Acmeism. "Shop of poets". Basic ethical and aesthetic attitudes. Creativity of poets who emerged from acmeism. N.S. Gumilev. The emergence of the "shop of poets" Literary association shop of poets

"Workshop of poets" is the name of various literary circles and associations of the 1910-30s. The first, main, and most famous "Workshop of Poets" was created by N.S. Gumilyov with the participation of S.M. Gorodetsky in St. Petersburg in the autumn of 1911. There were several reasons: Gumilyov's quarrel with Vyach. Ivanov in the spring of 1911, disappointment in symbolism, which was in crisis, a constant desire not only to participate in the literary process, but to organize and manage it, the desire to oppose the Tower of Vyach. Ivanov and the Academy of Verse with his own poetic association, in which the leading role would belong to Gumilyov. At first, the Workshop of Poets was conceived as a “non-partisan” one, uniting the poets of a generation without taking into account their literary tastes and preferences. The tasks were partly the same as those at the Academy of Verse - literary communication, professional analysis of the work of members of the "Poets' Workshop", honing skills. But the center of literary life at the same time moved from the Tower to the "Workshop of Poets".

At the first meeting of the "Workshop of Poets", held on October 20, 1911 at Gorodetsky’s apartment, there were, in addition to future acmeists and literary youth, poets of various directions, incl. and famous: A. Blok, N. Klyuev, M. Kuzmin, A. N. Tolstoy, V. Pyast and others; some of them soon stopped attending meetings.

Meetings of the Poets' Workshop were held at Gorodetsky, at the Gumilyovs in Tsarskoe Selo, at M.L. Lozinsky's or in the Stray Dog, which soon became a kind of headquarters for the Poets' Workshop. 15 meetings (three per month). From October 1912 to April 1913 - approximately ten meetings (two per month) ”(Akhmatova A). In the last winter of 1913-14 there were probably even fewer meetings. By the middle of 1912, an acmeist core had formed in the “Poets' Workshop”, and although many members of the “Poets' Workshop” close to the acmeists - Lozinsky, Vas. Gippius - did not join acmeism themselves, the Workshop increasingly began to be perceived as a narrow party association. Members of the Poets' Guild were published in the Hyperborea magazine edited by Lozinsky (October 1912 - December 1913; No 19/10), in Apollo, edited by S.K. “The New Journal for All”, at the beginning of 1913 during the period of editorship of V. Narbut, and in 1914-16, when the journal was edited by A.N. Yavorovskaya (Boane). Tastefully designed collections of poems by members of the Poets' Workshop were published under the publishing brand "Hyperborea" or "Poets' Workshop". In 1914-18, several books by members of the Workshop of Poets were published by the Alcyone publishing house.

Many contemporaries - from Vyach. Ivanov and Blok to D. Filosofov and A. Bukhov - greeted the creation of the "Workshop of Poets" disapprovingly, in the press especially many critical reviews appeared in 1913-14. According to Akhmatova’s memoirs, “in the winter of 1913-14 (after the defeat of acmeism), we began to be weary of the workshop and even gave Gorodetsky and Gumilyov a petition drawn up by Osip and myself to close the workshop. Gorodetsky imposed a resolution: “Hang everyone, and imprison Akhmatova” (Akhmatova A. Decree). In the spring, Gorodetsky accused Gumilyov of "deviation from acmeism", and although later both tried to reconcile, "a return to the past was impossible" (Akhmatova A. Autobiographical prose. 1989. No5). In the summer of 1914, the war began, Gumilyov went to the front as a volunteer, and the work of the "Poets' Workshop" came to naught.

The second "Workshop of poets"

In the summer of 1916, GV Adamovich and GV Ivanov decided to revive the "Workshop of Poets". The first meeting was held in Adamovich's apartment on Vereiskaya Street. They gathered once a month at Adamovich’s apartment, and most often in the “Halt of comedians”, which became a kind of headquarters for the new “Workshop of Poets”. Of the senior acmeists, only O.E. invited Narbut and M.A. Zenkevich decided not to join the new "Workshop of Poets".

The composition of the new “Workshop of Poets” included K.V. Mochulsky, A.I. Piotrovsky, V.A. Pyast, S.E. Radlov, A.D. poets”, nor its participants were, and it was conceived more as a secular-salon enterprise than a literary-directed one, therefore, by the autumn of 1917, it completely collapsed.

The third "Workshop of poets"

