Did Gogol meet with Zagoskin m. Literary and everyday memories Gogol (Zhukovsky, Krylov, Lermontov, Zagoskin). Anniversary premieres: "Taras Bulba"

Gogol

(Zhukovsky, Krylov, Lermontov, Zagoskin)

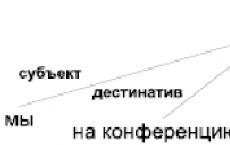

The late Mikhail Semyonovich Shchepkin brought me to Gogol. I remember the day of our visit: October 20, 1851. Gogol then lived in Moscow, on Nikitskaya, in the house of Talyzin, with Count Tolstoy. We arrived at one o'clock in the afternoon; he received us immediately. His room was near the entrance to the right. We entered it - and I saw Gogol standing in front of the desk with a pen in his hand. He was wearing a dark coat, a green velvet waistcoat, and brown trousers. A week before that day I had seen him at the theater, at a performance of The Government Inspector; he was sitting in the mezzanine box, near the door itself - and, with his head thrown out, looked with nervous anxiety at the stage, over the shoulders of two hefty ladies, who served him as a protection from the curiosity of the public. F, who was sitting next to me, pointed him out to me. I quickly turned around to look at him; he probably noticed this movement and moved a little back into the corner. I was struck by the change that had taken place in him since the age of 41. I met him a couple of times then at Avdotya Petrovna E-naya's. At that time he looked like a squat and stocky Little Russian; now he seemed to be a thin and exhausted man, whom life had already managed to beat up on orders. A kind of hidden pain and anxiety, a kind of sad unease, mingled with the constantly shrewd expression of his face.

Seeing us with Shchepkin, he went to meet us with a cheerful look and, shaking my hand, said: "We should have known each other for a long time." We sat down. I am next to him on a wide sofa; Mikhail Semyonitch on the armchairs beside him. I took a closer look at his features. His blond hair, which fell straight from the temples, as is usual with the Cossacks, still retained the color of youth, but had already noticeably thinned; from his sloping, smooth, white forehead, as before, it wafted with intelligence. In the small brown eyes sparkled at times with gaiety - precisely gaiety, and not mockery; but in general their eyes seemed tired. A long, pointed nose gave Gogol's physiognomy something cunning, fox-like; his puffy, soft lips under a cropped mustache also made an unfavorable impression; in their indefinite outlines were expressed - so, at least, it seemed to me - the dark sides of his character: when he spoke, they uncomfortably opened and showed a row of bad teeth; a small chin sank into a wide black velvet cravat. In Gogol's posture, in his body movements, there was something not professorial, but teacher's - something reminiscent of teachers in provincial institutes and gymnasiums. “What a smart, and strange, and sick creature you are!” - involuntarily thought, looking at him. I remember that Mikhail Semyonovich and I went to see him as to an extraordinary, brilliant person who had something in his head ... all of Moscow had such an opinion about him. Mikhail Semyonovich warned me that one should not talk to him about the continuation of Dead Souls, about this second part, on which he worked so long and so hard and which, as you know, he burned before his death; that he does not like this conversation. I myself would not mention Correspondence with Friends, since I could not say anything good about it. However, I did not prepare for any conversation - but simply longed to see a man whose creations I almost knew by heart. It is even difficult for today's young people to interpret the charm that surrounded his name then; now there is no one on whom general attention could be focused.

Shchepkin announced to me beforehand that Gogol was not talkative; in reality it turned out differently. Gogol talked a lot, with animation, measuredly pushing away and rapping out every word - which not only did not seem unnatural, but, on the contrary, gave his speech some pleasant gravity and impressionability. He spoke in 6, I did not notice any other less pleasant features of the Little Russian dialect for the Russian ear. Everything came out well, smoothly, tasty and well-aimed. The impression of weariness, morbid, nervous restlessness which he had at first made upon me has vanished. He talked about the meaning of literature, about the vocation of a writer, about how one should treat one's own works; made several subtle and correct remarks about the very process of work, about the very, if I may say so, the physiology of writing; and all this - in figurative, original language - and, as far as I could see, not at all prepared in advance, as is often the case with "celebrities". Only when he started talking about censorship, almost glorifying it, almost approving it as a means of developing skill in a writer, the ability to protect his offspring, patience and many other Christian and secular virtues, only then it seemed to me that he draws from a ready-made arsenal. Moreover, to prove in this way the necessity of censorship - did it not mean to recommend and almost praise the cunning and cunning of slavery? I can still admit the verse of the Italian poet: “Si, servi siam; ma servi ognor fre-menti ”(We are slaves ... yes; but slaves, eternally indignant); but the self-satisfied humility and knavery of slavery... no! better not to talk about it. In such fabrications and reasonings of Gogol, the influence of those persons of the highest flight, to whom most of the "Correspondence" is devoted, was too clearly shown; from there came this musty and insipid spirit. In general, I soon felt that between Gogol's world outlook and mine lay a whole abyss. Not the same thing we hated, not the same thing we loved; but at that moment - in my eyes, none of that mattered. A great poet, a great artist was in front of me, and I looked at him, listened to him with reverence, even when I did not agree with him.

Gogol probably knew my relationship with Belinsky, with Iskander; about the first of them, about his letter to him - he did not hint: this name would have burned his lips. But at that time, Iskander's article had just appeared - in a foreign publication - in which, regarding the notorious "Correspondence", he reproached Gogol for apostasy from his former convictions. Gogol himself spoke about this article. From his letters printed after his death (oh, what a service the publisher would have rendered him if he had thrown out of them the whole two-thirds, or at least all those written to society ladies ... a more disgusting mixture of pride and search, hypocrisy and vanity, a prophetic and hanger-on tone - does not exist in literature!) - from Gogol's letters we know what an incurable wound in his heart was the complete fiasco of his "Correspondence" - this is a fiasco in which one of the few consoling manifestations of the then public opinion must be welcomed . And the late MS Shchepkin and I were witnesses - on the day of our visit - to what extent this wound became sore. Gogol began to assure us - in a suddenly changed, hurried voice - that he could not understand why in his previous writings some people find some kind of opposition, something that he later changed; that he always adhered to the same religious and protective principles - and, as proof of this, he is ready to point out to us some places in one of his books, already published a long time ago ... Having uttered these words, Gogol jumped up from the sofa with almost youthful vivacity and ran to adjacent room. Mikhail Semenych only raised his eyebrows in grief - and raised his index finger ... "I never saw him like that," he whispered to me.

Gogol returned with a volume of "Arabesques" in his hands and began to read for excerpt some passages from one of those childishly pompous and tiresomely empty articles with which this collection is filled. I remember that it was about the need for strict order, unconditional obedience to the authorities, etc. “You see,” Gogol repeated, “I always thought the same thing before, expressed exactly the same convictions as now! .. Why on earth? reproach me for treason, for apostasy… Me?” - And this was said by the author of The Inspector General, one of the most negative comedies that ever appeared on the stage! Shchepkin and I were silent. Gogol finally threw the book on the table and spoke again about art, about the theatre; announced that he was dissatisfied with the performance of the actors in The Inspector General, that they "lost their tone" and that he was ready to read the whole play to them from beginning to end. Shchepkin seized on this word and immediately arranged where and when to read. Some old lady came to Gogol; she brought him a prosphora with a particle taken out. We left.

