The theme of the homeland in the poem by A.T. Tvardovsky “Vasily Terkin. Reflection of the era in the works of A. Tvardovsky Organizational moment, motivation

The first poems of Alexander Trifonovich Tvardovsky were published in Smolensk newspapers in 1925-1926, but fame came to him later, in the mid-30s, when “The Country of Ant” (1934-1936) was written and published - a poem about the fate of a peasant - individual farmer, about his difficult and difficult path to the collective farm. The poet's original talent clearly manifested itself in it.

In his works of the 30-60s. he embodied the complex, turning-point events of the time, shifts and changes in the life of the country and the people, the depth of the national historical disaster and feat in one of the most brutal wars that humanity experienced, rightfully occupying one of the leading places in the literature of the 20th century.

Alexander Trifonovich Tvardovsky was born on June 21, 1910 in the “farm of the Stolpovo wasteland”, belonging to the village of Zagorye, Smolensk province, into a large large family of a peasant blacksmith. Note that later, in the 30s, the Tvardovsky family suffered a tragic fate: during collectivization they were dispossessed and exiled to the North.

From a very early age, the future poet imbibed love and respect for the land, for the hard work on it and for blacksmithing, the master of which was his father Trifon Gordeevich - a man of a very original, tough and tough character and at the same time literate, well-read, who knew by heart a lot of poems. The poet's mother, Maria Mitrofanovna, had a sensitive, impressionable soul.

As the poet later recalled in “Autobiography,” long winter evenings in their family were often devoted to reading aloud books by Pushkin and Gogol, Lermontov and Nekrasov, A.K. Tolstoy and Nikitin... It was then that a latent, irresistible craving for poetry arose in the boy’s soul, which was based on rural life itself, close to nature, as well as traits inherited from his parents.

In 1928, after a conflict and then a break with his father, Tvardovsky broke up with Zagorye and moved to Smolensk, where for a long time he could not get a job and survived on a pittance of literary earnings. Later, in 1932, he entered the Smolensk Pedagogical Institute and, while studying, traveled as a correspondent to collective farms, wrote articles and notes about changes in rural life for local newspapers. At this time, in addition to the prose story “The Diary of a Collective Farm Chairman,” he wrote the poems “The Path to Socialism” (1931) and “Introduction” (1933), in which colloquial, prosaic verse predominates, which the poet himself later called “riding with the reins lowered.” They did not become a poetic success, but played a role in the formation and rapid self-determination of his talent.

In 1936, Tvardovsky came to Moscow, entered the philological faculty of the Moscow Institute of History, Philosophy, Literature (MIFLI) and in 1939 graduated with honors. In the same year he was drafted into the army and in the winter of 1939/40 he participated in the war with Finland as a correspondent for a military newspaper.

From the first to last days During the Great Patriotic War, Tvardovsky was an active participant - a special correspondent for the front-line press. Together with active army Having started the war on the Southwestern Front, he walked along its roads from Moscow to Koenigsberg.

After the war, in addition to the main literary work, actually poetic creativity, for a number of years he was the editor-in-chief of the magazine “New World”, consistently defending in this post the principles of truly artistic realistic art. Heading this magazine, he contributed to the entry into literature of a number of talented writers - prose writers and poets: F. Abramov and G. Baklanov, A. Solzhenitsyn and Yu. Trifonov, A. Zhigulin and A. Prasolov, etc.

The formation and development of Tvardovsky as a poet dates back to the mid-20s. While working as a rural correspondent for Smolensk newspapers, where his notes on village life had been published since 1924, he also published his youthful, unpretentious and still imperfect poems there. In the poet’s “Autobiography” we read: “My first published poem “New Hut” appeared in the newspaper “Smolenskaya Village” in the summer of 1925. It started like this:

Smells like fresh pine resin

The yellowish walls shine.

We'll live well in the spring

Here in a new, Soviet way...”

With the appearance of “The Country of Ant” (1934-1936), which testified to the entry of its author into a period of poetic maturity, the name of Tvardovsky became widely known, and the poet himself asserted himself more and more confidently. At the same time, he wrote cycles of poems “Rural Chronicle” and “About Grandfather Danila”, poems “Mothers”, “Ivushka”, and a number of other notable works. It is around the “Country of Ant” that the emerging contradictory artistic world of Tvardovsky has been grouped since the late 20s. and before the start of the war.

Today we perceive the work of the poet of that time differently. One of the researchers’ remark about the poet’s works of the early 30s should be recognized as fair. (with certain reservations it could be extended to this entire decade): “The acute contradictions of the collectivization period in the poems, in fact, are not touched upon; the problems of the village of those years are only named, and they are solved in a superficially optimistic way.” However, it seems that this can hardly be attributed unconditionally to “The Country of Ant,” with its peculiar conventional design and construction, and folklore flavor, as well as to the best poems of the pre-war decade.

During the war years, Tvardovsky did everything that was required for the front, often spoke in the army and front-line press: “wrote essays, poems, feuilletons, slogans, leaflets, songs, articles, notes...”, but his main work during the war years was the creation lyric-epic poem “Vasily Terkin” (1941-1945).

This, as the poet himself called it, “A Book about a Soldier,” recreates a reliable picture of front-line reality, reveals the thoughts, feelings, and experiences of a person in war. At the same time, Tvardovsky wrote a cycle of poems “Front-line Chronicle” (1941-1945), and worked on a book of essays “Motherland and Foreign Land” (1942-1946).

At the same time, he wrote such lyrical masterpieces as “Two Lines” (1943), “War - there is no crueler word...” (1944), “In a field dug with streams...” (1945), which were first published after the war, in the January book of the magazine “Znamya” for 1946.

Even in the first year of the war, the lyrical poem “House by the Road” (1942-1946) was started and soon after its end. “Its theme,” as the poet noted, “is war, but from a different side than in “Terkin” - from the side of home, family, wife and children of a soldier who survived the war. The epigraph of this book could be lines taken from it:

Come on people, never

Let's not forget about this."

In the 50s Tvardovsky created the poem “Beyond the Distance - Distance” (1950-1960) - a kind of lyrical epic about modernity and history, about a turning point in the lives of millions of people. This is a detailed lyrical monologue of a contemporary, a poetic narrative about the difficult destinies of the homeland and people, about their complex historical path, about internal processes and changes in spiritual world person of the 20th century.

In parallel with “Beyond the Distance, the Distance,” the poet is working on a satirical poem-fairy tale “Terkin in the Other World” (1954-1963), depicting the “inertia, bureaucracy, formalism” of our life. According to the author, “the poem “Terkin in the Other World” is not a continuation of “Vasily Terkin”, but only refers to the image of the hero of “The Book about a Fighter” to solve special problems of the satirical and journalistic genre.”

IN last years life, Tvardovsky writes a lyrical poem-cycle “By the right of memory” (1966-1969) - a work of tragic sound. This is a social and lyrical-philosophical reflection on the painful paths of history, on the fate of an individual, on the dramatic fate of one’s family, father, mother, brothers. Being deeply personal and confessional, “By the Right of Memory” at the same time expresses the people’s point of view on the tragic phenomena of the past.

Along with major lyric-epic works in the 40s and 60s. Tvardovsky writes poems that poignantly echo the “cruel memory” of the war (“I was killed near Rzhev,” “On the day the war ended,” “To the son of a dead warrior,” etc.), as well as a number of lyrical poems that made up the book “ From the lyrics of these years” (1967). These are concentrated, sincere and original thoughts about nature, man, homeland, history, time, life and death, the poetic word.

Written back in the late 50s. and in his programmatic poem “The whole essence is in one single covenant...” (1958), the poet reflects on the main thing for himself in working on the word. It is about a purely personal beginning in creativity and about complete dedication in the search for a unique and individual artistic embodiment of the truth of life:

The whole point is in one single covenant:

What I will say before the time melts,

I know this better than anyone in the world -

Living and dead, only I know.

Say that word to anyone else

There's no way I could ever

Entrust. Even Leo Tolstoy -

It is forbidden. He won’t say - let him be his own god.

And I'm only mortal. I am responsible for my own,

During my lifetime I worry about one thing:

About what I know better than anyone in the world,

I want to say. And the way I want.