The third "Workshop of Poets" (also often referred to in the literature as the Second) was created in the autumn of 1920 returned from England Gumilyov. “Initially, only Gumilyov, Georgy Ivanov, Georgy Adamovich, Nikolai Otsup and Vsevolod Rozhdestvensky were members of the New Workshop. Then Irina Odoevtseva was accepted to replace the exiled Vsevolod Rozhdestvensky. By the beginning of the 21st year, S. Neldikhen and Konstantin Vaginov became members of the "Workshop". But the real headquarters was not the whole "Workshop", but only four: Gumilyov, Ivanov, Adamovich and Odoevtseva. The rest were not friends, but "necessity" (Chukovsky N. Literary memories, 1989). In addition to the named names, the meetings of the "Workshop of Poets" were also attended by Mandelstam, L. Lipavsky, P. Volkov, and V. Khodasevich, who did not immediately understand the Gumipev literary policy. The third "Poets' Workshop" was no longer so much a poetic studio as the first, or a salon like the second, but a literary group with iron discipline. Rozhdestvensky later recalled: “Participants of the former Guild were called “masters”, and its head was “syndic”. They met regularly on a certain day of the week, new poems were analyzed in detail "to the accuracy of a single line, to a single word", nothing could be printed or read in public speeches without general approval. In some cases, mandatory revision was required. The composition of individual collections was compiled collectively. Negotiations with publishers were conducted in the same manner. Strong friendship and mutual support were obligatory” (Nikolai Gumilyov: Research. Materials. Bibliography, 1994). The workshop organized poetry evenings in the House of Arts, published a handwritten, then hectographed almanac "New Hyperborea" and handwritten collections of poems, and from March 1921 began to print real collections of poems and almanacs. The work of the "Workshop of Poets" still caused a lot of polemical reviews and assessments, but more and more criticism in the literal party sense (L. Trotsky, G. Adonts). Mochulsky briefly summarized the history of the third Poet Workshop in his article: “In 1920, a new workshop appeared and immediately became the center of the poetic life of St. Petersburg… meetings take place three times a month… The work of the workshop is lively, often stormy.. The dogmatist Gumilyov has to fight not only with sharp criticism from outside, but also with stubborn opposition from within ... By the autumn of 21, the main - the classical core of the group was finally determined. After the death of Gumilyov, the workshop somehow shrinks. G. Ivanov becomes its head; the symbolist Lozinsky and the vers librist Neldichen leave. Decided not to accept new members. The desire for unity both in theory and in poetic practice leads to the creation of a critical department in the collections of the workshop ”(K. Mochulsky. The New Petrograd Workshop of Poets Last news. 1922. Dec. 2). Adamovich became the leading critic and ideologist of the Poets' Guild. The surviving members of the workshop prepared for publication a posthumous collection of poems by Gumilyov and his Letters on Russian Poetry (1923), published their collections, after which in the second half of 1922 the entire central core of the Workshop of Poets went into exile.

But the history of the “Workshop of Poets” did not end there. At least four of his staunch adherents - Adamovich, G. Ivanov, Odoevtseva and N. Otsup - considered themselves the successors of Gumilev's work, and the seasons of the Poets' Workshop that they reopened in Berlin and Paris were a direct continuation of Gumilev's Poets' Workshop. This is how they were perceived by their contemporaries. If the literary ideology of the first, and, to some extent, the second and third "Workshop of Poets", was acmeism, then in the early 1920s it gradually transformed into "neoclassicism". Gumilev began to talk about this, and in criticism, both Soviet and emigre, they wrote about “neoclassicism” more than once: Zhirmunsky V. On Classical and Romantic Poetry The life of art. Feb. 10, 1920; Otsup N. About N. Gumilyov and classical poetry. Workshop of poets. 1922; Mochulsky K. Classicism in modern Russian poetry. Contemporary notes. 1922. No. 11, etc. True, almost every author put his own content into this term. It was more of a polemical self-definition, a reaction to Futurist and Imagist experiments with verse, than a truly thoughtful poetics. It had little in common with historical classicism.

Poet's Workshop in Berlin

In the winter of 1922-23, the "Poets' Workshop" tried to resume its activities in Berlin., where collections of poems by Ivanov and Otsup, three Petrograd almanacs "Workshops of Poets" were republished and the fourth, Berlin, was released. September 15, 1922 Otsup read his poems at the Berlin House of Arts at the opening of the winter season. October 13, 1922 at the annual general meeting in the Berlin House of Arts, G. Ivanov and Otsup spoke about the “Poets' Workshop” and read their poems at the evening of poets in the Berlin Writers' Club. In February 1923, Adamovich arrived, and on February 28, 1923, the evening "Poets' Workshop" was held in the cafe on Nollendorfplatz. in full force, about which a newspaper report appeared: "Georgy Adamovich's report on modern Russian poetry explains the literary position of the Workshop" (On the eve. 1923. March 10). Adamovich spent only a few days in Berlin. Ivanov, Odoevtseva and Otsup also soon left Berlin, and the next season of the Poets' Workshop was opened in 1923 in Paris.

Poet's Workshop in Paris

On November 1, 1923, the first evening of the "Workshop of Poets" took place in Paris, about which a report appeared in the “Link”, written, apparently, by Mochulsky: “The St. times ”(Shop of poets Link. 1923 November 26). The next meeting of the Guild of Poets was held on December 7 at Cafe La Bolee, and since then the famous cafe, once frequented by Villon, Wild and Verlaine, has become the permanent headquarters of the Parisian Guild of Poets for the next three seasons. Y.Terapiano described the atmosphere of the meetings in his memoir book: “Reading began “in a circle”, in a row, as they sat; to refuse, except in respectful cases - for example, if the next seated person turned out to be an artist and did not write poetry, it was considered unacceptable. Representatives of all literary trends and groups - from the most "left" to the most "right" in the formal sense. After the next author finished reading, an exchange of opinions began - also in a circle. It was not supposed to be shy, to be offended - it would be useless ”(Terpiano Y. Meetings. New York, 1953).

Unlike Gumilyov's "Poets' Workshop", there was no strict discipline in Paris, the meetings could be attended by poets of any direction, and they were not required to swear allegiance to "neoclassical" principles. There was no membership as such, so that in the full sense only four organizers continued to be considered members of the Guild of Poets, all the rest remained young Parisian poets. And yet, the Workshop of Poets played its role in the formation of emigre literature. In any case, the turn from the first, "avant-garde" period of émigré poetry to the "Parisian school" in the broadest sense of the word, obviously took place not without the influence of controversy in the cafe La Bolee.