Two days later, the reading of The Inspector General took place in one of the halls of the house where Gogol lived. I requested permission to attend this reading. The late Professor Shevyrev was also among the students and, if I am not mistaken, Pogodin. To my great surprise, not all the actors who participated in The Government Inspector came to Gogol's invitation; it seemed insulting to them that they seemed to want to teach them! Not a single actress came either. As far as I could see, Gogol was upset by this reluctant and weak response to his proposal ... It is known to what extent he skimped on such favors. His face assumed a sullen and cold expression; eyes were suspicious. That day he looked like a sick man. He began to read - and gradually perked up. Her cheeks were covered with a light color, her eyes widened and brightened. Gogol read excellently ... I listened to him then for the first - and for the last time. Dickens, also an excellent reader, can be said to act out his novels, his reading is dramatic, almost theatrical; in one of his faces there are several first-class actors who make you laugh or cry; Gogol, on the contrary, struck me with the extreme simplicity and restraint of his manner, with a kind of important and at the same time naive sincerity, which, as it were, does not care whether there are listeners here and what they think. It seemed that Gogol's only concern was how to delve into a subject that was new to him and how to more accurately convey his own impression. The effect was extraordinary - especially in comic, humorous places; it was impossible not to laugh - a good, healthy laugh; and the originator of all this fun continued, not embarrassed by the general gaiety and as if inwardly marveling at it, more and more immersed in the matter itself - and only occasionally, on the lips and near the eyes, the craftsman's sly smile trembled almost noticeably. With what bewilderment, with what amazement, Gogol uttered Gorodnichiy's famous phrase about two rats (at the very beginning of the play): "Come, sniff and go away!" - He even looked at us slowly, as if asking for an explanation for such an amazing occurrence. It was only then that I realized how completely wrong, superficially, with what desire to make you laugh as soon as possible, The Inspector General is usually played on the stage. I sat immersed in joyful emotion: it was for me a real feast and holiday. Unfortunately, it didn't last long. Gogol had not yet had time to read half of the first act, when suddenly the door was noisily opened and, hastily smiling and nodding his head, rushed across the whole room one still very young, but already unusually importunate writer - and, without saying a word to anyone, hurried to take a place in the corner . Gogol stopped; He struck the bell with his hand with a flourish and remarked heartily to the valet who entered: “After all, I ordered you not to let anyone in!” The young man of letters moved slightly in his chair, but he was not in the least embarrassed. Gogol drank some water - and again began to read; but that wasn't it at all. He began to hurry, muttering under his breath, not finishing his words; sometimes he skipped entire sentences and only waved his hand. The unexpected appearance of the writer upset him: his nerves, obviously, could not withstand the slightest shock. Only in the well-known scene where Khlestakov lies lies, Gogol again cheered up and raised his voice: he wanted to show the actor who played the role of Ivan Alexandrovich how this really difficult place should be conveyed. In reading Gogol, it seemed natural and plausible to me. Khlestakov is fascinated by the strangeness of his position, his environment, and his own frivolous briskness; he knows that he is lying - and he believes his lies: this is something like ecstasy, inspiration, creative delight - this is not a simple lie, not a simple boast. He himself was "caught up". “The petitioners in the hall are buzzing, 35 thousand relay races are jumping - and the foolish one, they say, is listening, hanging his ears, and what a lively, playful, secular young man I am!” This is the impression that Khlestakov's monologue made in Gogol's mouth. But, generally speaking, reading The Inspector General that day was - as Gogol himself put it - nothing more than a hint, a sketch; and all at the mercy of the uninvited writer, who extended his unceremoniousness to the point that he stayed after everyone else at the pale, tired Gogol and rubbed himself into his office after him. In the hallway I parted from him and never saw him again; but his personality was still destined to have a significant influence on my life.

In the last days of February of the following month, 1852, I was at one morning meeting of the Society for Visiting the Poor that soon died - in the hall of the Nobility Assembly - and suddenly I noticed I. I. Panaev, who with convulsive haste ran from one person to another, obviously informing everyone of them unexpected and sad news, for each face immediately expressed surprise and sadness. Panaev finally ran up to me - and with a slight smile, in an indifferent tone, he said: “Do you know, Gogol died in Moscow. How, how ... I burned all the papers - and died, ”I rushed further. There is no doubt that, as a writer, Panaev inwardly mourned over such a loss - moreover, he had a good heart - but the pleasure of being the first person to tell another upsetting news (an indifferent tone was used for greater force) - this is a pleasure, this joy was drowned out in him any other feeling. For several days dark rumors had been circulating in Petersburg about Gogol's illness; but no one expected such an outcome. Under the first impression of the news communicated to me, I wrote the following short article:

Letter from Petersburg

Gogol is dead! What Russian soul will not be shaken by these two words? He died. Our loss is so cruel, so sudden, that we still do not want to believe it. At the very time when we could all hope that he would finally break his long silence, that he would please, surpass our impatient expectations, this fateful news came! Yes, he died, this man whom we now have the right, the bitter right given to us by death, to call great; a man who, with his name, marked an era in the history of our literature; a person whom we are proud of as one of our glory. He died, stricken in the prime of his life, in the midst of his strength, without finishing the work he had begun, like the noblest of his predecessors ... His loss renews grief for those unforgettable losses, just as a new wound excites the pain of ancient ulcers. Now is not the time or place to talk about his merits - this is a matter for future criticism; one must hope that she will understand her task and appreciate him with that impartial, but full of respect and love court, by which people like him are judged in the face of posterity; we are not up to it now: we only want to be one of the echoes of that great sorrow that we feel spilled all around us; we do not want to appreciate it, but to cry; we are now unable to speak calmly about Gogol ... the most beloved, most familiar image is unclear to eyes watered with tears ... On the day when Moscow buries him, we want to stretch out our hand to her from here - to unite with her in one feeling of common sadness. We could not take one last look at his lifeless face; but we send him our farewell greetings from afar - and with a reverent feeling we commemorate our sorrow and our love on his fresh grave, into which we failed, like the Muscovites, to throw a handful of our native land! The thought that his ashes will rest in Moscow fills us with some kind of woeful satisfaction. Yes, let him rest there, in this heart of Russia, which he knew so deeply and loved so much, loved so passionately that only frivolous or short-sighted people do not feel the presence of this love flame in every word he said! But it would be inexpressibly hard for us to think that the last, most mature fruits of his genius have perished for us irrevocably, and we listen with horror to cruel rumors about their extermination ...

It is hardly necessary to speak of those few people to whom our words will seem exaggerated or even completely inappropriate ... Death has a cleansing and reconciling power; slander and envy, enmity and misunderstandings - everything falls silent before the most ordinary grave: they will not speak over Gogol's grave. Whatever the final place that history leaves behind him, we are sure that no one will refuse to repeat right now after us:

Peace be upon him, eternal memory of his life, eternal glory to his name!

I forwarded this article to one of the St. Petersburg journals; but it was precisely at that time that censorship strictness began to increase greatly for some time ... Similar "crescendo" occurred quite often and - for an outside viewer - just as unreasonable as, for example, an increase in mortality in epidemics. My article did not appear on any of the following days. Meeting the publisher on the street, I asked him what it meant? “See what the weather is,” he answered me in an allegorical speech, “and there’s nothing to think about.” “But the article is the most innocent,” I remarked. “Is it innocent, is it not,” the publisher objected, “that’s not the point; in general, the name of Gogol is not ordered to be mentioned. Zakrevsky was present at the funeral in the St. Andrew's ribbon: they cannot digest this here. Soon afterwards I received a letter from a Moscow friend filled with reproaches: “How! - he exclaimed, - Gogol is dead, and at least one magazine in St. Petersburg would respond! This silence is shameful!” In my answer, I explained - I confess, in rather harsh terms - to my friend the reason for this silence and, as a proof, I attached my forbidden article as a document. He immediately submitted it to the then trustee of the Moscow District - General Nazimov - and received permission from him to publish it in Moskovskie Vedomosti. This happened in the middle of March, and on April 16, for disobedience and violation of censorship rules, I was put under arrest for a month in the unit (I spent the first twenty-four hours in Siberia and talked with an exquisitely polite and educated police non-commissioned officer who told me about his walk in the Summer Garden and about the "scent of birds"), and then sent to live in the village. I have no intention of blaming the then government; the trustee of the St. Petersburg District, the now deceased Musin-Pushkin, presented - from a species unknown to me - the whole matter as a clear disobedience on my part; he did not hesitate to assure the higher authorities that he called me personally, and personally conveyed to me the prohibition of the censorship committee to print my article(one censor's prohibition could not prevent me - by virtue of existing regulations - from submitting my article to the court of another censor), but I never saw Mr. Musin-Pushkin and had no explanation with him. It was impossible for the government to suspect a dignitary, a confidant, of such a distortion of the truth! But it's all for the best; being under arrest, and then in the countryside, brought me undoubted benefits: it brought me closer to such aspects of Russian life that, in the ordinary course of things, would probably have escaped my attention.

Already finishing the previous line, I remembered that my first meeting with Gogol took place much earlier than I said at the beginning. Namely: I was one of his students in 1835, when he taught (!) history at St. Petersburg University. This teaching, to tell the truth, took place in an original way. Firstly, Gogol certainly missed two out of three lectures; secondly, even when he appeared on the pulpit, he did not speak, but whispered something very incoherent, showed us small engravings on steel depicting views of Palestine and other Eastern countries, and all the time he was terribly embarrassed. We were all convinced (and we were hardly mistaken) that he knew nothing about history - and that Mr. Gogol-Yanovsky, our professor (as he was called in the lecture schedule), has nothing in common with the writer Gogol, already known to us as the author of Evenings on a Farm near Dikanka. At the final exam from his subject, he sat, tied with a handkerchief, allegedly from a toothache - with a completely dead physiognomy - and did not open his mouth. Professor I.P. Shulgin asked the students for him. As I now see his thin, long-nosed figure with two ends sticking high - in the form of ears - the ends of a black silk scarf. There is no doubt that he himself was well aware of all the comedy and all the awkwardness of his position: he resigned the same year. This did not prevent him, however, from exclaiming: “Unrecognized, I ascended the pulpit - and unrecognized, I descend from it!” He was born to be a mentor to his contemporaries; but not from the pulpit.