In the later poems of Tvardovsky, in his penetrating personal, in-depth psychological experiences of the 60s. first of all, the complex, dramatic paths of folk history are revealed, the harsh memory of the Great Patriotic War sounds, the difficult fate of the pre-war and post-war villages respond with pain, the events of folk life evoke a heartfelt echo, and the “eternal themes” of lyrics find a sorrowful, wise and enlightened solution.

Native nature never leaves the poet indifferent: he vigilantly notices, “as after the March snowstorms, / Fresh, transparent and light, / In April - they suddenly turned pink / Verb-like birch forests”, he hears “an indistinct conversation or hubbub / In the tops of centuries-old pines “(“ That sleepy noise was sweet to me ...”, 1964), the lark, heralding spring, reminds him of a distant childhood.

Often the poet builds his philosophical thoughts about the life of people and the change of generations, about their connection and blood relationship in such a way that they grow as a natural consequence of the image of natural phenomena (“Trees planted by grandfather ...”, 1965; “Lawn in the morning from under the typewriter ...”, 1966; “Birch”, 1966). In these verses, the fate and soul of a person are directly connected with the historical life of the motherland and nature, the memory of the fatherland: they reflect and refract the problems and conflicts of the era in their own way.

The theme and image of the mother occupy a special place in the poet’s work. So, already at the end of the 30s. in the poem “Mothers” (1937, first published in 1958), in a form of blank verse not quite usual for Tvardovsky, not only the memory of childhood and a deep filial feeling, but also a heightened poetic ear and vigilance, and most importantly, an ever more revealing and the growing lyrical talent of the poet. These verses are distinctly psychological, as if reflected in them - in the pictures of nature, in the signs of rural life and life inseparable from it - a maternal image so close to the poet's heart appears:

And the first noise of leaves is still incomplete,

And a green trail on the grainy dew,

And the lonely knock of the roller on the river,

And the sad smell of young hay,

And the echo of a late woman's song,

And just sky, blue sky -

They remind me of you every time.

And the feeling of filial grief sounds completely different, deeply tragic in the cycle “In Memory of a Mother” (1965), colored not only by the most acute experience of irretrievable personal loss, but also by the pain of nationwide suffering during the years of repression.

In the land where they were taken in droves,

Wherever there is a village nearby, let alone a city,

In the north, locked by the taiga,

All there was was cold and hunger.

But my mother certainly remembered

Let's talk a little about everything that has passed,

How she didn’t want to die there, -

The cemetery was very unpleasant.

Tvardovsky, as always in his lyrics, is extremely specific and precise, right down to the details. But here, in addition, the image itself is deeply psychologized, and literally everything is given in sensations and memories, one might say, through the eyes of the mother:

So-and-so, the dug earth is not in a row

Between centuries-old stumps and snags,

And at least somewhere far from housing,

And then there are the graves right behind the barracks.

And she used to see in her dreams

Not so much a house and a yard with everyone on the right,

And that hillock is in the native side

With crosses under curly birch trees.

Such beauty and grace

In the distance is a highway, road pollen smokes.

“I’ll wake up, I’ll wake up,” the mother said, “

And behind the wall is a taiga cemetery...

In the last of the poems of this cycle: “Where are you from, / Mother, did you save this song for old age?..” - a motif and image of “crossing” that is so characteristic of the poet’s work appears, which in “The Country of Ant” was represented as a movement towards the shore.” new life”, in “Vasily Terkin” - as the tragic reality of bloody battles with the enemy; in the poems “In Memory of a Mother,” he absorbs pain and sorrow about the fate of his mother, bitter resignation with the inevitable finitude of human life:

What has been lived is lived through,

And from whom what is the demand?

Yes, it's already nearby

And the last transfer.

Water carrier,

Gray old man

Take me to the other side

Side - home...

In the poet’s later lyrics, the theme of continuity of generations, memory and duty to those who died in the fight against fascism sounds with new, hard-won strength and depth, which enters with a piercing note in the poems “At night all the wounds hurt more painfully...” (1965), “I know no fault of mine...” (1966), “They lie there, deaf and dumb...” (1966).

I know it's not my fault

The fact that others did not come from the war,

The fact that they - some older, some younger -

We stayed there, and it’s not about the same thing,

That I could, but failed to save them, -

That's not what this is about, but still, still, still...

With their tragic understatement, these poems convey a stronger and deeper sense of involuntary personal guilt and responsibility for human lives cut short by the war. And this persistent pain of “cruel memory” and guilt, as one could see, applies to the poet not only to military victims and losses. At the same time, thoughts about man and time, imbued with faith in the omnipotence of human memory, turn into an affirmation of the life that a person carries and keeps within himself until the last moment.

In Tvardovsky's lyrics of the 60s. the essential qualities of his realistic style were revealed with special fullness and force: democracy, the inner capacity of the poetic word and image, rhythm and intonation, all poetic means, with external simplicity and uncomplicatedness. The poet himself saw the important advantages of this style, first of all, in the fact that it gives “reliable pictures of living life in all its imperious impressiveness.” At the same time, his later poems are characterized by psychological depth and philosophical richness.

Tvardovsky owns a number of thorough articles and speeches about poets and poetry containing mature and independent judgments about literature (“The Tale of Pushkin”, “About Bunin”, “The Poetry of Mikhail Isakovsky”, “On the Poetry of Marshak”), reviews and reviews about A. Blok, A. Akhmatova, M. Tsvetaeva, O. Mandelstam and others, included in the book “Articles and Notes on Literature”, which went through several editions.

Continuing the traditions of Russian classics - Pushkin and Nekrasov, Tyutchev and Bunin, various traditions of folk poetry, without bypassing the experience of prominent poets of the 20th century, Tvardovsky demonstrated the possibilities of realism in the poetry of our time. His influence on contemporary and subsequent poetic development is undeniable and fruitful.

Classes: 7 , 8

Presentation for the lesson

Back forward

Attention! The slide preview is for informational purposes only and may not represent the full extent of the presentation. If you are interested in this work, please download the full version.

Smolensk land. The Smolensk region is a region so generous with famous names. South of Smolensk is the small town of Pochinok (I visit it several times a year), and 12 km from it is the Zagorye farmstead - the place where A.T. was born more than 100 years ago. Tvardovsky.

Lesson objectives:

- Tell us about the homeland of A.T. Tvardovsky. Based on biographical facts, determine the themes of the poet’s poems.

- Develop the concept of a lyrical hero.

- Strengthen skills:

- compare poems by different authors;

- work with the textbook;

- read expressively, conveying the author’s ideas and feelings. - Activate the cognitive activity of students, stimulate and develop mental activity.

- To foster a sense of patriotism and pride in one’s small homeland.

Equipment: multimedia projector, screen, Microsoft PowerPoint presentation

During the classes

1. Organizational moment.

Announcing the topic and objectives of the lesson.

2. Updating knowledge.

Comparison as an analysis technique to identify common themes.

Name the poets and singers of your native nature and land known to you. (S. Yesenin, I. Bunin, A. Tolstoy)

What unites these poets and their works? (Love for the native land. Feeling of the connection between man and nature, expression of spiritual moods, human states through a description of nature.)

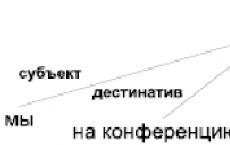

3. Explanation of new material.(Slide No. 1)

- Teacher's opening speech. The personality of the writer is known through his work, and the fundamental beginning of the personality is the attitude of a person to the places where he was born and raised. A.T. Tvardovsky carried his love for his native land, to his origins throughout his life, not forgetting about him either in the years of joy, or in the time of troubles and separations. The image of his small homeland is visibly present in many of his works. (Slide No. 2)

- Working with the textbook. Students reading excerpts from the poet’s “Autobiography”.