In Soviet Russia, the émigré activities of the Poets' Guild were regarded as counter-revolutionary propaganda. See the articles by Gaik Adonts (Petersburgsky), editor of the newspaper Life of Art: “In the Service of the Counter-Revolution” (Life of Art, 1923. November 20 Signed: Petersburg) and “Khodasevich, Adamovich, Ivanov and Co.” (Life of Art, 1925, 15 Dec. Signature G.A.)

During the 1925-26 season, meetings of the Poets' Workshop were held less frequently than before. According to Terapiano, “with the advent of the Union of Young Poets and Writers in 1925, which began to organize large public evenings with reports and poetry readings, Bolle gradually began to disintegrate” (Terapiano Y. Meetings). The second and probably the main reason was that By the mid-1920s, the members of the Poets’ Guild changed their views on poetry. It was at this time that Adamovich wrote more and more often that “apparently, the recent outbreak of a new “classicism” is destined to fade soon” (Link. 1926 January 24). The last newspaper announcement inviting to the meeting of the Poets' Workshop was dated March 9, 1926. And by 1927, new ideas about poetry found their expression in the term "Parisian note". Inspired by the example of Gumilev's "Poets' Workshop", young writers in Russia and emigration of the 1920s and 30s organized numerous, but most often short-lived circles with the same name all over the world from Revel to Constantinople. More or less famous were: two Tiflis "Workshops of poets" (1918-19), the first under the leadership of Gorodetsky, the second - founded by Yuri Degen; Constantinople "Shop of Poets" (1920), founded by B.Yu.Poplavsky and Vl.Dukelsky; The Parisian "Workshop of Poets" (1920), founded by M.A. Struve and S.A. Sokolov-Krechetov; Baku "Workshop of Poets" (1920), organized by Gorodetsky; Moscow "Workshop of Poets" (1924-27), chaired first by Gorodetsky, then by A. Lunacharsky; "Yurievsky Workshop of Poets" (Tartu, 1929-32); "Revel Workshop of Poets" (1933-35).

Emergence of the “Poets' Workshop” St. Petersburg 2008 – 2009 academic year Introduction The Poets' Workshop is the name of several poetic associations that existed at the beginning of the 20th century in St. Petersburg, Moscow, Tbilisi, Baku, Berlin and Paris. "Poets' workshop" in St. Petersburg In fact, in St. Petersburg (Petrograd) there were three associations with the same name in turn. The first "Workshop of Poets" was founded by Gumilyov and Gorodetsky in 1911 and lasted until 1914. The first meeting of the association took place on October 20, 1911 in Gorodetsky's apartment.

In addition to the founders, Akhmatova (she was a secretary), Mandelstam, Zenkevich, Narbut, Kuzmina-Karavaeva, Lozinsky, Vasily Gippius, Moravskaya, and also at first Kuzmin, Piast, Alexei Tolstoy and others were in the "Workshop". The name of the association, consonant with the name of craft associations in medieval Europe, emphasized the attitude of the participants to poetry as a profession, a craft that required hard work. At first, the participants in the "Workshop" did not identify themselves with any of the trends in literature and did not strive for a common aesthetic platform, but in 1912 they declared themselves acmeists.

The creation of the "Workshop", its very idea was met by some poets with great skepticism. So, Igor Severyanin in the poem "Leander's Piano" wrote about its participants (while using a successful neologism that entered the Russian language, albeit with a different emphasis): Already there is a "shop of poets" (Where mediocrity, if not in the "shop") ! In one of the first printed responses to the emergence of the association, it was ironically stated: “Some of our young poets suddenly threw off their Greek togas and looked towards the craft council, forming their own workshop - the workshop of poets.” The association published poetry collections of the participants; poems and articles by members of the "Tsekh" were published in the journals "Hyperborea" and "Apollo". The association broke up in April 1914. The second "Workshop of Poets" operated in 1916 and 1917 under the leadership of Ivanov and Adamovich and was no longer focused on acmeism.

The third "Workshop of Poets" began to operate in 1920 under the leadership of first Gumilyov, and then Adamovich, and lasted two years. During its existence, the association has released four almanacs. "Workshop of Poets" in Moscow The association existed in 1924-1925.

The meetings took place at Antonovskaya's apartment. In 1925, the "Workshop" released the collection "Joint". "Workshop of Poets" in Tbilisi The association was founded on April 11, 1918 by Sergei Gorodetsky and lasted for about four years. At first, the participants were poets of different directions, but then the association declared itself acmeistic, and some of the participants left it.

According to the memoirs of Hripsime Poghosyan, a member of the association, about thirty poets were in the "Workshop". In 1918, the association published the almanac "AKME". The Poets' Guild in Baku The association existed for less than a year, in 1920, and was founded by Gorodetsky, who had moved to Baku from Tbilisi. "Poets' Workshop" in Europe After the emigration of some of the participants of the third "Poets' Workshop", associations with the same name were created by them in Berlin and Paris.

In 1923, the Berlin Poet's Workshop published a collection of poems with the same title. "Poets' Workshop", the name of three poetic associations that existed in St. Petersburg in 1911-22. In "C. P." a current of acmeism was formed. 1st "C. P." founded by N. S. Gumilyov and S. M. Gorodetsky in the autumn of 1911 as a society of novice writers who emerged from the so-called Academy of Verse, inspired by Vyach. I. Ivanov. "C. P." was the organization of the trade union of writers, focused on the discussion of the methods of literary skill and the analysis of the poetic text. "C. P." published the journal "Hyperborea" (1912-13), later almanacs.