In the previous (first) passage I mentioned my meeting with Pushkin; By the way, I will say a few words about other, now deceased, literary celebrities that I managed to see. I'll start with Zhukovsky. Living - shortly after the twelfth year - in his village in Belevsky district, he several times visited my mother, then still a girl, in her Mtsensk estate; there is even a legend that he played the role of a magician in one home performance, and I almost saw his very cap with gold stars in the pantry of his parents' house. But many years have passed since then - and, probably, the very memory of the village young lady, whom he met by chance and in passing, has been erased from his memory. In the year our family moved to St. Petersburg - I was then 16 years old - my mother took it into her head to remind Vasily Andreevich of herself. She embroidered a beautiful velvet pillow for his name day and sent me with it to his place in the Winter Palace. I had to identify myself, explain whose son I was, and present a gift. But when I found myself in a huge palace, until then unfamiliar to me; when I had to make my way along long stone corridors, climb stone stairs, now and then bumping into motionless, as if also made of stone, sentries; when I finally found Zhukovsky’s apartment and found myself in front of a three-foot red footman with galloons on all seams and eagles on the galloons, I was seized with such trepidation, I felt such timidity that, having appeared in the office where the red footman had invited me and where, because of the long the poet's own face looked at me thoughtfully and friendly, but important and somewhat astounded; with tears in his eyes, stopped as if rooted to the door and only held out and supported with both hands - like a baby at baptism - an unfortunate pillow, on which, as I now remember, was a depiction of a girl in a medieval costume, with a parrot on her shoulder. My embarrassment probably aroused a feeling of pity in Zhukovsky's good soul; he came up to me, quietly took the pillow from me, asked me to sit down, and condescendingly spoke to me. I finally explained to him what was the matter - and, as soon as I could, I rushed to run.

Even then, Zhukovsky, as a poet, lost his former significance in my eyes; but all the same, I rejoiced at our, albeit unsuccessful, meeting, and, having come home, I recalled with a special feeling his smile, the gentle sound of his voice, his slow and pleasant movements. Zhukovsky's portraits are almost all very similar; his physiognomy was not one of those that are difficult to catch, which often change. Of course, in 1834 there was no trace of that sickly young man in him, as the "Singer in the camp of Russian soldiers" seemed to the imagination of our fathers; he became a portly, almost corpulent man. His face, slightly swollen, milky, without wrinkles, breathed calmness; he held his head at an angle, as if listening and meditating; thin, thin hair rose in pigtails over a completely almost bald skull; quiet benevolence shone in the deep gaze of his dark, Chinese-style raised eyes, and on his rather large, but correctly contoured lips, there was constantly a barely noticeable, but sincere smile of benevolence and greetings. His semi-eastern origin (his mother was, as you know, a Turkish woman) was reflected in his whole appearance.

A few weeks later I was again brought to him by an old friend of our family, Voin Ivanovich Gubarev, a remarkable, typical person. A poor landowner of the Kromsky district, Oryol province, during his early youth he was in the closest connection with Zhukovsky, Bludov, Uvarov; in their circle he was a representative of French philosophy, a skeptical, encyclopedic element, rationalism, in a word, of the 18th century. Gubarev spoke excellent French, he knew Voltaire by heart and put him above everything in the world; he hardly read other writers; his mentality was purely French, pre-revolutionary, I hasten to add. I still remember his almost constant, loud and cold laugh, his cheeky, slightly cynical judgments and antics. His appearance alone condemned him to a solitary and independent life; he was a very ugly man, fat, with a huge head and mountain ash all over his face. A long stay in the provinces finally left its mark on him; but he remained a "type" to the end, and to the end, under the poor Cossack of a petty nobleman who wears oiled boots at home, he retained freedom and even elegance of manners. I do not know the reason why he did not go uphill, did not make a career for himself, like his comrades. Probably, he did not have the proper perseverance, there was no ambition: it does not get along well with that half-indifferent, half-mocking Epicureanism, which he borrowed from his model - Voltaire; but he did not recognize literary talent in himself; Fortune did not smile at him - he just faded away, died out, became a bean. But it would be interesting to trace how this inveterate Voltairian in his youth treated his friend, the future "ballade player" and Schiller's translator! A greater contradiction cannot be imagined; but life itself is nothing but a contradiction constantly conquered.

Zhukovsky - in St. Petersburg - remembered an old friend and did not forget what could please him: he gave him a new, beautifully bound collection of the complete works of Voltaire. They say that shortly before his death - and Gubarev lived for a long time - the neighbors saw him in his dilapidated hut, sitting at a wretched table, on which lay a gift from his famous friend. He carefully turned over the gold-edged sheets of his favorite book - and in the wilderness of the steppe outback, sincerely, as in the days of his youth, he amused himself with witticisms that Frederick the Great once amused himself in Sanssouci and Catherine II in Tsarskoye Selo. There was no other mind, no other poetry, no other philosophy for him. This, of course, did not prevent him from wearing a whole bunch of images and incense around his neck - and being under the command of an illiterate housekeeper ... The logic of contradictions!

I never met Zhukovsky again.

I saw Krylov only once - at the evening with one bureaucratic, but weak Petersburg writer. He sat for more than three hours motionless between two windows - and at least uttered a word! He wore a loose, shabby tailcoat and a white neckerchief; tasseled boots draped his stout legs. He leaned with both hands on his knees - and did not even turn his colossal, heavy and majestic head; only his eyes moved from time to time under the overhanging brows. It was impossible to understand what he was listening to and shaking his mustache or just So sits and "exists"? No drowsiness, no attention on this vast, straight Russian face - but only the mind chamber, but mature laziness, and at times something crafty seems to want to come out and cannot - or does not want - to break through all this senile fat ... The owner at last asked him to come to dinner. "A horseradish pig is prepared for you, Ivan Andreevich," he remarked troublesomely and as if fulfilling an inevitable duty. Krylov looked at him, half affably, half mockingly ... "So, surely a piglet?" - he seemed to utter inwardly - he stood up heavily and, shuffling heavily with his feet, went to take his place at the table.

I also saw Lermontov only twice: in the house of a noble St. Petersburg lady, Princess Sh ... oh, and a few days later, at a masquerade in the Noble Assembly on the eve of the new year, 1840. At Princess Sh ... oh, I, a very rare and unusual visitor to secular evenings, only from a distance, from the corner where I huddled, watched the poet who quickly became famous. He sat on a low stool in front of a sofa, on which, dressed in a black dress, sat one of the beauties of the capital at that time, the fair-haired Countess M.P. - an early dead, really lovely creature. Lermontov was wearing the uniform of the Life Guards Hussar Regiment; he took off neither his saber nor his gloves, and, hunched over and frowning, looked sullenly at the countess. She spoke little to him and more often turned to Count III, who was sitting next to him, also a hussar. There was something sinister and tragic in Lermontov's appearance; some kind of gloomy and unkind force, thoughtful contempt and passion emanated from his swarthy face, from his large and motionless dark eyes. Their heavy gaze strangely disagreed with the expression of almost childishly tender and protruding lips. His whole figure, squat, bow-legged, with a large head on stooped broad shoulders, aroused an unpleasant sensation; but everyone was immediately aware of the inherent power. It is known that he to some extent portrayed himself in Pechorin. The words: "His eyes did not laugh when he laughed," etc., were indeed applied to him. I remember that Count Sh. and his interlocutor suddenly laughed at something and laughed for a long time; Lermontov also laughed, but at the same time looked at both of them with some kind of offensive surprise. Despite this, it still seemed to me that he loved Count Sh ... as a comrade, and had a friendly feeling towards the countess. There was no doubt that, following the fashion of the time, he had indulged in a certain kind of Byronian genre, with an admixture of other, even worse whims and eccentricities. And he paid dearly for them! Internally, Lermontov must have been deeply bored; he was suffocating in the tight sphere into which fate had pushed him. At the ball of the Assembly of the Nobility, they did not give him rest, they constantly pestered him, took him by the hands; one mask was replaced by another, but he hardly moved from his place and silently listened to their squeak, turning his gloomy eyes on them in turn. It seemed to me at the same time that I caught on his face a beautiful expression of poetic creativity. Perhaps these verses came to his mind:

When my cold hands touch

With the careless boldness of urban beauties

For a long time untrembling hands ... etc.