(up to the words “Since that time I have been writing ...” Literature. 7th grade. Textbook reader for general educational institutions. At 2 hours / author-compiler V.Ya. Korovin)

So, the poet was born on the farm Zagorye of the Pochinkovsky district of the Smolensk region on June 21 (8), 1910 in the family of a rural blacksmith, as you know, blacksmiths were always the most needed and respected people in the village. On the father's side, Tvardovsky's ancestors were farmers, blacksmiths, on the mother's side - military people, owned estates, went bankrupt, became single-palace dwellers. Zagorye and Pochinok, the Luchesa River, Borki - these names are the components of Tvardovsky's small homeland. The house in which the poet was born has not survived to this day. Years of repression and war wiped Zagorje off the face of the earth. (Slide No. 3) In the fall of 1943, Tvardovsky, along with units of the 32nd Cavalry Division, ended up near his native farm and was shocked by what he saw: “I didn’t even recognize the ashes of my father’s house. Not a tree, not a garden, not a brick or a post from a building—everything is covered with bad grass, tall as hemp, which usually grows on the ashes. I did not find at all a single sign of that piece of land, which, closing my eyes, I can imagine to the speck, with which all the best that is in me is connected. (But not everyone knows that the farm did not die during the war, but much earlier, when the Tvardovsky family was evicted from there.) [ 1 ]

The Zagorye Farm Museum opened on June 21, 1988. But first a huge amount of restoration work was done. The first memorial stone appeared on the Zagorye farm. Tvardovsky’s brothers, Ivan Trifonovich and Konstantin Trifonovich, and his sister Anna Trifonovna, (Slide No. 4) provided great assistance in the creation of the museum. The poet’s younger brother Ivan Trifonovich Tvardovsky, who then lived in the Krasnoyarsk Territory, made drawings of the farm and the interior of the house. And then he moved to his homeland, he made all the furniture for the exhibition himself, Ivan Trifonovich was the director and caretaker of the museum until the end of his days. (Ivan Trifonovich Tvardovsky passed away on June 19, 2003. He was buried in the village of Seltso, which is located a kilometer from the farm)

- Beginning of the correspondence tour of Zagorje. (Slide No. 5)

On the territory of the museum complex there is a house with an attached barnyard. There are no authentic items in the museum, since the poet’s family - parents, brothers, sisters - were repressed and deported to the Trans-Urals. Before you is the simple life of a family. On the wall there is a clock with a pendulum, a mirror in a carved frame. A stove and a wooden partition separate the bedroom, where there is an iron bed for parents and a bed for children. Opposite the door there is a large closet that divides the room into two parts. On the table, covered with a lace tablecloth, is a huge samovar. Nearby there is a hard wooden sofa and several Viennese chairs. There is a chest of drawers in the corner. He is wearing a foreign-made sewing machine. Homespun rugs are laid on the floor. In the other “red” corner of the room, under the “images of holy saints,” there is a corner table with a stack of books.

To the left is a hanger with painted towels. Items characterizing the period of the 1920-1930s were collected by researchers from the Smolensk Museum-Reserve during expeditions to the villages surrounding Zagorye in the Pochinkovsky district. (Slide No. 7)

(Slide No. 8) In the barnyard there is a stall for a cow and a horse, as in an ordinary peasant farm. It was possible to enter here through the cold entryway from the house, so as not to walk in the cold and snow in winter.

(Slide No. 9) In front of the house you can see a hay barn and a bathhouse in which the young village correspondent A.T. worked. – this is how Tvardovsky signed his first notes in the newspaper “Smolenskaya Derevnya”.

(Slide No. 10) Behind the house, a little further away, there is a blacksmith shop. It contains a forge with bellows, an anvil, and blacksmith's tools can be seen on the walls.

(Slide No. 11) A well, a young spruce forest, an apple orchard - these are also details of a former life:

- A trained student reads expressively from the textbook “Brothers” (1933).

(the footnote at the end of the poem is explained) The poet wrote about the bitter fate of the Tvardovsky family in his works, for example, in the poem “Brothers” (1933):

How are you brother?

Where are you, brother?

What are you doing, brother?

On which White Sea Canal?

This is about the elder brother Konstantin, and about all the brother people who, as enemies of the people, were herded to the construction of the White Sea Canal. All the hardships of life in the harsh taiga region fell on the fragile shoulders of Maria Mitrofanovna, because... the father was constantly away from the family, earning his daily bread.

4. Primary application of acquired knowledge.

Questions for the class:

1) So, with what events in the Tvardovsky family is the ending of the poem connected?

2) What do you know about the concept lyrical hero?

Help: A lyrical hero is the image of that hero in a lyrical work, whose experiences, thoughts and feelings are reflected in it. It is by no means identical to the image of the author, although it reflects his personal experiences associated with certain events in his life, with his attitude to nature, public life, people. Any personal experience of a poet only becomes a fact of art when it is an artistic expression of feelings and thoughts that are typical of many people. Lyrics are characterized by both generalization and fiction. [2]

It is known that the basis of a lyrical work is an artistic thought, given in the form of direct experience. But we must not forget that lyrical experiences are closely related to real life the one who creates this experience. [3]

3) What feelings does the lyrical hero experience when remembering his childhood?

5. Checking homework.

Students recite the poet’s poems by heart: “The snow has darkened blue...”, “July is the crown of summer...”, “We played along the smoky ravines...”, “At the bottom of my life...”, “On the day the war ended...”, “I I know it’s not my fault...” and etc.

- Activating students' thinking .

Questions for the class:

- What did the poet write about? What life values did he affirm through his creativity?

- Do you agree with the words of A.I. Solzhenitsyn, who noted “the Russian character, the peasantry, the earthiness, the inaudible nobility of Tvardovsky’s best poems”?

- What are the main themes of his poems?

- What questions torment the front-line poet?

Conclusion: Landscape lyrics Tvardovsky is distinguished by its philosophy and visual power (“July is the top of summer”). The world of childhood and youth in the Zagorye farm sounds in many of the poet’s works: from the first to the last - in the poem “By the Right of Memory.” The theme of the “Small Motherland”, the line of “memory” becomes the main one in the poet’s work. Turning to the past, to memory allows you to comprehend the highest moments of existence. Memory feeds the poet’s lyricism and restores what was true happiness and joy.

- Continuation of the correspondence excursion.

As you know, all children grow up and sooner or later leave their home. This is what happened with Tvardovsky: his beloved region was a remote place that did not provide the opportunity to develop his talent, in which the poet himself was very confident. But Trifon Gordeevich’s attitude towards his son’s passion for literature was complex and contradictory: he was either proud of him, or doubted the well-being of his future fate if he took up literary work. The father preferred reliable peasant work to the “fun” of writing, a hobby that he believed his son should develop. Let us turn to the “Autobiography” of the poet.

- Working with the textbook. Students read an excerpt from Autobiography. (Since 1924...the cause of significant changes in my life") (Slide No. 12)

At the eighteenth year of his life, Alexander Trifonovich Tvardovsky left his native Zagorje. By this time, he had already been to Smolensk more than once, once visited Moscow, personally met M.V. Isakovsky, and became the author of several dozen published poems. The big world beckoned to him. But the separation was not easy. After moving to Moscow, A. T. Tvardovsky most keenly felt the connection with his small homeland. (Slide No. 13) And the classic unforgettable lines were born:

I'm happy.

I'm glad

With the thought of living with your beloved,

What's in my native country

There is my native land.

And I'm still pleased -

Let the reason be funny -

What in the world is mine

Pochinok station.

Pochinok station (1936).

(Slide No. 15) There is another memorable place in the city of Pochinok. On the central square of the city, next to the House of Culture, on June 21, 2010, on the 100th anniversary of the poet’s birth, a bust of A. T. Tvardovsky, authored by sculptor Andrei Kovalchuk, was inaugurated.

Residents of the Smolensk region are proud of their famous countryman and sacredly cherish everything connected with his name. After all, the most precious thing that every person has is the place where he was born, his small homeland, and it is always in his heart.

In the poem Vasily Terkin (chapter “About myself”) Tvardovsky wrote:

I left home once

The road called into the distance.

The loss was no small

But the sadness was light.And for years with tender sadness -

Between any other worries -

Father's corner, my old world

I have a shore in my soul.

7. Reflection and summing up the lesson

Questions for the class: What new did we learn today? Could you now distinguish Tvardovsky's poems from the poems of other poets? Has your perception of previously learned poems changed? Which tasks did you like best?