The meetings were held at the apartments of Gorodetsky (143 Fontanka River Embankment), Gumilyov and A. A. Akhmatova in Tsarskoe Selo (53 Malaya Street), M. L. Lozinsky (1 Rumyantsevskaya Square), N. A. Bruni (apartment in the building of the Academy of Arts). In addition to the above, in this "C. P." included V. I. Narbut, M. A. Zenkevich, V. V. Gippius, G. V. Ivanov, O. E. Mandelstam, M. L. Moravskaya, Graal-Arelsky (S. S. Petrov), E. Yu. Kuzmina-Karavaeva and others. In the autumn of 1912, from the “Ts. P." a circle of acmeists stood out (Gorodetsky, Gumilyov, Akhmatova, Mandelstam, Narbut, Zenkevich). In April 1914, the unity of the circle was undermined by the conflict between Gorodetsky and Gumilyov, and after several meetings in the autumn of 1914 it ceased to exist.

At the initiative of two participants of the 1st “Ts. P." Ivanov and G.V. Adamovich from September 1916 to March 1917, on average, once a month, the 2nd “Ts. p.", which, unlike the 1st, had a minimal impact on literary life Petersburg.

In 1920 Gumilyov organized 3rd "C. the most active participants of which (Ivanov, Adamovich, N. A. Otsup, I. V. Odoevtseva), having left the USSR in 1922, for some time still supported the activities of this “Ts. P." in Berlin and Paris. The last “Ts. P." published 4 almanacs: 1st - "Dragon", reprinted in 1923 in Berlin under the title "Workshop of Poets". 1. The history of the emergence of the "Workshop of poets" Acmeism (from the Greek. acme – “the highest degree of something, flourishing, pinnacle, point”) is a current of Russian modernism that was formed in the 1910s and in its poetic attitudes is based on its teacher, Russian symbolism.

The transcendental two-worldliness of the symbolists was opposed by the acmeists to the world of ordinary human feelings, devoid of mystical content. By definition, V.M. Zhirmunsky, acmeists - "overcoming symbolism". The name that the acmeists chose for themselves was supposed to indicate the desire for the heights of poetic skill.

Acmeism as a literary trend arose in the early 1910s and was genetically associated with symbolism. In the 1900s, young poets who were close to symbolism at the beginning of their career attended "Ivanovo environments" - meetings at the St. Petersburg apartment of Vyach. Ivanov, which received the name "tower" among them. In the depths of the circle in 1906-1907, a group of poets gradually formed, calling itself the "circle of the young." The impetus for their rapprochement was opposition (still timid) to symbolist poetic practice.

On the one hand, the “young” sought to learn poetic technique from their older colleagues, but on the other hand, they would like to overcome the speculation and utopianism of symbolist theories. It is necessary to note the ancestral connection of acmeism with the literary group “Poets' Workshop”. The Workshop of Poets was founded in October 1911 in St. Petersburg in opposition to the Symbolists, and the protest of the members of the group was directed against the magical, metaphysical nature of the language of Symbolist poetry.

The group was headed by N. Gumilev and S. Gorodetsky. The group also included A. Akhmatova, G. Adamovich, K. Vaginov, M. Zenkevich, G. Ivanov, V. Lozinsky, O. Mandelstam, V. Narbut, I. Odoevtseva , O. Otsup, V. Rozhdestvensky. "Tsekh" published the journal "Hyperborey". The name of the circle, formed on the model of the medieval names of craft associations, indicated the attitude of the participants to poetry as a purely professional field of activity. The "workshop" was a school of formal craftsmanship, indifferent to the peculiarities of the worldview of the participants.

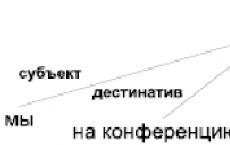

At first, they did not identify themselves with any of the currents in literature, and did not strive for a common aesthetic platform. From a wide circle of participants in the "Workshop" in the early 1910s (circa 1911-1912), a narrower and more aesthetically more cohesive group of poets stood out, who began to call themselves acmeists. The group included N. Gumilyov, A. Akhmatova, O. Mandelstam , S. Gorodetsky, M. Zenkevich, V. Narbut (other members of the "Workshop", among them G. Adamovich, G. Ivanov, M. Lozinsky, constituted the periphery of the current). 2. Literary manifestos of the acmeists It is characteristic that the most authoritative teachers for the acmeists were poets who played a significant role in the history of symbolism - M. Kuzmin, I. Annensky, A. Blok. The literary manifestos of the acmeists were preceded by an article by M. Kuzmin “On beautiful clarity”, which appeared in 1910 in the journal Apollo. The article declared the stylistic principles of “beautiful clarity”: the logicality of the artistic conception, the harmony of the composition, the clarity of the organization of all elements of the artistic form: “Love the word, like Flaubert, be economical in means and stingy in words, accurate and genuine, and you will find the secret of a wonderful thing - beautiful clarity - which I would call "clarism"". In January 1913, manifestoes of acmeist poets appeared: an article by N. Gumilyov “The Heritage of Symbolism and Acmeism” and an article by S. Gorodetsky “Some Trends in Modern Russian Poetry” (magazine “Apollo”). N. Gumilyov's article "The Heritage of Symbolism and Acmeism" (1913) opens with the following words: "It is clear to the attentive reader that symbolism has completed its circle of development and is now falling." N. Gumilyov called symbolism a “worthy father”, but at the same time emphasized that the new generation had developed a different, “courageously firm and clear outlook on life”. Acmeism, according to Gumilyov, is an attempt to rediscover the value of human life, the real world. Surrounding a person reality for the acmeist is valuable in itself and does not need metaphysical justifications.