By the way, I’ll say a few words about one more deceased writer, although he belongs to the “diis minorum gentium” and can no longer become along with those named above - namely, M. N. Zagoskin. He was a short friend of my father and in the thirties, during our stay in Moscow, almost daily visited our house. His "Yuri Miloslavsky" was the first strong literary impression of my life. I was in the boarding house of a certain Mr. Weidenhammer, when the famous novel appeared, the teacher of the Russian language - he is also a class warden - told my comrades and me its contents during the hours of recreation. With what devouring attention we listened to the adventures of Kirsha, the servant of Miloslavsky, Alexei, the robber Omlyash! But strange thing! "Yuri Miloslavsky" seemed to me a miracle of perfection, but I looked rather indifferently at its author, at M. N. Zagoskin. It is not far to go for an explanation of this fact: the impression made by Mikhail Nikolayevich not only failed to strengthen those feelings of worship and delight that his novel aroused, but, on the contrary, it should have weakened them. In Zagoskin there was nothing majestic, nothing fatal, nothing that affects the youthful imagination; to tell the truth, he was even rather comical, and his rare good nature could not be properly appreciated by me: This quality is irrelevant in the eyes of frivolous youth. The very figure of Zagoskin, his strange, as if flattened head, quadrangular face, bulging eyes under eternal glasses, a short-sighted and dull look, unusual movements of his eyebrows, lips, nose, when he was surprised or then simply spoke, sudden exclamations, waving his hands, a deep depression, dividing his short chin in two - everything about him seemed to me eccentric, clumsy, amusing. In addition, he had three, also rather comical, weaknesses: he imagined himself an unusual strong man; he was sure that no woman could resist him; and finally (and this was especially surprising in such a zealous patriot), he had an unfortunate weakness for the French language, which mangled without mercy, constantly mixing numbers and genders, so that he further received the nickname in our house: "Monsieur l\" article " .

With all that, it was impossible not to love Mikhail Nikolaevich for his heart of gold, for that artless frankness of character, which strikes in his writings.

My last meeting with him was sad. I visited him many years later - in Moscow, shortly before his death. He no longer left his office and complained of constant pain and aching in all members. He had not lost weight, but a deathly pallor covered his still full cheeks, giving them an all the more despondent look. The raising of the eyebrows and the goggling of the eyes remained the same; the involuntary comicality of these movements only aggravated the feeling of pity that aroused the whole figure of the poor writer, who was clearly leaning towards destruction. I talked to him about his literary activity, about the fact that in St. Petersburg circles they again began to appreciate his merits, to do him justice; mentioned the significance of "Yuri Miloslavsky" as a folk book ... Mikhail Nikolayevich's face brightened. “Well, thank you, thank you,” he said to me, “and I already thought that I was forgotten, that today's youth trampled me into the mud and covered me with a log.” (Mikhail Nikolaevich did not speak French to me, and in Russian conversation he liked to use energetic expressions.) “Thank you,” he repeated, not without emotion and feelingly shaking my hand, as if I were the reason that he was not forgotten. . I remember that rather bitter thoughts about so-called literary fame came into my head then. Inwardly, I almost reproached Zagoskin for cowardice. What, I thought, makes a man happy? But why shouldn't he rejoice? He heard from me that he had not completely died ... and after all, there is nothing worse than death for a person. Other, literary fame can, perhaps, live to the point that even this insignificant joy does not recognize. The period of frivolous praise will be followed by a period of just as little meaningful battle, and then - silent oblivion ... And who among us has the right not to be forgotten - the right to burden the memory of descendants with his name, who have their own needs, their own concerns, their own aspirations?

And yet I am glad that, quite by accident, I gave good Mikhail Nikolaevich, before the end of his life, at least instant pleasure.

Notes

TEXT SOURCES

Draft autograph, 17 sheets. and "Letter from Petersburg" - clerk's copy, 2 sheets. Stored in the Department of Manuscripts Bibl Nat, Slave 75; description see: mason, p. 76-77: photocopy - IRLI, R. I, op. 29, no. 331.

Typeset manuscript, 10 sheets. Stored in gim, f. 440, no. 1265, l. 148-157.

"Letter from Petersburg". White autograph, 2 sheets. Dated February 24, 1852. Kept in CSAOR, f. 109, op. 1852, unit ridge 92, l. 13-14.

"N. V. Gogol ”(original title“ Letters from Petersburg ”). proofreading SPb Ved. Dated February 24, 1852. Kept in CSAOR, f. 109, op. 1852, unit ridge 92, l. 16.

"Letter from Petersburg". Publication in Moscow Ved, 1852, No. 32, March 13. Dated February 24, 1852 Signed "T...... b"

T, Soch, 1869, part 1, p. LXIX-LXXXIX.

T, Soch, 1874, h. 1, p. 70-90.

T, Soch, 1880, vol. 1, p. 63-83.

Printed by text T, Soch, 1880 with the elimination of obvious typographical errors not noticed by Turgenev, as well as with the following corrections according to all other sources:

Page 63, line 18:"actor who performed" instead of "performed".

Page 70, line 19:"beautifully intertwined" instead of "beautifully intertwined".

Page 71, line 20:"rare and unusual" instead of "rare, unusual".

Page 71, line 25:"blond" instead of "white-haired".

The essay "Gogol" was conceived in 1868, which is clear from the plan written on fol. 1 draft autograph of the essay “Instead of an introduction” (see above, p. 322). However, the first, and then indirect, mention of the work on the essay is contained in a letter to P. V. Annenkov dated May 24 (June 5), 1869: “I need a copy of my letter on the occasion of Gogol’s death.” Based on this letter, it can be assumed that work on a rough autograph in the twentieth of May 1869 had already begun. It is difficult to say exactly when the essay was completed: neither the draft autotraffic nor the typesetting manuscript is dated. There is also no mention of this work in Turgenev's correspondence. But since the essay appeared in the first part of the Works, published in November 1869, it remains to be assumed that work on it was most likely completed in July-August, especially since on September 20 (October 2) Turgenev had already sent Salaev the last excerpt from " Literary and Worldly Memoirs" - an essay "About" Fathers and Sons "".

Draft autograph 1* has a large number of inserts made in the margins, crossed out phrases or parts of phrases, as well as individual words that are crossed out more than once, sometimes replaced by others. Turgenev made especially large edits in the sections devoted to Zhukovsky and Zagoskin. On the other hand, some lines included in the final text appeared at later stages of the work. So, the words “this musty and insipid spirit came from there,” said about the influence on Gogol of “persons of the highest flight”, are not in the draft autograph. There are no words “He himself was “caught up””, characterizing Khlestakov’s lies. There are also no lines in the draft autograph that refer to Turgenev's stay under arrest.

However, the differences between the draft autograph and the final text are mostly not in the absence of certain phrases, but in what the first layer of the autograph contains. In this regard, the first section of the essay, dedicated to Gogol, is of considerable interest. So, in a draft autograph, instead of the words: “his sloping, smooth, white forehead still blew with the mind,” it was originally written: “the sloping white forehead was still beautiful and even wrinkles were not noticed on it.” And then the words closer to the final text appeared: “the sloping white forehead still shone with the mind” ( T, PSS and P, Works, vol. XIV, variant to p. 65, lines 7-8). Recalling his first trip to Gogol, Turgenev initially wrote in a draft autograph “as to a patient”, and then, in the same draft, he corrected these words to “as to an extraordinary, brilliant person who had something in his head” (there same, variant to p. 65, lines 25-27), which significantly changed the meaning of the whole phrase. Initially, Turgenev expressed his attitude towards censorship and Gogol's position on this issue with greater sharpness (ibid., variant to p. 66, lines 25-28).

The text of the typesetting manuscript differs from the final one in minor discrepancies.

The surviving proofreading of the obituary article “N. V. Gogol ”(original title“ Letters from Petersburg ”), typed for SPb Ved, as well as a white autograph entitled "Letter from Petersburg", intended by Turgenev already for Moscow Ved, somewhat different from the final text.

The most significant difference in proofreading SPb Ved from the final text - the presence of a footnote in it: “They say that Gogol, eleven days before his death, when he did not seem to be sick yet, began to say that he would die soon, and burned all his papers at night, so that now after him there is not a single unprinted line left" and the phrase (also available in a white autograph): "If such people are found, we feel sorry for them, sorry for their misfortune" 2 * after the word "inappropriate".

In this essay, Turgenev recalls literary meetings different years. And not only with Gogol - they were, of course, the most significant. He also talks about his acquaintance with M. N. Zagoskin during his childhood and about his meeting with this writer shortly before his death: about his acquaintance with Zhukovsky upon arrival in St. Petersburg to enter the capital's university; about the only brief meeting with Krylov. Finally, we are talking about two meetings with Lermontov, which, unfortunately, did not lead to a personal acquaintance of Turgenev with his great contemporary.