Conclusion:

Without a doubt, the Smolensk region was a moral and aesthetic support in the work of A.T. Tvardovsky. She nourished with her life-giving juices the enormous talent of the great Russian poet, who deeply reflected in his best poems and poems.

Making marks.

Homework: read the memoirs about Tvardovsky in the textbook, use them when preparing a story about the poet.

Bibliography:

- Farm "Zagorye" - museum-estate of A.T. Tvardovsky http://kultura.admin-smolensk.ru/476/museums/sagorie/ ;

- Literature: Reference. Materials: Book. for students / L64 S.V. Turaev, L.I. Timofeev, K.D. Vishnevsky and others - M.: Education, 1989. P.80 - 81.;

- Skvoznikov V.D. Lyrics // Theory of Literature: Fundamentals. problem in history lighting – M., 1964. – Book 2: Types and genres of literature. – P.175.;

- Romanova R.M. Alexander Tvardovsky: Pages of life and creativity: Book. for students Art. classes cf. school – M.: Education, 1989. – 60 p.;

- Tvardovsky A.T. Poems. Poems. – M.: Artist. lit., 1984. – 559 p. (Classics and contemporaries. Poetic book);

- “Small Motherland” in the poetry of A. T. Tvardovsky: reading the lyrical lines... http://www.rodichenkov.ru/biblioteka/;

- In the homeland of Tvardovsky http://lit.1september.ru/article.php?ID=200401210;

- The museum-estate of A.T. Tvardovsky is 15 years old http://www.museum.ru/N13689.

PART SEVEN

In the article “On the big and small homeland” (1958), Alexander Tvardovsky wrote that “... the feeling of homeland in the broad sense - the native country, the fatherland - is complemented by the feeling of the small, original homeland, the homeland in the sense of native places, fatherland , district, city or village. This small homeland, with its special appearance, with its, albeit most modest and unassuming, beauty appears to a person in childhood, at the time of lifelong impressions of the childish soul, and with it, this separate and personal homeland, he comes over the years to that a big homeland that embraces all the small ones and - in its great whole - is one for everyone.”

Small Motherland, as the poet calls his native place, “...for every artist, especially an artist of words, a writer..., is of great importance.”

This is about a small homeland in general. And here are the lines of Alexander Tvardovsky from the essay “On the Native Ashes” (1943) about his personal small homeland, narrowed down to his native village of Zagorye, destroyed by evil forces in the first years of collectivization: “I did not find at all a single sign of that piece of land that, Closing my eyes, I can imagine myself, every speck, and with which all the best that is in me is connected. Moreover, this is me as a person. This connection has always been dear to me and even painful.”

These words are infinitely dear and sweet to me, because I feel the same way and in the same way, closing my eyes, I could always imagine “every single spot” that surrounded us in childhood. And I’m glad that my brother did not forget to say this in his work.

Our native Zagoryevo farm ceased to exist in 1931, when I was sixteen. The family was taken to a disastrous special settlement in the Trans-Urals, on the taiga river Lyalya. The return to their native places never happened. The difficult circumstances of those years scattered the entire family in all directions. But in our souls, without exaggerating, I can say that we all carefully preserved the memory of our small homeland. And wherever we happened to live and work, we listened with trepidation and read every new stanza of Alexander Trifonovich, where our native places were mentioned, savored and memorized the poems “On the Zagorye Farm”, “A Trip to Zagorye”, “For a Thousand Miles” , “Brothers” - in a word, every line with episodes from the shepherd time of our childhood, which excited and tenderly touched our feelings.

- 312 -Years and decades passed, but there was still no opportunity to set foot on the fatherly land, “... where the mystery of native speech was introduced in one’s own way.” The same reason held me back: since almost my entire life had passed under the sign of “social inferiority,” it was not a good idea to go there.

But in the spring of 1977, I received a letter from a senior researcher at the Smolensk Regional Museum-Reserve, Raisa Moiseevna Minkina. She asked me to think and try to make something for the exhibition dedicated to A.T. Tvardovsky, since she knew that I was a woodcarver by profession and knew intarsia work. By that time, one of my crafts was in the museum of the Smolensk Pedagogical Institute. “Should we offer a model of our former Zagoryevo estate?” - I thought. And again I remembered Alexander Trifonovich’s lines about his native places: “And over the years, with tender sadness, Between any other anxieties, my father’s corner, my former world, I cherished in my soul.” And again: “And the noises of the forest, and the conversations of birds, And the simple appearance of poor nature, I cherish everything in my memory, without losing it A thousand miles from my native land.”

Having thought through and weighed everything, I sent a letter to the Smolensk Museum, proposing a model of the Zagoryevo estate on a scale of one to fifty for A. T. Tvardovsky’s exhibition. The response from Smolensk came immediately: “We accept the offer, we wish you success.”

From June to mid-October I was busy with this work. The model was made, packaged and sent by luggage at passenger speed from Abakan. All this happened in the Ermakovsky district of the Krasnoyarsk Territory, where I lived in the village of Tanzybey. The nearest railway station, Abakan, where I could drop off my parcel as luggage, is 150 kilometers away. How to get there with such a burden? But as a sign of memory of Alexander Trifonovich - the author of “Vasily Terkin” - the soldiers of the local unit, stationed in those years on the outskirts of Tanzybey, helped me. Unfortunately, I can no longer name the name of the political instructor who reacted so understandingly to my request. In general, the parcel was sent, and, to my surprise, without payment: baggage shipments to government organizations were made free of charge. And in the last days of October, I flew from Abakan to Moscow, from there I took a train to Smolensk and immediately found out that the parcel was already in the luggage compartment. It was just according to my calculations: I rushed on this road in order to personally be present at the opening of the package and find out what the first impression of my work would be among the museum staff. Thank God, everything turned out well: the parcel arrived without damage, I was greeted warmly at the museum. I was very glad that everyone liked the exhibit and a place for its exhibition was determined.

Could I have foreseen then that the model would become the basis for the restoration of our Zagorye farm? I did not rule out such a possibility. “My father’s corner, my former world, I cherish the shore in my soul” - lines from “Terkin” (chapter “About Myself”). These words of the poet could not but evoke the desire of everyone who holds the name of Alexander Trifonov dear.

- 313 -cha, in order to somehow imagine, and even better, visually survey what this world of all his beginnings, so dear to the poet’s heart, was like. This was the feeling that made me take up the model of the estate.

The model became almost an event for Smolensk residents, and the press did not pass over it in silence. The regional newspaper “Rabochy Put” on November 1, 1977 published information under the heading “Gift to the Museum”, where there were the following words: “The model of the Zagorye farm - the birthplace of the outstanding Soviet poet Alexander Trifonovich Tvardovsky - was made by his brother Ivan Trifonovich and donated to the Smolensk Regional Museum " On December 22, 1977, the same newspaper published an essay by N. Polyakov “By the Hand of a True Master.” It tells about everything that prompted the poet’s brother to take on this work, by what means and with what care it was completed.

Before returning to Siberia, I invited a photojournalist from “Working Path” to photograph the model already on display. I received the photographs while already in Tanzybey. Great shots. I sent them to A.I. Kondratovich, Yu.G. Burtin, V.V. Dementyev, P.S. Vykhodtsev and some other researchers of my brother’s work, believing that it would be interesting for them. I was not mistaken - they all responded with heartfelt letters, approved of my work, and thanked me. Maybe then the pain pierced my heart: after all, there is nothing like this. Instead of a farm, there is a field. And it turns out that I wasn’t the only one who experienced this feeling. Soon the photo appeared in print. And on the pages of Literary Russia on March 31, 1978, an essay by V.V. Dementyev “A Trip to Zagorye” was published. In it I read: “Ivan Trifonovich did a great thing, but it seems to me that while there is time, before the wide Russian field is overgrown with wolf small forests, while the poet’s relatives and friends are still alive, we are obliged, we must, we are called upon to restore the Zagorye farm both for themselves and for future generations who will blaze unovergrown paths here.”