Therefore, one should stop flirting with the transcendent (going beyond human knowledge) and return to the image of the three-dimensional world; the simple objective world must be rehabilitated; it is significant in itself, and not only in that it reveals higher beings.

N. Gumilyov renounces the "unchaste" desire of the Symbolists to cognize the unknowable: "the unknowable by the very meaning of this word cannot be known. All attempts in this direction are unchaste." The main thing in the poetry of acmeism is the artistic development of the diverse and vibrant real earthly world. S. Gorodetsky spoke even more categorically in this sense in the article “Some Trends in Modern Russian Poetry” (1913): “The struggle between acmeism and symbolism is primarily a struggle for this world, sounding, colorful, having forms, weight and time Symbolism, in in the end, having filled the world with “correspondences”, he turned it into a phantom, important only insofar as he sees through and shines through other worlds, and belittled his high intrinsic value.

Among the Acmeists, the rose again became good in itself, with its petals, smell and color, and not with its conceivable similarities with mystical love or anything else. After all sorts of "rejections, the world is irrevocably accepted by acmeism, in the totality of beauties and ugliness." This statement by S. Gorodetsky echoes the famous poem by A. Akhmatova “I don’t need odic rati” (1940) from the cycle “Secrets of the Craft”: I don’t need odic rati And the charm of elegiac undertakings.

For me, in poetry, everything should be out of place, Not like people do.

If only you knew from what rubbish Poems grow without shame, Like a yellow dandelion near a fence, Like burdocks and quinoa.

An angry cry, a fresh smell of tar, A mysterious mold on the wall And the verse already sounds, fervent, gentle, For the joy of you and me. Acmeist, like Adam - the first person - had to rediscover life, the real, earthly world and give everything their own names.

S. Gorodetsky wrote: “But this new Adam did not come to the untouched and virgin world on the sixth day of creation, but to Russian modernity.

He looked around here with the same clear, keen eye, accepted everything he saw, and sang alleluia to life and the world. See, for example, S. Gorodetsky's poem "Adam": The world is spacious and polyphonic, And it is more colorful than rainbows, And now it is entrusted to Adam, the Inventor of names. Name, recognize, rip off the covers.

And idle secrets, and dilapidated darkness - This is the first feat. A new feat - to sing praises to the Living Earth. The acmeist poets, for all the catchiness of their statements, did not put forward a detailed philosophical and aesthetic program. The new trend brought with it not so much a novelty of worldview as a novelty of poetic language, taste sensations. In contrast to symbolism, imbued with the “spirit of music”, acmeism was focused on spatial arts: painting, architecture, sculpture.

Unlike futurism, which also arose as a movement directed against symbolism, acmeism did not proclaim a revolutionary change in poetic technique, but strove for the harmonious use of everyday language in the field of poetry. In the poetry of acmeism, the picturesque clarity of images, precisely measured composition, and sharpness of details were valued. The world of the acmeist poet is an objective world in which an important place was given to artistic detail.

A colorful, sometimes even exotic detail could be used non-utilitarian, in a purely pictorial function. Acmeism, denying much in the aesthetics of symbolism, creatively used its achievements: “The concreteness, the “materialistic” vision of the world, scattered and lost in the mists of symbolic poetry, was again returned to the Russian poetic culture of the twentieth century precisely through the efforts of Mandelstam, Akhmatova, Gumilyov and their other poets ( acmeist) circle. But the specificity of their imagery was already different than in the poetry of the past, XIX century. Lyrics of Mandelstam, like those of his fellow poets, survived and incorporated the experience of the Symbolists, especially Blok, with their sharpest sense of infinity and cosmic being. 3. Gumilyov and the "Workshop of Poets" The movement started by the Symbolists meant the expansion of the poetic horizon, the liberation of individuality, and the raising of the level of technology; in this sense, it is on the rise, and all Russian poetry worthy of attention from the beginning of the century to the present day belongs to the same school.

But the differentia specifica of the Symbolist poets - their metaphysical aspirations, their conception of the world as a system of similitudes, their tendency to equate poetry with music - were not taken up by their heirs.

The generation of poets born after 1885 continued the revolutionary and cultural work of the symbolists - but ceased to be symbolists. Around 1910, the symbolist school began to disintegrate, and in the next few years new, rival schools arose, the most important of which were the acmeists and futurists.

Acmeism (this ridiculous word was first uttered ironically by an adversary symbolist, and the new school defiantly adopted it as a name; however, this name was never particularly popular and hardly still exists) was based in St. Petersburg. Its founders were Gorodetsky and Gumilyov, and this was a reaction to the position of the Symbolists. They refused to see things only as signs of other things.

They wanted to admire the rose, they said, because it was beautiful, not because it was a symbol of mystical purity. They wanted to see the world with a fresh and unprejudiced eye, "as Adam saw it at the dawn of creation." Their teaching was a new realism, but a realism open to the concrete essence of things. They sought to avoid the wolf pits of aestheticism and declared their masters (strange selection) Villon, Rabelais, Shakespeare and Theophile Gautier. From the poet they demanded liveliness of gaze, emotional strength and verbal freshness.