Turgenev considered himself a student and follower of Gogol. In his literary-critical articles, as well as in works of art, he constantly spoke out in favor of the development of the Gogol trend, considering it to be the leading one in Russian literature. Exiled from St. Petersburg to Spasskoe-Lutovinovo for an obituary article about Gogol, Turgenev read and reread his works during a year and a half of forced seclusion (see letter to S. T., I. S. and K. S. Aksakov dated 6 (18) June 1852) 3*.

In 1855, Turgenev argued with representatives of "pure art", who opposed Pushkin's direction in Russian literature to Gogol's.

There is no doubt that Gogol also appreciated Turgenev as a writer. As early as September 7, 1847, after the first essays appeared in Sovremennik, which later compiled the book The Hunter’s Notes, Gogol wrote to P.V. as a writer, I partly know him: as far as I can judge from what I have read, talent is in him wonderful and promises great activity in the future" ( Gogol, vol. 13, p. 385). This is also evidenced by S. P. Shevyrev in a letter to M. P. Pogodin in 1858: “I have written evidence about Turgenev from Gogol<...>He loved him very much and hoped for him. Barsukov, Pogodin, book. 16, p. 239-240).

Zhukovsky's poetry played a significant role in Turgenev's literary development during his childhood and early youth. In V. P. Turgeneva's letters to her son, Zhukovsky's name is frequently encountered with quotations from his works. During the years of his stay in the Moscow boarding school, Turgenev intensively read Zhukovsky, knew by heart many lines from his messages and ballads. This is known, in particular, from his letters to his uncle, N. N. Turgenev, relating to March - April 1831 (see: present ed., Letters, vol. 1, pp. 119-130).

Lermontov was one of Turgenev's favorite poets. His poetry had an impact on Turgenev's early work - poems and poems. "Hero of Our Time" great importance for the formation of Turgenev's prose of the 1840s 6*.

Turgenev's preface to the French translation of the poem "Mtsyri" dates back to 1865 (present ed., vol. 10, p. 341).

In 1875, Turgenev wrote a review of the English translation of The Demon by A. Stephen (present ed., vol. 10, p. 271).

In the reviews that appeared in the press on part 1 of Turgenev's Works, the essay "Gogol" was not given much attention. D. Sviyazhsky (D. D. Minaev), speaking sharply ironically about Literary Memoirs in general, reproached Turgenev, in particular, for his attention to detail (description of Gogol's costume). In conclusion, he noted, however, that "the chapter on Gogol is still the most curious in the memoirs of Mr. Turgenev" (Delo, 1869, No. 12, p. 49). An essay in the journal Bibliographer was severely assessed, which stated: “... where Mr. Turgenev describes a person in one external way, there this person is in front of the reader, as if alive; where he goes into discussions about this person, there are only phrases like: “A great poet, a great artist was in front of me, and I looked at him, listened to him with reverence - even when I did not agree with him” ”(Bibliographer, 1869, No. 3, December, p. 14).

Page 57. brought me together~Shchepkin. — Mikhail Semenovich Shchepkin (1788-1863) - famous actor, friend of Gogol; was closely acquainted with Turgenev. M. A. Shchepkin, according to M. S. Shchepkin, reports: “... at three o'clock, Ivan Sergeevich and I came to Gogol. He received us very cordially; when Ivan Sergeevich told Gogol that some of his works, translated by him, Turgenev, into French and read in Paris, made a great impression, Nikolai Vasilyevich was noticeably pleased and, for his part, said a few courtesies to Turgenev ”(Shchepkin M. A. M S. Shchepkin, 1788-1863, His Notes, Letters, Stories, Materials for Biography and Genealogy, St. Petersburg, 1914, p. 374).

... in Moscow, on Nikitskaya~with Count Tolstoy.- On Nikitsky Boulevard (now 7 on Suvorovsky Boulevard). - Count Alexander Petrovich Tolstoy (1801-1873) was one of the most reactionary acquaintances of Gogol. Correspondence and conversations with him, which had an impact on Gogol, affected a number of articles in the book Selected passages from correspondence with friends.

... stretching out his head~from public curiosity.- L. I. Arnoldi in the essay “My Acquaintance with Gogol” points to the same fact: “Many in the stalls noticed Gogol, and the lorgnettes began to address our box. - Gogol, apparently, was afraid of some kind of demonstration from the public, and, perhaps, challenges ... "( Rus Vestn, 1862, No. 1, p. 92).

F.- Evgeny Mikhailovich Feoktistov (1829-1898) - writer, journalist and historian, who in the 1850s collaborated in Moskovskie Vedomosti, Sovremennik and Otechestvennye Zapiski; later head of the Main Directorate for the Press (see about him: T, PSS and P, Letters, vol. II, index of names, p. 694).

I met him twice then~E-noy.- This refers to Avdotya Petrovna Elagina (1789-1877), by her first husband Kireevskaya, niece of V. A. Zhukovsky, mother of P. V. and I. V. Kireevsky, with whom Turgenev was well acquainted (the Kireevsky estate was located not far from Belev ). Elagina's literary salon was widely known in Moscow in the 1830s and 1840s.

Page 58. I myself would not mention Correspondence with Friends, since I could not say anything good about it.- Gogol's book "Selected passages from correspondence with friends" was published in 1847. A number of Turgenev's letters contain indirect, but always negative reviews about it. In particular, on April 21 (May 3), 1853, Turgenev wrote to Annenkov, referring to the second volume of Dead Souls, that in it Gogol sought to mitigate those "cruelties" that were inherent in the first volume of the poem, and wanted to "make amends for them in the sense of "Correspondence".

Page 59. "Si servi ~ frementi"... - It has not been established which of the Italian poets the above verse belongs to.

... persons of the highest flight, to whom most of the "Correspondence" is devoted ...- This refers to Count A.P. Tolstoy (see note to p. 57), Countess Louise Karlovna Vielgorskaya, wife of Mikh. Yu. Vielgorsky, Alexandra Osipovna Smirnova, born. Rosset (1809-1882) - the wife of the Kaluga, then St. Petersburg governor N. M. Smirnov. Turgenev had a very negative attitude towards A. O. Smirnova (see letter to P. V. Annenkov dated October 6 (18), 1853). In chapter XXV of "Fathers and Sons", recalling A. O. Smirnova, the writer put the following words into Bazarov's mouth: "Since I've been here, I feel nasty, as if I had read Gogol's letters to the Kaluga governor" (present. ed., vol. 7, p. 161).

... foreign edition ~ in apostasy from former beliefs.- This refers to the article by A. I. Herzen "On the Development of Revolutionary Ideas in Russia", which was published as a separate pamphlet in French in 1851 in Paris. Arguing with the Slavophiles, Herzen wrote about Gogol: “He began to defend what he had previously destroyed, to justify serfdom, and in the end threw himself at the feet of the representative of“ goodwill and love ”. Let the Slavophils think about the fall of Gogol<...>From Orthodox humility, from self-denial, which dissolved the personality of a person in the personality of a prince, to the adoration of an autocrat is only a step. Herzen, vol. 7, p. 248). Gogol, who was painfully experiencing the fiasco of Selected passages from correspondence with friends, was very hurt by Herzen's recall.

... the publisher would give him if he threw it away ... ~ those that are written to secular ladies ...- We are talking, in particular, about letters to Princess V. N. Repnina, N. N. Sheremetyeva and A. O. Smirnova, first published in vols. 5 and 6 Works and letters of N. V. Gogol, ed. P. A. Kulish, St. Petersburg, 1857.

Page 60. ... it was about the need to obey the authorities, etc. - Probably, Gogol's article "On the Teaching of World History" (1832) is meant.

Two days later, the reading of The Inspector General took place ...- G.P. Danilevsky in the essay “Acquaintance with Gogol” indicates that this reading took place later, on November 5, 1851, seeing an inaccuracy in Turgenev ( IV, 1886, No. 12, p. 484).

Page 62. ... not all the actors who participated in the "Inspector General" came to the invitation ~ Not a single actress came either.- According to G. P. Danilevsky, S. T. and I. S. Aksakovs, S. P. Shevyrev, I. S. Turgenev, N. V. Berg, M. S. Shchepkin, P. M. Sadovsky, S. V. Shumsky (ibid.).

Page 63. ... a very young, but already unusually importunate writer ...- We are talking about Grigory Petrovich Danilevsky (1829-1890) - a novelist, whose work met with a negative attitude from Turgenev (see his review of Danilevsky's "Slobozhan" - present ed., vol. 4, pp. 523, 677) and progressive criticism of the 1850s and 1860s.

... where Khlestakov is lying ...- "Inspector", the third act, yavl. VI.