I must add that V.V. Dementyev, having received a photograph of the model from me, left all his affairs in Moscow and went to the Smolensk region to again and again touch his soul with “The Poet’s Field,” as he called one of the chapters of his book on Russian poetry "Confessions of the Earth". Together with the Smolensk poet Yuri Pashkov, they reached the fields of Zagoryevo and then met the living contemporaries of Alexander Trifonovich in his small homeland.

The essay by V.V. Dementyev “A Trip to Zagorye” became Starting point on the issue of recreating the Zagorye farm as a memorial to A.T. Tvardovsky. Over the course of a whole decade, this issue in one form or another surfaced again and again on the pages of central and peripheral newspapers, almanacs and magazines. Dementiev’s call was supported by “Red Star” with publications by V. Lukashevich, and “Rural Life” with essays by V. Smirnov, and “Izvestia” with essays by Albert Plutnik “On the Old Smolensk Road”.

On September 1, 1986, the Smolensk Regional Executive Committee finally made a decision “On the revival of the Tvardovsky estate on the Zagorye farm.”

- 314 -Director of the Smolensk Regional Museum Alexander Pavlovich Yakushev wrote to me:

“Dear Ivan Trifonovich! The Directorate of the Smolensk Regional Museum-Reserve invites you to come to the city of Smolensk to carry out work on making furniture that was in the house of Trifon Gordeevich Tvardovsky. We are ready to appoint you to one of the full-time positions of a museum worker, provide you with a place to work and relevant materials. Please, upon receipt of this letter, respond to us, informing us of your consent and time of arrival.”

I immediately replied that I was ready to come and make everything that was furnished in our house when our brother Alexander left Zagorye.

“Dear Ivan Trifonovich! We received your letter from 250586 - thank you very much for agreeing to come to Smolensk in the 2nd half of July. I understand the difficulties, as well as the fact that, in theory, no one needs to agitate for the creation of a museum dedicated to A. T. Tvardovsky in his homeland, i.e. it should have been done long ago work».

“I would ask you to estimate what we should prepare for the arrival from the instrument (you cannot bring everything with you), what specific material, etc., down to the smallest detail. Will there be any difficulties with housing in Smolensk?”

I arrived in Smolensk from Tanzybey on Sunday and spent the night with my sister in Zapolny. The meeting with Yakushev took place on July 20, and the impression from this meeting was good.

It seems that all authorities agree and are ready to help in organizing the museum,” Alexander Pavlovich informed me, “but the decision remains hanging in the air. As if someone is afraid of something: “Whatever happens!”

Alexander Pavlovich, at his own risk and fear, decided to take on the preparation of the museum, to produce everything that should represent the interior of the hut, as it was under the young Alexander Trifonovich.

So I invited you, Ivan Trifonovich,” continued Alexander Pavlovich, “remembering your opinion on this matter that, I agree, we will not be able to find anywhere exactly the corresponding analogues of the situation: there was a war here, there were Germans... And what is "analogues"? This does not always correspond exactly exactly. So, judging by the layout of the estate you made, I am convinced that you will be able to complete this task in the best possible way.

In correspondence with the staff of the Smolensk Museum, I also did not support the proposal to look for pieces of furniture in the villages of the Smolensk region similar to those that were in my father’s family in the late twenties. I was absolutely convinced that the most the best solution It will be if they allow me to make the furniture myself, based on the fact that I remember well what it was like. Moreover, such a task is within my reach due to my profession itself. And no one else can do this, first of all, because they don’t know what she was like. I was glad that the museum’s management approached me with such an offer, and I arrived in Smolensk with my own instrument.

Finding the most suitable location was not an easy task.

- 315 -for work. I did not agree to huddle in the cramped space of some basement city building, but they could not offer me anything else. It also turned out that the necessary material was not yet available: it was not possible to start work. The way out of this situation, in my opinion, could be to, without wasting time, go to the Pochinkovsky state farm, that is, directly to the homeland of Alexander Trifonovich, where, by the way, they fervently honor the memory of their fellow countryman-poet and annually solemnly celebrate the day his birth, and there to resolve the issues that arose: place of work, housing.

I arrived in Pochinok. My hometown turned out to be unrecognizable and unfamiliar to me. The last time I was in this trading place closest to Zagorye was with our father Trifon Gordeevich more than half a century ago. Every Sunday then numerous peasants gathered in Pochinok on their carts to the market to sell or buy something, but, perhaps, to sell more. My God, how many of those simple peasant carts used to gather here, how many things were on sale, what was not there! All kinds of living creatures: cows, piglets, calves, poultry, a variety of natural peasant products - butter, a variety of meat, honey, apples, eggs. There were so many different handicrafts: barrels, various tubs, gangs, troughs, spinning wheels, pottery, sieves, butter churns - well, in a word, all sorts of goodness: “Buy it - I don’t want it!” It smelled of tar, honey, horses and manure, and gingerbread too. And one could see and hear how purchases and sales took place with loud exchanges of opinions between those bargaining. For example, near some living creature, each side convinces, almost crossing itself and swearing in the name of the Lord, that it speaks only the truth, when the other still remains in doubt. There comes a moment when the parties make a gesture, the so-called “hands-on” - the deal is completed, and feelings peacefully transform into a state of goodwill towards each other.

The picture of old childhood impressions flashed by itself, as it were, when I, essentially for the first time, saw Pochinok of these days, so to speak - updated, greatly changed in all respects, ennobled with asphalt, with multi-storey buildings, with cars scurrying along the streets and with a complete absence of peasant carts, former bazaars and those simple private trading shops that were here at every step. It seems to be both good and beautiful. But, to be honest, I didn’t want to see the cold stone emptiness of the current shops that replaced the abundance of peasant bazaars. But this comes from different concepts and judgments about ours today.

Somehow the idea arose of visiting the district party committee before continuing on to the Pochinkovsky state farm. Here we reasoned with Alexander Pavlovich: tell the first secretary about everything that is to be started, about all the difficulties. There was hope that he could easily call the director of the state farm, and his word would be more effective than our request on behalf of the director of the regional museum. It turned out that way - we were lucky. The first one was

- 316 -at his place and received us very warmly. Introduced himself: - Nikolai Vasilievich. When I learned that I had come from Siberia and that my task was to make everything that was in the family of the father of the poet Alexander Tvardovsky for the period when he left his father’s family forever, the secretary stood up from the table and firmly shook my hand:

So this is a gift to all of us who can imagine the importance of the matter that we are thinking about here. Thank you, Ivan Trifonovich, for coming, for still being able to do the main thing, which is dear and sweet. Just think, my own brother came to his homeland to perpetuate the memory of our outstanding fellow countryman Alexander Trifonovich!

He immediately contacted the director of the Pochinkovsky state farm, Pyotr Vladimirovich Shatyrkin, by telephone, and one could easily understand that at the other end of the line they expressed gratitude and were ready to do everything so that work could begin without delay.

From Pochinok our path lay to Seltso - a state farm estate, from which only seven hundred meters away is the place where my father’s estate was, which was taken from us in 1931.

At parting, Nikolai Vasilyevich handed me a portrait of Alexander Trifonovich on a tree and souvenir towels made from Smolensk flax produced by the Smolensk Flax Mill with unique embossing.

From Pochinok to Selts it’s eighteen kilometers. My first trip there took place in 1980 for the 70th birthday of Alexander Trifonovich. I was kindly invited to these celebrations from Siberia to Moscow, from there, already as part of a group of Moscow writers, I arrived in Smolensk on the evening of June 19.

On June 20, they were received by the first secretary of the Smolensk regional party committee, then attended a ceremonial meeting of the Smolensk public, visited the historical museum, where an exhibition dedicated to Alexander Tvardovsky was displayed, visited the Smolensk Pedagogical Institute and got acquainted with the exhibition dedicated to the poet’s student years.

On June 21, we were taken from Smolensk directly to the poet’s homeland, where many Smolensk residents and guests had already gathered, eternally honoring the memory of Alexander Trifonovich. That day I was unable to find privacy, look around, or escape from the embrace of my solemnly excited fellow countrymen. I was deeply touched by their warmth and attention. I met those with whom I went to school in Lyakhovo. Now they saw a white-haired old pensioner, and there was no escape - the fellow countrymen could not hold back a tear, and it was to me, I don’t know how to say it, perhaps it’s painful to the point of tears.