But, in addition, they wanted to make poetry a craft, and the poet - not a priest, but a master. The creation of the Guild of Poets was an expression of this trend. The Symbolists, who wanted to turn poetry into a religious service (“theurgy”), greeted the new school with disapproval and to the end (especially Blok) remained staunch opponents of Gumilyov and Tsekh. I spoke about one of the founders of the Guild of Poets, Gorodetsky, earlier. By 1912, he had already outlived his talent. We can no longer mention him in this connection (we only note that Gorodetsky, who wrote extremely chauvinistic military poems in 1914, became a communist in 1918 and immediately after Gumilyov was executed Bolsheviks, wrote about him in the tone of the most servile reproach). Nikolai Stepanovich Gumilyov, not to mention his historical significance, is a true poet. Born in 1886 in Tsarskoe Selo, studied in Paris and St. Petersburg.

In 1910 Gumilev married Anna Akhmatova. The marriage proved unstable and they divorced during the war. In 1911 he traveled through Abyssinia and British East Africa, where he went again shortly before the war of 1914. He retained a particular fondness for Equatorial Africa. In 1912, as we have already said, he founded the Workshop of Poets. At first, the poems of the members of the Workshop did not have much success with the public. In 1914, Gumilyov, the only Russian writer, went to the front as a soldier (in the cavalry). He took part in the August 1914 campaign in East Prussia, was twice awarded the George Cross; in 1915 he was promoted to officer. In 1917 he was seconded to Russian units in Macedonia, but the Bolshevik revolution found him in Paris.

In 1918 he returned to Russia, in no small measure out of adventurism and a love of danger. "I hunted lions," he said, "and I don't think the Bolsheviks are much more dangerous." For three years he lived in St. Petersburg and its environs, took part in Gorky's vast translation enterprises, taught the art of versification to young poets, and wrote his best poems. In 1921, he was arrested on charges (apparently false) of conspiracy against the Soviet government and, after several months in prison, was shot on August 23, 1921, by order of Chek. He was then in the prime of his talent; His last book is better than all the previous ones, and the most promising.

Gumilyov's poems are collected in several books, the main of which are: Zhemchuga (1910), Alien Sky (1912), Quiver (1915), Bonfire (1918), Tent (1921) and Pillar of Fire (1921); Gondla, a play in verse from Icelandic history, and Mik, an Abyssinian tale.

He has few stories in prose and they do not matter - they belong to the early period and were written under the very noticeable influence of Bryusov. Gumilyov's poems are completely different from ordinary Russian poetry: they are bright, exotic, fantastic, always in a major key and dominated by a rare Russian literature note - the love of adventure and courageous romanticism.

An early book of his, Pearls, full of exotic gems, sometimes not in the best taste, includes Captains, a poem written in praise of great sailors and adventurers of the high seas; with characteristic romanticism, it ends with the image of the Flying Dutchman. His military poetry is completely free, oddly enough, from "political" feelings - he is least of all interested in the goals of the war. There is a new religious note in these war verses, unlike the mysticism of the Symbolists - it is a boyish, unreasoning faith, full of joyful sacrifice.

The tent, painted in Bolshevik Petersburg, is something like a poetic geography of his beloved continent of Africa. The most impressive part of it is the Equatorial Forest - the story of a French explorer in the malaria forest Central Africa, among gorillas and cannibals. Best Books Gumilyov - The Bonfire and the Pillar of Fire. Here his verse acquires emotional intensity and seriousness, which are absent in his early works.

Here is printed such an interesting manifesto as My Readers, where he proudly says that he feeds his readers not with humiliating and relaxing food, but with that which will help them face death like a man calmly. In another poem, he expresses the desire to die a violent death, and "not on the bed, with a notary and a doctor." This desire was fulfilled. His poetry sometimes becomes nervous, like a strange ghostly Lost tram, but more often it reaches courageous grandeur and seriousness, as in his wonderful dialogue with his soul and body, where the monologue of the body ends with noble words: But I am for everything that I took and I want, For all the sorrows, joys and nonsense, As befits a husband, I will pay Irreparable death of the latter. The last poem of this book is Star Horror, a mysterious and strangely compelling account of how primitive man first dared to look at the stars.

Before his death, Gumilyov worked on another poem about primitive times - the Dragon.

It is a strangely original and fantastic cosmogony, only the first canto of which has been completed. The remaining poets of the Workshop are mostly imitators of Gumilyov or their common predecessor, Kuzmin. Although they write pleasantly and skillfully, it is not worth dwelling on them; their work is “school work”. They will be remembered rather as the main characters of the cheerful and frivolous “vie de Bohème”, the life of the St. Petersburg bohemia of 1913-1916, the center of which was the artistic cabaret “Stray Dog”. But the two poets associated with the Workshop - Anna Akhmatova and Osip Mandelstam - are more significant figures.

What will we do with the received material:

If this material turned out to be useful to you, you can save it to your page on social networks:

Composition

Starting from symbolism, Gumilyov defined the poetics of the new trend extremely vaguely. The era of Russian life was tragically experienced by Blok. At one time, A. Blok called the “Workshop of Poets” the “Gumilyov-Gorodets Society”. Indeed, Gumilyov and Gorodetsky were theorists and founders of acmeism. Probably the most prominent representative of the school of acmeism is Anna Akhmatova (A. A. Gorenko, 1889-1966). “Only Akhmatova went as a poet along the paths of the new artistic realism she discovered, closely connected with the traditions of Russian classical poetry ...” Blok called her “a real exception” among acmeists. But at the same time, the early work of Anna Akhmatova expressed many principles of acmeistic aesthetics, perceived by the poetess in an individual sense.