... at the mercy of an uninvited writer ~ rubbed himself into his office after him. Turgenev was wrong. Danilevsky wrote to V. P. Gaevsky: Gogol “invited me, Turgenev and some actors to the evening on the third day and read us his The Inspector General, and then, when everyone left, he read with me a new Zaporizhzhya Duma, written here by me (in rhymes), corrected it himself, and until three o'clock in the morning spoke with me about literature and about many, many things" ( GPB, f. 171, archive of V.P. Gaevsky, No. 102, l. 11-11 about. - said E. V. Sviyasov). Later, in 1872, Ya. P. Polonsky wrote to Turgenev that G. P. Danilevsky was going “sooner or later<...>take revenge<...>for slander (that is, for Gogol's story)" ( links, vol. 8, p. 168).

Page 64. ... noticed I. I. Panaev ...- Ivan Ivanovich Panaev (1812-1862) - novelist, feuilletonist, satirical poet, co-editor of the Sovremennik magazine, memoirist.

He died, smitten in the prime of his life...- Gogol died before reaching the age of 43.

Page 65. ... the most mature fruits of his genius~ rumors of their extermination...- On March 4, 1852, Turgenev wrote to P. Viardot: “Ten days before his death, he<Гоголь — ed.> betrayed everything to burning, and, having committed this moral suicide, took to his bed, so as not to get up again" ( T, nouv corr ined, t. 1, p. 64; Zilberstein I. Turgenev. finds recent years. - Literary newspaper, 1972, No. 17, April 26).

Page 66. I forwarded this article to one of the St. Petersburg magazines...- It's about S. Petersburg Vedomosti” (see letter to E. M. Feoktistov dated February 26 (March 9), 1852), in which Turgenev’s article about Gogol did not appear, as it was banned by St. Petersburg censorship.

Zakrevsky ~ attended ...- Arseny Andreevich Zakrevsky (1783-1865) - Moscow military governor-general from 1848 to 1859. E. M. Feoktistov informed Turgenev on February 25 (March 8), 1852: “All Moscow was decisively at the funeral<...>Zakrevsky and others were in full uniforms ... "( Lit Nasl, v. 58, p. 743). The appearance of Zakrevsky was not, however, a sign of respect for the memory of Gogol, since, according to a contemporary, he never read it ( Barsukov, Pogodin, book. 11, p. 538).

... from Moscow~ a letter full of accusations...- In the letters of E. M. Feoktistov and V. P. Botkin that have come down to us, with whom Turgenev shared his feelings and thoughts caused by Gogol's death, there are no appeals to Turgenev with a request to write an article about Gogol.

... buddy~ banned article.- On February 26 (March 9), 1852, Turgenev wrote to E. M. Feoktistov that his “a few words” about Gogol’s death, written by him for “S. Petersburg Vedomosti”, he sends him to Moscow “with this letter, in the unknown whether they will be missed and whether the censorship will distort them.”

... trustee of the Moscow district - General Nazimov ...- Vladimir Ivanovich Nazimov (1802-1874) was also the chairman of the Moscow Censorship Committee (1849-1855).

... was planted~in part...- Turgenev was arrested and imprisoned "on the congress 2nd Admiralteyskaya part", located near Theater Square, at the corner of Officerskaya Street and Mariinsky Lane; the house has not been preserved, it stood on the site now occupied by houses 30 and 28 along Dekabristov Street (see: Literary memorable places of Leningrad. L., 1976, p. 356).

... sent to live in the village.- Turgenev was released from arrest on May 16 (28) and went into exile in Spasskoe-Lutovinovo (via Moscow) on May 18 (30), 1852.

... the late Musin-Pushkin~and had no explanation for it.- Mikhail Nikolayevich Musin-Pushkin (1795-1862) - Chairman of the St. Petersburg Censorship Committee and Trustee of the St. Petersburg Educational District. In his diary, the censor A. V. Nikitenko on March 20, Art. Art. 1852 noted that even before the submission of Turgenev's article to censorship, “the chairman of the censorship committee announced that he would not let go of articles in praise of Gogol, the ‘lackey writer’. He also forbade the “S. P<етербургских>Vedomosti" article, but without any formalities, so this prohibition could not be considered official. Turgenev, seeing this as simply a whim of the chairman, sent his article to Moscow, where it appeared in print. The order says that “despite the prohibition announced to the landowner Turgenev, he dared,” etc. This announcement was not made. Turgenev was not asked for any explanation; no one interrogated him, but directly punished him. They say that Bulgarin, by his influence on the chairman of the censorship committee and by his suggestions to him, is most guilty of all ... "( Nikitenko, vol. 1, p. 351).

Page 67. ... he taught (!) history at St. Petersburg University.- Gogol was invited to teach history, ancient and medieval, in 1834.

... that he does not understand anything in history .... - This opinion of Turgenev is unfair. Gogol knew and loved history, but did not have the gift of a teacher and lecturer. In addition, it should be borne in mind that his lectures met with organized opposition from the reactionary professors (see: Mordovchenko N. I. Gogol at St. No. 46, pp. 355-359, Aizenshtok I. Ya. V. A., Stepanov A. N. Gogol in Petersburg, L., 1961, pp. 128-139).

Professor I.P. Shulgin asked the students for him.- Ivan Petrovich Shulgin (1795-1869) - professor at St. Petersburg University, author teaching aids on general and Russian history. N. M. Kolmakov, who studied with Turgenev, recalled: “Gogol’s departure and the abandonment of his lectures were unexpected and affected us very unfavorably. Professor Shulgin at the exam asked us such questions that were not at all included in the program of Gogol's lectures<...>Shulgin did not like Turgenev's answer<...>he began to ask Turgenev other questions about chronology and, of course,<...>achieved his goal: Turgenev made a mistake and received a disapproving mark. Therefore, his candidacy smiled "( Rus St, 1891, No. 5, p. 461-462). It was from Shulgin that Turgenev then received “verbal permission” to attend lectures again (see his petition to the rector of St. Petersburg University dated May 11 (23), 1837 - present ed., Letters, vol. 1, p. 342). For more on this, see: V. A. Gromov, Gogol and Turgenev. 1. Turgenev - listener of Gogol's lectures on history. — T sat, issue 5, p. 354-356.

"Unrecognized, I ascended the pulpit - and unrecognized I descend from it!" — Inaccurate quote from Gogol's letter. Gogol wrote to M.P. Pogodin on December 6 (18), 1835, that he “spoiled with the university”, emphasizing: “Unrecognized I ascended the department and unrecognized I leave it” (Works and letters of N.V. Gogol Published by P. A. Kulish, St. Petersburg, 1857, vol. 5, p. 246).

Page 68. I'll start with Zhukovsky. Living - shortly after the twelfth year~ in Belevsky district~ my mother ~ in her Mtsensk estate ... - V. A. Zhukovsky’s visits to V. P. Turgeneva in Spassky-Lutovinovo could, apparently, be in the summer and autumn of 1814. At that time, the poet lived in Muratov (May - June), the estate of E. A. Protasova, 30 versts -ti from Spassky, then (from September until the end of the year) - At A.P. Kireevskaya in Dolbin, 40 miles from the estate of Turgenev's mother (see: Chernov Nikolai. Chapter from childhood. - Literary newspaper, 1970, No. 29 , July 25).

... to him in the Winter Palace.- V. A. Zhukovsky lived in the Winter Palace from the end of the 1820s as the educator of the heir, the future Alexander II.

Page 69. ... seemed to the imagination of our fathers "A singer in the camp of Russian soldiers" ...- Zhukovsky wrote this poem in 1812, that is, when he was 29 years old.

... an old friend of our family ~ Gubarev~ in the closest connection with Zhukovsky ...- V. I. Gubarev and his sister A. I. Lagriva (Lagrivaya) (see this volume, p. 476) were close acquaintances of V. P. Turgeneva. Probably, it was V. I. Gubarev who brought Zhukovsky to Spasskoye, who once studied with the poet and brothers A. I. and N. I. Turgenev at the Moscow University Noble Boarding School (see: Diaries of V. A. Zhukovsky. St. Petersburg, 1903, p. 350). Later, like his father, I. A. Gubarev, he was on friendly terms with famous figure freemasonry I. V. Lopukhin. Voltairianism, perhaps, coexisted in V. I. Gubarev with sympathy for Freemasonry. According to a modern researcher, in 1875 Turgenev endowed one of his heroes of the story "The Hours" with the features of the internal and external appearance of V.I. Gubarev - Uncle Yegor, an exiled Voltairian (in the original version of the Freemason). - See: Chernov N. Chapter from childhood).

Page 70. Zhukovsky~ gave him a new ~ collection of the complete works of Voltaire.- On July 4, 1835, Gubarev wrote to Zhukovsky: “I thank you very much for<...>Voltaire's gift; - I alone in this world will keep feelings of true respect for you until the grave "( IRLI, 28024 / SS1b. 70).