I tried to find out the place where our house was, but even with the help of fellow countrymen it was hard to imagine that they showed me exactly that place. I admit, I was quite upset. By someone's indifferent will and indifference, the road from Pochinok to the Pochinkovsky state farm was laid exactly at the place of our former estate - no sign of everything that was. And really, it’s strange: there is

- 317 -photograph of 1943, which depicts the stay of Alexander Trifonovich with our father at the site of the former estate, where Trifon Gordeevich, kneeling down, peers into his native land next to our lake. Alexander Trifonovich stands there, deep in thought. This means that in 1943 there was still a sign, a trace of life in Zagorye. Then a bulldozer buried it all under the road surface. The dumping was carried out by moving the soil from the sides, and there was no trace left of the former hillock where the estate was.

As Alexander Trifonovich’s peer at the Lyakhov school, Akulina Ivanovna Bogomazova, told me, in those years when the road to the Pochinkovsky state farm was being built, the poet himself was here and donated part of the money from the State Prize for the poem “Beyond the Distance” for the construction of the House of Culture in Seltsa. He, of course, could not help but notice that the very site of the Zagoryev estate was already buried under the road. Apparently, out of modesty, he did not consider it tactful to say anything against, he remained silent - the deed had already been done and, it seems, he considered it unworthy to express displeasure with what had happened - he waved his hand. But he tried to provide the state farm with at least some assistance from his fellow countrymen. At his personal expense, a dug lake with an island was built, which is connected with the memory of his childhood years: on the estate in Zagorye there was also a lake with an island, as our father wanted. In addition, my brother donated several hundred volumes of books to the state farm library. Unfortunately, little has survived from them to this day - there was complete irresponsibility, and the books were stolen. Yes, you can regret it, but you can’t blame everyone - in society there is always a certain number of people for whom nothing is sacred.

The memory of Alexander Trifonovich is very carefully preserved at the Seltsov eight-year school. Sergei Stepanovich Selifonov, a native of these places, worked as its director for many years. After graduating from the pedagogical institute, he settled here in his native place. Back in the mid-sixties, he organized a school museum dedicated to the works of Alexander Tvardovsky. Nowadays, a large amount of documentary material has been accumulated in the form of letters from the poet in originals, many magazine and newspaper articles about him, books with autographs and dedicatory inscriptions from authors exploring the poet’s work: A. V. Makedonov, A. I. Kondratovich, P. S. Vykhodtsev, V. Ya. Lakshin and many others. There are many recollections of contemporaries about Alexander Trifonovich, there are also rare photographs of his meetings with his fellow countrymen, as well as the work of the famous wartime photojournalist Vasily Ivanovich Arkashev. All this cannot but evoke the deepest respect for S.S. Selifonov.

And let the reader forgive me, an old man, that my story turns out to be somewhat chaotic. Let us return to the moment of my arrival in Seltso together with the director of the regional museum. The director of the state farm, P.V. Shatyrkin, showed impeccable attentiveness to us.

“To organize a workshop,” he said, “I am placing at your disposal an apartment in two-story house, I authorize according to your

- 318 -discretion to select any of the available materials, I will assign a person to help you who will help you what to look for, where to look, how to get it, give you a ride, and so on.

"Wow!" - flashed through my thoughts. What more could you want? All that remained was to find out whether there was any hostel where I could get a place to stay for the night, but the director had already gotten ahead of me here, saying:

Don’t worry about housing, my apartment allows you to be accommodated at the proper level, rest assured.

Of course, I understood that benevolence does not come from nothing: here, in the poet’s homeland, his spirit hovers, gratitude and love for him lives.

Alexander Pavlovich Yakushev, who accompanied me that day from Smolensk to the state farm, witnessed my meeting with people in my native land. He was pleased that here for a long time they had been doing everything in their power to revive the farm where their famous fellow countryman was born and spent his childhood and youth, that this was, as it were, the very historical pride of the land of Smolensk, sung with a sense of filial duty by Alexander Tvardovsky.

I left home once

The road called into the distance

The loss was no small

But the sadness was bright

And for years with tender sadness -

Between any other alarms -

Father's corner, my old world

I have a shore in my soul

In these lines it is clearly recognized that “... the feeling of homeland in the broad sense of the native country, the fatherland, is complemented by the feeling of a small homeland...” This is what obligated us to recreate the Zagorye farm. And I don’t know another person in the Smolensk region who would put as much effort and effort as the former director of the Smolensk Regional Museum Yakushev, petitioning the regional authorities and seeking a solution to the issue of reviving the poet’s native farm.

Without waiting for official permission from the Smolensk Regional Executive Committee, under the personal responsibility of the director of the regional museum, I had to revive the Zagorye farm with a specific task - to make objects of ancient life in my father’s family. On that day, July 20, 1986, I stayed at the Pochinkovsky state farm, settling in the director’s apartment, where everything was provided at my service at the hotel level.

I started work literally the next day. And problems immediately arose. It’s not so easy to start doing something about carpentry where there is neither a workbench nor necessary materials. In this livestock farm, no purely carpentry work was carried out, therefore there was no carpentry workshop. Only the sawmill was working, and there was only one planing machine there, brought to complete disarray. There was no dryer, and there was no dry material suitable for making furniture on the farm.

- 319 -found. No craftsman can do anything from a board that has just come off the sawmill, and waiting for this board to dry under a canopy or in the sun, as I was told, was funny to hear.

I needed to look for some way out and, of course, talk to the director of the state farm, maybe he would contact neighboring farms and borrow or otherwise a couple of cubic meters of dry material. The necessary efforts were made in this direction, but all in vain.

And then I went to Smolensk to visit furniture factories with the director of the museum, where there must certainly be a supply of dry lumber. And it cannot help but happen that we will not meet understanding there - there was hope that our request would not be denied.

A.P. Yakushev dialed the phone number of some enterprise. Calling, as one could understand, a person he knew by his patronymic, he told him about our difficulties.

So, you can get it today? - asked Alexander Pavlovich. - Well, that’s great! Thank you!

We still failed to receive the material on the same day: it was still in the drying chamber, and we had to wait another two days.

I will never forget the guilty face of the state farm director:

Well, thank you, Ivan Trifonovich, for finding a way out. I worried within myself that I had not been able to resolve everything that was my responsibility on the spot, but... - he blamed himself, - don’t judge...

No, Pyotr Vladimirovich helped as much as he could. Well, firstly, he immediately assigned to me his most experienced worker, Pavel Filippovich Romanov, who is skilled in carpentry, and accustomed to work, and, moreover, is also an admirer of Alexander Trifonovich’s work. All this was very expensive for me. And our work with him went smoothly, as well as possible.

For the first time, the director of the local school, Sergei Stepanovich, allowed the use of workbenches from the school workshop; the chairman of the village council, Alexander Kharitonovich, who was well known to Alexander Trifonovich as a satirical poet, contributed to the preparation of alder wood for some special works. Worker Pavel Filippovich agreed to bring his own circular saw and planing machine, on which material of the required cross-section can be prepared. State farm electricians connected our equipment to the power grid. And a workshop was organized in a vacant state farm apartment, which made it possible to carry out all the upcoming work.

I had to make seemingly simple carpentry products that would be a copy of those that were in our family in the late twenties. These products were intended for the future memorial museum “Khutor Zagorye”. Was this difficult for me to do? Yes, this was far from an easy task, although I am a furniture maker by profession.

Of course, I remember everything well, down to the smallest detail.

- 320 -constructive elements of the home furnishings: tables, wardrobe, hard sofa, chest of drawers, chairs, hangers, shelves. It is clear that the furniture in our house was not from a factory in accordance with GOST, but was made God knows when to order by the hands of rural artisans, and therefore it was unique in its own way. And, before starting production, I prepared drawings from memory and calculated the sizes of the elements of each product. Factory-made materials such as plywood, board, plastic were not used in those years - everything was made from solid wood, that is, from natural pure wood, processed mainly by hand carpentry: sawn, planed, glued, finished. But I myself am from those places and years, and from the same family, and therefore I was convinced that I could cope with the task. Besides everything that was my duty and my obligation to the memory of my brother: if not me, then who can do it?

