traditional Mount Sinai and to Jerusalem in Palestine is at least strange: this mountain was never a volcano. So where did the events take place? It is enough to study the geological map of the surroundings of the Mediterranean. There is not a single active volcano in the Sinai Peninsula, Syria and Palestine. There are only zones of “Tertiary and Quaternary volcanism”, as, for example, near Paris. In historical time, i.e. after the beginning of the century. e., no volcanic phenomena have been recorded here.

The only powerful volcanic zones still active in the region are Italy and Sicily. Egypt and North Africa do not have volcanoes. So, you need to find:

1) a powerful volcano that was active during the historical era;

2) near the volcano - the destroyed capital (see Lamentations of Jeremiah);

3) near the volcano - two more cities destroyed by it: Sodom and Gomorrah.

There is only one such volcano in the Mediterranean. This is Vesuvius, one of the most powerful volcanoes active in historical times. At its foot is the famous Pompeii (the capital?) destroyed by the eruption and two destroyed cities: Stabia (Sodom?) and Herculaneum (Gomorrah?). It should be noted that there are some similarities in the names.

ON THE. Morozov conducted an interesting analysis that allows us to read the unspoken text of some fragments of the Bible, taking into account the location of Mount Sinai-Horeb-Zion in Italy. Let us give some examples (translation from Hebrew by N.A. Morozov).

The Bible says: “He spoke to us on Mount Horeb... “It is enough for you to live on this mountain!” (...) set out on your journey... to the land of KNUN" (Deuteronomy I, 7). Theologians pronounce “KNUN” as “Canaan” and refer it to the desert on the shores of the Dead Lake, but another vowel is also possible: “KNUN” - “Kenua” instead of “Genoa” (that is, the Genoese region in Italy). The Bible says: “To the land of Canaan, and to LBUN” (Deuteronomy I, 7). LBNUN theologians pronounce Lebanon, but LBNUN often means “white” - the same as “Mont Blanc” - “White Mountain”.