The nature of Akhmatova's worldview already delimited her, an acmeist, from acmeism. Contrary to the acmeistic call to accept reality "in the totality of beauties and ugliness", Akhmatova's lyrics are filled with the deepest drama, a keen sense of fragility, disharmony of being, an approaching catastrophe. That is why so often in her poems there are motives of misfortune, grief, longing, near death ("The heart languished, not even knowing the Cause of its grief", etc.). The "voice of trouble" constantly sounded in her work. Akhmatova’s lyrics stood out from the socially indifferent poetry of acmeism and the fact that in the early poems of the poetess the main theme of all her subsequent work was already more or less clearly identified - the theme of the Motherland, a special, intimate feeling of high patriotism (“You know, I am languishing in captivity ... ”, 1913; “I will come there, and languor will fly away ...”, 1916; “Prayer”, 1915, etc.).

Akhmatova created vivid, emotional poetry; more than any of the acmeists, he bridged the gap between poetic and colloquial speech. She eschews metaphorization, the complexity of the epithet, everything in her is built on the transfer of experience, the state of the soul, on the search for the most accurate visual image. early poetry Akhmatova has already predicted her wonderful gift of discovering man. So far, her hero does not have broad horizons, but he is serious, sincere and in small things. And most importantly, the poetess loves a person, believes in his spiritual strength and abilities. That is why her poems are perceived as such a penetrating page, not only in comparison with acmeist performances, but also against the background of Russian poetry in general at the beginning of the 20th century. Associated with the acmeist movement creative way O. E. Mandelstam (1891-1938). At the first stages of his creative development, Mandelstam experiences a certain influence of symbolism.

The pathos of his poems of the early period is the renunciation of life with its conflicts, the poeticization of chamber solitude, joyless and painful, the feeling of the illusory nature of what is happening, the desire to escape into the sphere of the original ideas about the world (“Only children's books to read”, “Silentium” and others). Mandelstam's approach to acmeism is due to the poet's demand for "beautiful clarity" and "eternity" of images. In the works of the 1910s, collected in the book "Stone" (1913), the poet creates the image of a "stone", from which he "builds" buildings, "architecture", the form of his poems. For Mandelstam, the images of poetic art are "an architecturally justified ascent, corresponding to the tiers of a Gothic cathedral." The work of Mandelstam expressed the desire to escape from tragic storms, time into the timeless, into the civilizations and cultures of past centuries.

The poet creates a kind of secondary world from the cultural history he perceives, a world built on subjective associations through which he tries to express his attitude to modernity, arbitrarily grouping the facts of history, ideas, literary images (“Dombey and Son”, “Europe”, “I did not hear the stories of Ossian…”). It was a peculiar form of leaving one's "age - the ruler". From the poems of "Stone" breathes loneliness, melancholy, world misty pain.

In acmeism, Mandelstam occupied a special position. No wonder A. Blok, speaking later about the acmeists and their epigones, singled out Akhmatova and Mandelstam from this environment as masters of truly dramatic lyrics. Defending in 1910 - 1916. aesthetic "decisions" of his "Workshop", the poet already then largely disagreed with Gumilyov and Gorodetsky. Mandelstam was alien to the Nietzschean aristocracy of Gumilyov, the programmatic rationalism of his romantic works, subordinated to a predetermined pathos of pathos. The path of Mandelstam's creative development was also different compared to Gumilyov. The dramatic intensity of Mandelstam's lyrics expressed the poet's desire to overcome pessimistic moods, the state of internal struggle with himself. In his later poems, the tragic theme of loneliness, and love of life, and the desire to become an accomplice to the "noise of time" ("No, never, I was nobody's contemporary", "Stans", "Lost in the sky") sound. In the field of poetics, he went from the imaginary "materiality" of the "stone", as V. M. Zhirmunsky wrote, "to the poetics of complex and abstract allegories, consonant with such a phenomenon of late symbolism in the West as the poetry of Paul Valery and the French surrealists ...".

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, an interesting phenomenon appeared in Russian literature, later called "poetry". silver age". The "golden age" of Russian poetry, associated with the appearance in the sky of such "stars of the first magnitude" as Pushkin and Lermontov, was undoubtedly due to the general trend towards the development of Russian national literature, Russian literary language and development of realism. A new surge of the poetic spirit of Russia is associated with the desire of contemporaries to renew the country, renew literature, and with a variety of modernist trends, as a result, that appeared at that time.

They were very diverse both in form and in content: from a solid, numbering several generations and several decades of symbolism to the still emerging Imagism, from acmeism promoting “a courageously firm and clear outlook on life” (N. Gumilyov) to shocking the public , cheeky, sometimes just hooligan futurism.

Thanks to such different directions and currents, new names appeared in Russian poetry, many of which happened to stay in it forever. The great poets of that era, starting in the bowels of the modernist movement, very quickly grew out of it, striking with their talent and versatility of creativity. This happened with Blok, Yesenin, Mayakovsky, Gumilyov, Akhmatova, Tsvetaeva, Voloshin and many others. Conventionally, the beginning of the "Silver Age" is considered to be 1892, when the ideologist and oldest member of the Symbolist movement Dmitry Merezhkovsky read a report "On the Causes of the Decline and New Trends in Modern Russian Literature." So for the first time the symbolists, and hence the modernists, declared themselves.

) there were in turn three associations with the same name.