Pavel Filippovich and I had not yet managed to do anything, but the regional newspaper “Selskaya Nov” had already given information about the revival of the Zagorye farm with my participation, fellow countrymen began to appear alone and in groups to see with their own eyes that it was really so, that I was in Selts . Such visits were purely welcoming: people wanted to get to know me, congratulate me on my arrival, wish me success in my work, and express their approval for the very beginning. Photojournalists came, which sometimes embarrassed me very much - there was no need for an old person to expose himself to the lens - “old age is not joy.” Moreover, it distracted from the work and created interference. Rumors continued to expand, and soon notes appeared, and then essays about the beginning of the revival of the Zagorye farm, not only in the regional newspaper “Rabochy Put”, but also in the central newspapers: “Truda”, “Rural Life”, “Krasnaya Zvezda”, “ Izvestia".

Long before my arrival in my native place in the Smolensk region, I received a letter from an engineer at the Smolensk Research and Production Restoration Workshop in the Krasnoyarsk Territory (I think in 1982 or 1983). It reported that the named workshop was preparing technical documentation for the restoration of the estate in Zagorye, and therefore asked for answers to a number of questions. If possible, I answered all those questions that went beyond the data shown by me on the model of the estate, which was already in the Smolensk Museum, and recommended taking the model as a basis. Ultimately, the workshop did just that. I mention this letter only in order to show that for years the public had been nurturing the dream of the revival of Zagorje, promoting this issue as best they could, believing that the executive committee of the regional council would make a positive decision and Zagorje would be revived. For this purpose, technical documentation was prepared in advance.

By the end of August 1986, the workshop already had a wardrobe, a sofa, and tables. True, they were still in white form, not yet subjected to imitation and coating, but there was already something to look at. It was in those days that Izvestia special correspondent Albert Plutnik came to us. I looked with surprise at what was done and what else was in the preparations, I warmly regretted

- 321 -our hands. Finally, the long-awaited “go-ahead” from the executive committee of the regional council dated September 1, 1986 came to Seltso. This is where we really perked up.

In the essay “So it was on earth” (Izvestia, October 26, 1986), Albert Plutnik spoke about his visit to the temporary workshop where furniture was made for the museum in Zagorye:

“The Smolensk road leads us to a small settlement, which, as if afraid of exaggeration, was ashamed to call itself a village, called Selts, to a house where two elderly people, in leisurely conversations, make museum rarities. The fruits of their labor are right there, in a little room littered with sawdust and shavings: ordinary simple tables, a wardrobe, a sofa, chairs. But how rare is it if they are common? You can’t buy these anywhere, they are made “to order” - for one hut, in exact accordance with its size, number of eaters, and so on. By the way, the furniture is not original. Miraculously, from memory, we managed to restore a copy. This, in fact, as well as the purpose of the setting, is the uniqueness of the work in which state farm carpenter Pavel Filippovich Romanov and cabinetmaker Ivan Trifonovich Tvardovsky are engaged. He is older, in his seventies. It was he, Ivan Tvardovsky, who remembered the furniture of his father’s house, which stood on the Zagorye farm, which was near Selts, where he himself grew up, where his sisters and brothers grew up, including his brother Alexander, who left him in his youth... Things are moving quickly, although no one rushes the masters, except maybe years. The end of the work is already visible, and the excitement is growing stronger: the furniture won’t wander into strange corners. But I don’t have my own. There is no farm, no house - it has not been restored, although fifteen years have passed since the poet died.”

After a trip to Seltso, A. Plutnik had a meeting with the Deputy Chairman of the Smolensk Regional Executive Committee A.I. Makarenkov, after which the following lines appeared in the essay: “Today we can already say:

Zagorje will be reborn. The Executive Committee of the Smolensk Regional Council of People's Deputies adopted a special decision on this matter on September 1.”

In Seltsa, this news was greeted with enthusiasm by everyone. In the near future, the arrival of the regional authorities was expected, a meeting was expected to be held at which specific tasks would be discussed on the inclusion of contractors for construction work on Zagorye land.

It was planned to complete everything in ten months construction works to recreate the farm, but this turned out to be unrealistic. Many works were not taken into account in the project itself. So, before laying the foundations, it was necessary to recreate the previous topography of the estate. The relief, as I said, was greatly disturbed during the construction of the road to the state farm. Before the onset of cold weather, the restoration office barely had time to lay out the foundations. The blocks, however, were delivered, but they did not have time to lay them and level them - they could only be completed in the spring, on warm days, already in 1987.

I came to my small homeland with the thought that I would stay here for a while. a short time, maybe two months or a little more -

- 322 -I’ll make furniture for the museum, that’s the end of it - I’m returning to Siberia, where my family and my home are. It was still impossible to say whether we would live to see the day when the reconstruction of our native lands would begin. But fate decreed something cool. Before I had time to finish with the furniture, here’s the thing: not only has the decision been made, but the opening date for the museum has also been set. The return to Siberia was postponed. And then this thought appeared - should I move to my homeland?

It became clear that my presence here was necessary, since it was impossible to restore the damaged terrain without knowing what it was before, and I had to take responsibility for carrying out this work and constantly monitor the construction site. Yes, it cannot be otherwise if we want to recreate the farm as it was during the life of the young poet. This means: from start to finish I had to be here, since it all began from the moment I handed over the model to the Smolensk Museum, on the basis of which the technical documentation was prepared. But the layout gives only an external idea of the farm. The internal structure of any building is not shown on the model, which means that the presence of a person who must know everything down to the smallest details is mandatory. This applies to the hut, the barnyard, the bathhouse, and the forge. Their interior needs to be shown in real life.

Both the circumstances and the heightened feeling for my native place prompted me to explain to the administration that the idea of moving to Seltso had matured. My arguments were carefully accepted and supported. The state farm gave me an apartment, and the directorate of the regional museum issued a travel certificate to Siberia.

Not even a day had passed since I was in Abakan, waiting at the bus station for a bus that would take the familiar route along the Tuva highway to the village of Tanzybey, where I had lived for twenty years, a lot of work had been expended. And some kind of poignant feeling stirred my soul: I had to say goodbye to this place, which, in its own way, had already become close, lived with love, and therefore, everything that was coming, for the sake of which I made this trip, could not but cause sad thoughts.

I doubted whether my wife Maria Vasilievna would support my decision to move to the Smolensk region, since she is a native Siberian. But she was ready to go with me, as always, “even to the ends of the world.”

Our fees and efforts to sell the house, order containers for sending property, loading it, purchasing plane tickets and everything else related to relocation (removal from registration, transfer of pension documents, savings deposits, subscription publications) were completed in ten days.

On October 22, 1986, we were met by relatives in Smolensk. The next day we reached Selts.

The log houses for all Zagorye buildings were made by the Velizh Timber Industry Enterprise of the Smolensk Region in its production yard with the expectation that in the spring they would be transported disassembled to Zagorye and assembled by the timber industry enterprise itself on site with the installation of window frames

- 323 -and door blocks, arrangement of rafters, sheathing and hanging of doors and gates on hinges. All this work was completed by May 20, 1987.

Following the carpenters, the restorers hastened to temporarily cover the roofs of all buildings with roofing felt on a boardwalk so that, without fear of possible rains, they could carry out internal work - laying floors, fitting ceilings into the matrix, installing partitions, floors, and laying a Russian stove. The forge was covered, as agreed, with a fillet - planed plank in two layers. They, the restorers, hemmed the cornices, decorated the openings of windows and doors with platbands, screwed in handles, latches, and valves, and also laid the stove in the bathhouse and its arrangement. Their contract included erecting surrounding fences and partitions in the barnyard.