... once Frederick the Great in Sanssouci...- Frederick II (1712-1786) - King of Prussia since 1740. Sans-Souci (Sans-Souci) - a palace and park in Potsdam, near Berlin, the permanent residence of Frederick II.

... from one bureaucratic, but weak St. Petersburg writer.- Perhaps we are talking about V. I. Karlgof (see note on p. 334).

... didn't even turn~ under drooping eyebrows.- Turgenev created a similar, but more detailed, verbal portrait of Krylov with more details a little later, in 1871, in the preface to the translation of his fables into English language carried out by V. R. Ralston (present ed., vol. 10, p. 266).

Page 71. At Princess Sh... oh...- We are talking about Princess Sofia Alekseevna Shakhovskaya, born. Countess Musina-Pushkina (1790-1878). With her husband, Prince Ivan Leontievich Shakhovsky, general, participant Patriotic War 1812, she lived in two-story house on Panteleymonovskaya street (now 11 on Pestelya street; the 3rd and 4th floors were built on in the 1860s 8*). The Shakhovskys are the neighbors of the Turgenevs; their estate - Bolshoe Skuratovo, Chernsky district - was located not far from Spassky-Lutovinov (see: Puzin N. P. Turgenev and N. N. Tolstoy. - T sat, issue 5, p. 423). In one of the letters (to M.N. and V.P. Tolstoy dated February 14 (24), 1855), Turgenev mentioned the name of S. A. Shakhovskaya’s husband: “our neighbor Prince I. L. Shakhovskaya” ( T, PSS and P, Letters, vol. II, p. 261-262).

... at a masquerade in the Noble Assembly on the eve of the new year, 1840.- On the night of December 31, 1839 to January 1, 1840, there was no ball or masquerade at all in the Nobility Assembly. It remains to be assumed that Turgenev “saw Lermontov at a masquerade in December 1839, as he writes, but on some other day and in another place” (Gershtein E. The fate of Lermontov. M., 1964, pp. 77, 78).

... Countess M. P. ...- Countess Emilia Karlovna Musina-Pushkina, born. Shernval (1810-1846), to whom Lermontov's poem "Countess Emilia - whiter than a lily" (1839) is dedicated; wife of Count V. A. Musin-Pushkin, brother of S. A. Shakhovskaya. Both of them (Shakhovskaya and Musina-Pushkina), like Turgenev, were on the steamer "Nikolai I", making cruise, tragically ended on May 18, 1838 (see: SPb Ved, 1838, No. 84, April 19; Turgenev in Heidelberg in the summer of 1838. From the diary of E. V. Sukhovo-Kobylina. Publication by L. M. Dolotova. — Lit Nasl, v. 76, p. 338-339). Turgenev described this trip in the essay “Fire at Sea” (this volume, p. 293).

... to Count Sh ... who was sitting next to him ...- This refers to Andrei Pavlovich Shuvalov (1816-1876), count, Lermontov's comrade in the Life Guards Hussars and in the "circle of sixteen."

There was something sinister and tragic in Lermontov's appearance. ~ childishly tender and protruding lips ~ everyone was immediately aware of the inherent power.– This wonderful verbal portrait of Lermontov probably reflected not only Turgenev’s personal impressions, but also the opinions of many contemporaries (oral and printed), who often noted the complexity of the poet’s nature with its contrasts and opposites; “connection of the unconnected” in it (Udodov B. T. “Consonance of the words of the living.” - In the book: Lermontov M. Yu. Selected. Voronezh, 1981, p. 17).

Page 72. When my cold hands touch...- Turgenev quotes lines 8-10 from Lermontov's poem “How often! surrounded by a motley crowd" (1840).

He was a short buddy~ visited our house.- See also Turgenev's letter to S. T. Aksakov dated January 22 (February 3), 1853, which is repeated almost verbatim in this essay.

His "Yuri Miloslavsky"~ strong literary impression... The novel by M. N. Zagoskin (1789-1852) “Yuri Miloslavsky, or the Russians in 1612” was published in 1829 in three volumes. On January 22 (February 3), 1853, Turgenev wrote to S. T. Aksakov: “... as for Miloslavsky, I knew it by heart; I remember I was in a boarding house in Moscow<...>and in the evenings our overseer told us the contents of "Yu<рия>M<илославского>“. It is impossible to portray to you the absorbing and absorbed attention with which we all listened. Turgenev told L.N. Maikov about the same on March 4, 1880 ( Rus St, 1883, No. 10, p. 204).

I was in the boarding house of a certain Mr. Weidenhammer when the famous novel appeared...- Turgenev was placed in this boarding school in the autumn or winter of 1827/28 and stayed there, apparently, until the late summer of 1830 (see this volume, p. 442).

Page 73. In addition, he was followed by three~ comic weakness...- Turgenev told L. N. Maikov about these same “weaknesses” of M. N. Zagoskin on March 4, 1880 ( Rus St, 1883, No. 10, p. 205).

. Moscow News, 1852, March 13th, No. 5 32, pp. 328 and 329.

With regard to this article (about it at the same time someone quite rightly said that there is no rich merchant whose death the magazines would not have responded with great fervor) I recall the following: one very high-ranking lady - in St. I was subjected to for this article, it was undeserved - and in any case too severely, cruelly ... In a word, she passionately interceded for me. “But you don’t know,” someone reported to her, “in his article he calls Gogol a great man!” - "Can't be!" - "Trust me". - "A! in that case I say nothing: je regrette, mais je comprends qu\"on ait du sevir.<я сожалею, но я понимаю, что следовало строго наказать (fr.) >

. "A Hero of Our Time", p. 280. Lermontov's Works, ed. 1860

junior god ( lat.)

The legend of his strength even spread abroad. At one public reading in Germany, to my surprise, I heard a ballad in which it was described how Hercules Rappo arrived in the capital of Muscovy and, giving performances at the theater, challenged everyone and defeated everyone; how suddenly, among the spectators, unable to bear the disgrace of his compatriots, der russische Dichter rose up; Stehet auf der Zagoskin! (Russian writer; Zagoskin gets up!) (German) (with emphasis on kin) - how he fought Rappo and, having defeated him, retired modestly and with dignity.

1* For a set of options for draft and white autographs, see: T, PSS and P, Works, vol. XIV, p. 332-342.

2* In the copy of the "Letter from Petersburg", kept in TsGIA(f. 777, op. 2, 1852, l. 3), in correspondence between the St. Petersburg and Moscow censorship departments, - "unfortunate" (see: Garkavi A. M. To the text of Turgenev's letter about Gogol. - Uch. Journal of Leningrad State University, 1955, No. 200. Series of philological sciences, issue 25, p. 233).

3* See also: Nazarova LN Turgenev about Gogol. - Russian Literature, 1959, No. 3, p. 155-158.

4 * Zhitova, With. 27; Malysheva I. Mother of I. S. Turgenev and his work. According to unpublished letters of V.P. Turgeneva to her son. — Russian thought, 1915, book. 6, p. 105, 107.

5* See: I. N. Rozanov, Echoes of Lermontov. - In the book: Wreath to Lermontov. Anniversary collection. M.; Pg., 1914, p. 269; Orlovsky S. Lyrics of young Turgenev. Prague, 1926, p. 171; Gabel M. O. The image of a contemporary in the early work of I. S. Turgenev (poem "Conversation"). - Ucheni notes of Kharkiv Derzh. Library Institute, no. 4. Nutrition of literature. Kharkiv, 1959, p. 46-48. For a list of references, see also: Lermontov Encyclopedia. M., 1981, p. 584.

6* See: Nazarova L. Turgenev and Lermontov. — Yezik and literature. Sofia, 1964, No. 6, p. 31-36; her own: On Lermontov's traditions in the prose of I. S. Turgenev. — Problems of the theory and history of literature. Collection of articles dedicated to the memory of Professor A. N. Sokolov. M., 1971, p. 261-269.

7* See also: Rabkina N. I. S. Turgenev in Elagina's salon. - Questions of Literature, 1979, No. 1, p. 314-316.