The first "Workshop of poets" was founded by Gumilyov and Gorodetsky in the year and lasted up to a year. The first meeting of the association took place on October 20, 1911 in Gorodetsky's apartment. Only those invited were present, which gave the association an aura of mystery.

In addition to the founders, Akhmatova (she was a secretary), Mandelstam, Zenkevich, Narbut, Kuzmina-Karavaeva, Lozinsky, Vasily Gippius, Maria Moravskaya, Vera Gedroits, as well as at first Kuzmin, Piast, Alexei Tolstoy, and others.

The name of the association, following the model of craft associations in medieval Europe, emphasized the attitude of the participants to poetry as a profession, a craft that required hard work. At the head of the workshop was a syndic, chief master. According to the plan of the organizers, their workshop was supposed to serve for the knowledge and improvement of the poetic craft. Apprentices had to learn to be poets. Gumilyov and Gorodetsky believed that a poem, i.e. "Thing" is created according to certain laws, "technologies". These techniques can be learned. Officially, there were three syndics: Gumilyov, Gorodetsky, Dm. Kuzmin-Karavaev (lawyer, loved poetry and helped these people publish poetry, etc.).

At first, the participants in the "Workshop" did not identify themselves with any of the currents in literature and did not strive for a common aesthetic platform, but in the year they declared themselves acmeists.

The creation of the "Workshop", its very idea was met by some poets with great skepticism. So, Igor Severyanin in the poem "Leander's Piano" wrote about its participants (while using a successful neologism that entered the Russian language, albeit with a different emphasis):

Already there is a "Workshop of poets"

(Where mediocrity, if not in the "workshop")!

One of the first printed responses to the emergence of the association ironically stated: "Some of our young poets unexpectedly threw off their Greek togas and looked towards the craft council, forming their own workshop - the workshop of poets."

The association published poetry collections of the participants; poems and articles by members of the "Workshop" were published in the journals Hyperborea and Apollo. The association disbanded in April.

The second "Workshop of poets" acted in and years under the leadership of Ivanov and Adamovich and was no longer concentrated on acmeism.

The third "Workshop of poets" began to operate in the year under the leadership of first Gumilyov, and then Adamovich and lasted two years. During its existence, the association has produced three almanacs; the first under the title "Dragon" (According to the first song published in it poem of the same name N.S. Gumilyov; not completed).

1.1. Workshop of poets

In the autumn of 1921 in the poetic salon of Vyacheslav Ivanov " Prodigal son» N. Gumilyov suffered a real defeat. The speech of the symbolists condemning him was so rude and harsh that the poet and his friends left " tower"and organized a new commonwealth -" Workshop of poets».

The name of the association, consonant with the name of craft associations in medieval Europe, emphasized the attitude of the participants to poetry as a profession, a craft that required hard work.

At the meetings Workshops”, in contrast to the meetings of the symbolists, specific issues were resolved: “ Shop”was a school for mastering poetic skills. The workshop was supposed to serve for the knowledge and improvement of the poetic craft. Apprentices had to learn to be poets.

Gumilyov And Gorodetsky believed that the poem, i.e. " thing", is created according to certain laws," technologies". These techniques can be learned.

At the meetings Workshops» Poems were analyzed, problems of poetic skill were solved, methods of analysis of works were substantiated. At first, the participants Workshops” did not identify themselves with any of the currents in literature and did not strive for a common aesthetic platform.

At various times at work Workshops of poets"participated: G. Adamovich, N. Bruni, Vasily Vasilyevich Gippius, Vladimir Vasilyevich Gippius, G. Ivanov, N. Klyuev, M. Kuzmin, E. Kuzmina-Karavaeva, M. Lozinsky, S. Radlov, V. Khlebnikov.

1.2. Acmeism

Creation by N. Gumilyov and S. Gorodetsky " Workshops of poets"in 1911, as opposed to the abandoned by them" Academy of verse” led to the emergence of a new poetic trend.Since 1912, this trend has been called - Acmeism(from Greek. akme- the highest degree of something, flourishing, maturity, peak). The term was also used Adamism, which Gumilyov defined as " courageously firm and clear view of the world».

« Away with symbolism, long live the living rose!"- exclaimed O. Mandelstam.

Acmeism stood out from symbolism, criticizing its mystical aspirations to " unknowable»: « Among the Acmeists, the rose again became good in itself, with its petals, smell and color, and not with its conceivable similarities with mystical love or anything else."- said Gorodetsky.

Acmeists proclaimed the materiality, objectivity of subjects and images, the accuracy of the word. Acmeism is a cult of concreteness, materiality» image, this is « the art of precisely measured and measured words».

Acmeists tried with all their might to bring literature back to life, to things, to man, to nature. " As Adamists, we are a bit of forest animals, - Gumilyov declares, - and, in any case, we will not give up what is bestial in us in exchange for neurasthenia».

They began to fight, as they put it, " for this world, sounding, colorful, having shapes, weight and time, for our planet earth».

Acmeism preached " simple» poetic language, where the words would directly name the objects.

Compared with symbolism and related movements - surrealism And futurism- one can single out, first of all, such features as the materiality and this-worldliness of the depicted world, in which " each depicted object is equal to itself».

Acmeists from the very beginning declared their love for objectivity. Gumilyov urged to seek not " unsteady words", and the words" with more stable content". The materiality determined the predominance of nouns in poetry and the insignificant role of the verb.

- Affirmation of the rights of the concrete-sensual word in poetry;

- Returning the word to its original, simple meaning, freeing it from symbolic interpretations;

- The chanting of the earthly world in all its multicolor and power.