What is our farm like? It stands on a hillock right next to the road. An ordinary farm, that is, a separate piece of land, acquired by the father in the nineties of the last century with payment in installments for fifty years. A little over ten dessiatines. There was just that on the estate: a hut nine by nine arshins with a cattle yard adjoining it, a hay shed, a bathhouse, a smithy. The work on the revival of this estate seemed to be progressing successfully, but there were also delays - one or the other is missing: you can’t buy or get a furnace view or a bath boiler, time is spent searching. That stop because of the straw for the roof - the rye on the state farm fields has not yet matured, and when it's time to reap, you will not suddenly find reapers in the village. Then there were no roofers nearby, who can, as was customary before, cover with straw “under the comb”. This is where things dragged on. No, it didn’t work out as quickly as planned. Yes, to be honest, I was not a supporter of hasty reconstruction. Hastily, certainly on time - this means not very good, and there is no need for such a thing. And yet, by the fall of 1987, the estate had been largely revived. More than a hundred birches were planted in the spring, and all of them took root, had a good growth. Behind the forge, to the west, in the same place, a small piece of spruce forest of sixty-five fir-trees two meters high was green. Eight broadleaf linden trees were planted; both oak and tree-like forest rowan grow in the same place, and to the south, behind the barn, an orchard of nine now fruit-bearing apple trees has been restored. Unfortunately, it was not possible to find the former varieties: box, sugar arcade, Moscow pear. There is a well on the estate and a reservoir in the form of a lake with an island in the center. The area of the memorial site is 2.6 hectares. Along the perimeter, like a living fence, they planted two thousand Christmas trees strictly along a line in three rows - they all took root.

All this was done, of course, with the help of the community of the area. Much attention was paid to the first secretary of the district committee of the party, Nikolai Vasilyevich Zhvats. Both military units and individual enthusiasts from other areas helped. Podolsk resident Viktor Vasilievich Shiryaev came four times to take part in the restoration of the memorial. For the same purpose, our fellow countryman and my school friend Mikhail Methodievich visited from Leningrad

- 324 -Karpov - participated in planting trees, Ivan Sidorovich Bondarevsky from the city of Krasny Luch, Pyotr Trofimovich Solnyshkin from Skopin, Ryazan region, Nikolai Fedorovich Dyakov from Moscow, Taras Ivanovich Kononenko from Lipetsk. You can’t list them all, you can’t remember them all.

The opening of the museum was dedicated to the seventy-eighth birthday of Alexander Trifonovich. It was solemn, festive and crowded in those June days of 1988 on the estate of the revived farmstead. Hundreds of cars and thousands of festively dressed guests filled both the Zagorye estate and the village of Seltso. The meeting was opened by the first secretary of the Smolensk Regional Committee of the CPSU, Anatoly Aleksandrovich Vlasenko. Then our guest of honor from Moscow, writer Valery Vasilyevich Dementyev, spoke. They were tasked with cutting the ribbon in front of the entrance to the Alexander Tvardovsky memorial.

A large concert of amateur groups of writers and artists of Smolensk was given in a birch grove near the Selts House of Culture. This celebration was broadcast on television and radio.

Many years have passed since then. Thousands of visitors visited Zagorje: excursions, delegations, enterprise teams and educational institutions, individual visitors from different parts of the country. The path to Zagorje, to the place of origin national poet, will never be overgrown.

Events often occur in a person’s life that radically change one’s view of the surrounding reality. One of these events, unfortunately, is war. This terrible word makes us look with different eyes not only at the usual conditions of existence, but also at eternal values.

There are quite a lot of works about war in Russian literature, and one of the most famous is the poem “Vasily Terkin” by Alexander Trifonovich Tvardovsky.

During the Great Patriotic War, as a war correspondent, Tvardovsky was directly present on the battlefields. That is why all the works of this author make a huge impression on readers, captivating them with the reality of the events he describes.

The poem “Vasily Terkin” is a kind of eternal monument to the Russian soldier, his immortal feat. Tvardovsky emphasizes the real heroism of Soviet soldiers, the ability to withstand the days of difficult trials. The author remarkably succeeded in combining the main qualities of all defenders of the Motherland in the image of Vasily Terkin.

Perhaps the image of Vasily Terkin fell in love with readers because of the absence of lies and feigned patriotism, which is so often found in military works. His speeches most often have an ironic and playful tone. But when the conversation turns to the pain and suffering of one’s homeland, jokes give way to words of deep love and compassion:

I bent such a hook.

I've come so far

And I saw such torment,

And I knew such sadness!

Reading the “Book about a fighter”, you can notice one interesting fact. Terkin’s homeland, which he speaks of so reverently, is very similar to the homeland of thousands of other Russian fighters. Almost every soldier can say: “This is my village!” Vasily Terkin describes his native place in such a way that it is simply impossible to remain indifferent. He talks about the forest, where he and the boys collected nuts, built huts and hid from the rain, describes that wine spirit that makes you dizzy and sleepy. But then Vasily Terkin asks himself the question: “Father’s land, do you exist or not?” What if all this was destroyed long ago by enemies...

Terkin really wants to return home, hug his mother, see his homeland, talk about this and that with his fellow countrymen.

Mother earth, my dear,

My forest side

A land suffering in captivity!

I'll come - I just don't know the day,

But I will come, I will bring you back.

These lines make us believe that someday the war will definitely end. Russian people cannot give up to anyone those places that are so dear to their hearts. Moving further and further from its native lands, the human soul begins with unprecedented strength to rush to its origins, home, to its homeland:

Mother earth, my dear,

I have tasted your power,

How big my soul is,

From afar I was eager to see you!

But Terkin did not walk alone... Next to him, shoulder to shoulder, were other soldiers, just like himself. But now, very far from their homeland, experiencing all the hardships and hardships of the war, the fighters no longer separate their Caucasus and someone else’s Ukraine... They, as one, asked: “What is it, where is Russia?”

The “small” and “big” homelands intertwined together and became a single whole for all Russian soldiers... The soldiers, having survived all the trials that befell them, strive to quickly return to their homeland. They have only one cherished desire:

And it's only a mile to home,

Reach you alive

Show up in those areas:

- Hello, my homeland!

Tvardovsky in “The Book about a Fighter” managed to reflect the soul of the entire Russian people. All the feelings and thoughts put into the mouth of Vasily Terkin were the thoughts of all the soldiers who stood for their Motherland to the last drop of blood. Therefore, this poem was very popular among the soldiers. After all, only people who passionately loved their Motherland could endure all the hardships and trials of a grueling war, could win and survive in this terrible war!

Essay on literature on the topic: The theme of the “big” and “small” homeland (based on the poem “Vasily Terkin” by A. T. Tvardovsky)

Other writings:

- 1. Transformation of the former Vasya Terkin, a popular popular hero, into everyone’s favorite character. 2. The image of the Motherland in the poem. 3. The poem “Vasily Terkin” as an encyclopedia of war. 4. The author’s attitude towards his work. In addition to the poems and essays written by Tvardovsky during the winter campaign Read More ......

- A. T. Tvardovsky worked in the front-line press throughout the Great Patriotic War, and throughout the entire war period his most outstanding and popularly beloved poem “Vasily Terkin” (1941 - 1945) was created. At first, the brave soldier Vasya Terkin appeared as the hero of poetic feuilletons Read More ......

- The most important, decisive events in the life of the country were best reflected in the poetry of Alexander Trifonovich Tvardovsky. In his works we see a deep realism in the depiction of events, the truthfulness of the characters created by the poet, and the accuracy of the people's words. Among his many works, the wartime poem “Vasily Read More ......

- At the very height of the Great Patriotic War, when our entire country was defending its homeland, the first chapters of A. T. Tvardovsky’s poem “Vasily Terkin” appeared in print, where a simple Russian soldier, “an ordinary guy,” was depicted as the main character. The writer himself recalled that the beginning of the work Read More......

- The poem “Vasily Terkin” was written by Tvardovsky based on the personal experience of the author - a participant in the Great Patriotic War. In terms of genre, this is a free chronicle narrative (“A book about a fighter, without beginning, without end...”), which covers the entire history of the war - from the tragic retreat to Victory. Chapters Read More......

- The main spatial concept of “Terkin” is the topos of Russia. This proper name appears seventeen times in the book - more often than other geographical names. Despite the fact that we did not take into account the repeatedly occurring definition of “Russian”, the words “homeland”, “ motherland" Russia as a state, as a country, Read More......