8 Reported by B. A. Razodeev.

In 1832, it seems like in the spring, when we lived in Sleptsov's house on Sivtsev Vrazhek, Pogodin brought to me, for the first time and quite unexpectedly, Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol. "Evenings on a Farm near Dikanka" were read long ago, and we all admired them. However, I read "Dikanka" by accident: I got it from a bookstore, along with other books, to read aloud to my wife, on the occasion of her illness. One can imagine our joy at such a surprise. We did not suddenly find out the real name of the writer; but Pogodin went to Petersburg for some reason, found out there who Rudy Panko was, got to know him and brought us the news that Gogol-Yanovsky had written Dikanka. So this name was already known to us and precious.On Saturdays they constantly dined with us and spent my short evenings

buddies. On one of these evenings, in my study, located on the mezzanine,

I played cards in a quadruple boston, and three people who did not play were sitting around

table. The room was hot, and some, including myself, sat without

tailcoats. Suddenly Pogodin, without any prior notice, entered the room with

unknown to me, a very young man, came straight up to me and said:

"Here's Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol!" The effect was strong. I am very

became embarrassed, rushed to put on his frock coat, muttering empty words of vulgar

recommendations. At any other time I would not have met Gogol in this way. All mine

guests (there were P. G. Frolov, M. M. Pinsky and P. S. Shchepkin 52 -

I don’t remember the others) were also somehow puzzled and silent. The reception was not

cold but awkward. The game stopped for a while; but Gogol and Pogodin

they begged me to continue the game, because there was no one to replace me. Soon,

however, Konstantin 53 ran up, rushed to Gogol and spoke to

him with great feeling and fervor. I was very happy and distracted

continued the game, listening with one ear to the words of Gogol, but he spoke

quiet and I didn't hear anything.

Gogol's outward appearance was then completely different and disadvantageous for him:

crest on the head, smoothly trimmed temples, shaved mustache and chin,

large and heavily starched collars gave a completely different

the physiognomy of his face: it seemed to us that there was something khokhlatsky and

roguish. In Gogol's dress, there was a noticeable pretension to panache. I have

I remember that he was wearing a motley light waistcoat with a large chain.

We still have portraits depicting him in his then form, donated

subsequently to Konstantin by Gogol himself 54.

Unfortunately, I do not remember at all my conversations with Gogol in the first

our date; but I remember that I often spoke to him. An hour later he left

saying that he would visit me one of these days, some early in the morning, and ask

take him to Zagoskin, whom he really wanted to meet and

who lived very close to me. Konstantin also does not remember his conversations

with him, more than what Gogol said about himself, that he was formerly a fat man, and

now sick; but he remembers that he behaved unfriendly, carelessly and somehow

condescendingly, which, of course, was not, but it might seem so. He doesn't

I liked the manners of Gogol, who made everyone, without exception,

unfavorable, unsympathetic impression. There was no way to pay a visit to Gogol

opportunities, because they did not know where he left off: Gogol did not want this

say.

In a few days, during which I have already warned

Zagoskin that Gogol wants to meet him and that I will bring him to him,

Nikolai Vasilyevich came to me quite early. I contacted him with

sincere praise of his "Dikanka"; but, apparently, my words seemed to him

ordinary compliments, and he took them very dryly. In general, it had

something repulsive, which did not allow me to be sincerely infatuated and

outpourings of which I am capable to excess. At his request, we soon went

walk to Zagoskin. On the way, he surprised me by complaining about his

illness (I did not know then that he had spoken to Konstantin about this) and even said,

that is terminally ill. Looking at him with astonished and incredulous eyes,

because he seemed to be healthy, I asked him, "But why are you sick?" He

answered vaguely and said that the cause of his illness was in the intestines.

Dear conversation was about Zagoskin. Gogol praised him for his gaiety, but said,

that he does not write what he should, especially for the theatre. I'm flippant

objected that we have nothing to write about, that in the world everything is so monotonous,

smooth, decent and empty that

Even nonsense is funny

You will not meet in you, empty light 55, -

But Gogol looked at me somehow significantly and said that "this

it is not true that the comic is hidden everywhere, that, living in the midst of it, we do not see it;

but what if the artist transfers it to art, to the stage, then we ourselves are above

we will wallow with laughter and marvel that we did not notice him before."

Maybe he didn't put it exactly like that, but the idea was exactly the same. I

was puzzled by it, especially because he did not expect to hear it from Gogol.

From the words that followed, I noticed that Russian comedy greatly interested him and that

he has his own original view of her 56. I must say,

that Zagoskin, who had also read "Dikanka" long ago and praised it, at the same

did not fully appreciate the time; and in the descriptions of Ukrainian nature I found

unnaturalness, pomposity, enthusiasm of the young writer; he found

everywhere there is an incorrectness of the language, even illiteracy. The last one was very

funny, because Zagoskin could not be accused of great literacy. He

was even offended by our superfluous, exaggerated, in his opinion,

praise. But in his good nature and in his human pride he is pleased

it was that Gogol, praised by all, hastened to come to him. He accepted it

with open arms, with cries and praises; taken several times

kiss Gogol, then rushed to hug me, hit me in the back with his fist, called

hamster, gopher, etc., etc.; in a word, he was quite amiable in his own way.

Zagoskin talked incessantly about himself: about his many occupations, about

countless books he read, about his archaeological works,

about his stay in foreign lands (he was not further than Danzig), that he traveled

up and down the whole of Rus', etc., etc. Everyone knows that this is complete nonsense and

that only Zagoskin sincerely believed him. Gogol understood this at once and spoke with

the owner, as if he had lived with him for a century, completely at the right time and in moderation. He turned

to the bookcases... Then a new story began, but for me it's already an old story:

Zagoskin began to show off and show off books, then snuffboxes and,

finally, boxes. I sat silently and amused myself at this scene. But to Gogol she

got bored pretty soon: he suddenly took out his watch and said that it was time for him to go,

promised to run again somehow and left.

"Well," I asked Zagoskin, "how did you like Gogol?" -

"Oh, how cute," shouted Zagoskin, "cute, modest, yes,

brother, smart girl!"... and so on and so forth; but Gogol said nothing, except for the most

everyday, vulgar words.

On this passage of Gogol from Poltava to Petersburg, our acquaintance did not

became close. I don’t remember how long Gogol was in Moscow again

passing through, for the shortest time 57; was with us and again asked

me to go with him to Zagoskin, to which I readily agreed. We were at

Zagoskin also in the morning; he still received Gogol very cordially and

gracious in his own way; and Gogol also behaved in his own way, that is, he spoke

about perfect trifles and not a word about literature, although the owner spoke about

her more than once. Nothing remarkable happened, except that

Zagoskin, showing Gogol his folding armchairs, pinched both my hands in such a way

springs that I screamed; but Zagoskin was taken aback and did not suddenly release me from

my plight, in which I looked like I was stretched out for torture

person. From this fun, my hands hurt for a long time. Gogol didn't even smile.

but subsequently he often recalled this incident and, without laughing himself, so skillfully

he told me that he made everyone laugh to tears. Generally in his jokes

there were a lot of original techniques, expressions, warehouse and that special

humor, which is the exclusive property of Little Russians; hand over

them impossible. Subsequently, by countless experiments, I was convinced that

repetition of Gogol's words, from which the listeners wallowed with laughter when he

I said them myself, - did not produce the slightest effect when I said them

or someone else.

And during this visit, our acquaintance with Gogol did not move forward: but,

it seems that he met Olga Semyonovna and Vera 58. In 1835

In the year 1959 we lived at the Hay Market, in the house of Stürmer. Gogol between

those already managed to issue "Mirgorod" and "Arabesques". His great talent turned out to be

full strength. Fresh, charming, fragrant, artistic were the stories in

"Dikanka", but in the "Old-world landowners", in "Taras Bulba" he already appeared

a great artist with deep and important meaning. Konstantin and I, my family

and all people capable of feeling art were completely delighted with

Gogol. It must be told the truth that in addition to sworn lovers of literature in

all walks of life, young people appreciated Gogol better and sooner. Moscow

students all came from him in admiration and were the first to distribute in Moscow

a loud rumor about a new great talent.

One evening we were sitting in the box of the Bolshoi Theatre; suddenly dissolved

door, Gogol came in, and with a cheerful, friendly air, such as we never

saw, held out his hand to me with the words: "Hello!" Nothing to say how we

were amazed and delighted. Konstantin, who almost understood more than anyone else

the meaning of Gogol, forgot where he was, and shouted loudly, which drew attention

neighboring lodges. It was during intermission. Following Gogol, he entered our

Alexander Pavlovich Efremov lay down, and Konstantin whispered in his ear: “Do you know

who do we have? This is Gogol. "Efremov, bulging his eyes also with amazement and joy,

ran into an armchair and told the news to the late Stankevich and someone else from

our acquaintances. In one minute, several tubes and binoculars turned on our

I lay down, and the words "Gogol. Gogol" reverberated through the armchairs. I don't know if he noticed

this movement, only after saying a few words that he was again in Moscow for

a short time, Gogol left.

Despite the brevity of the meeting, we all noticed that in relation to us

Gogol became a completely different person, while there were no

reasons that, during his absence, could bring us closer. The very parish

him in the box already showed confidence that we would be delighted with him. We rejoiced and

surprised at this change. Subsequently, from conversations with Pogodin, I

concluded (I think the same now) that his stories about us, about our high

opinion about Gogol's talent, about our ardent love for his works