Report specificity of rhetorical argumentation. Rhetorical view on the specifics of argumentation Rhetorical argumentation speech means of proof

MOSCOW

AUTOMOBILE AND ROAD STATE TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY

(MADI)

Department of the Russian language of the main faculties

Student: Petrov A.V., group 4ZAP 2

Leader: Professor Chesnokova M.P.

Moscow 2011-2012

Definition of rhetoric

The first known definition of rhetoric was given in ancient Greece, where it was described as the ability to find possible ways of persuading about any given subject. Such a view of rhetoric as a science of the forms and methods of speech impact on the audience was developed and consistently presented in the treatises of Isocrates, Hermagorus, Apollodorus. Another approach is given by the Roman tradition, which considered rhetoric to be the science of "good speech", and this definition included both the requirement of persuasiveness of speech, and attention to expression, to verbal design. The further fate of rhetoric is connected with the strengthening of this trend - interest in form comes first, the beauty of expression becomes the main measure of practice. We owe this branch of rhetorical practice the widespread idea of rhetoric as a pompous "externally beautiful, but of little substance" work of speech. It was then that the expression "empty rhetoric" appeared and a stable negative attitude towards this term developed.

However, today it has become clear that it is not the word, not science that is to blame: everything depends on the content that we put into this word and which we are engaged in studying science. Our society needs rhetoric not as a science of decorating speech, but as a discipline that helps to learn how to intelligently express one's thoughts, to influence the audience through speech. Therefore, it is quite obvious that modern rhetoric should return as a whole to the Greek interpretation of the subject, resolutely put form at the service of content, because only in this case will it be able to cope with the important tasks that the time sets before it. It is from such positions that A.K. Avelichev: "Rhetoric is the science of methods of persuasion, various forms of predominantly linguistic influence on the audience, taking into account the characteristics of the latter and in order to obtain the desired effect."

Purpose of speech

The first classification of speeches by purpose was proposed by Aristotle in his famous Rhetoric. In addition to the purpose, it took into account the time and place of communication. On these grounds, Aristotle singled out deliberative, judicial, and epideictic speeches. At the same time, the deliberative speech, as he believed, is turned to the future, acts in the form of advice and aims to persuade to commit a certain action; judicial speech is turned to the past and aims to convince the defendant of the guilt or innocence; epideictic speech is addressed to the present and aims to praise or scold a person.

The most important task of speech

In addition to the task, the goal setting also includes the super-task of speech. “The term “super task” was introduced by Stanislavsky into the theory of theatrical art, and it means that hidden spring of action, which, according to the director’s intention, should keep the emotions of the audience in line with the director’s intention throughout the performance. The super task in a persuasive speech is also an element of art. Without it, the speech strategy will be directed only at the consciousness, the “head” perception of the speaker’s position by the listeners. “…” Of course, the listeners’ emotions are affected by the general harmony, persuasiveness of the evidence, and the rigidity of the conclusions. However, in order to induce people to reconsider not only their views, but also their behavior, to change their methods of action, a purposeful, cross-cutting, but very well hidden from direct perception super-task is needed, specially designed for the emotions of listeners, influencing not only the consciousness, but also the subconscious.”

Thus, The most important task of speech is a hidden idea that is suggested to listeners by influencing their feelings and subconsciousness. The most important task is never presented openly, but hidden in the subtext. Its content is in no way connected with the type of speech in terms of purpose and depends only on the intentions of the speaker. Therefore, cases are possible, for example, when a speaker makes an informational speech (task: "to acquaint the audience with the state of affairs in the trade union movement"), but at the same time has a persuasive super-task ("to convince listeners that the trade union movement plays an important role in modern social life") or even an incentive ("to encourage listeners to join trade unions"). This situation cannot be qualified as the presence of several tasks in speech. After all, a task is something that is declared and implemented in speech openly - such a task is always the same. The most important task is that, out of oratorical caution, the speaker does not impose directly, but inspires by indirect means.

Argumentation

The creation of a speech begins with the definition of a strategy for a future speech - finding a topic, analyzing the characteristics of the audience, determining the task of speech, formulating a thesis and conducting its conceptual analysis. These actions help create the idea of speech, determine the direction of the main blow. This is the most important part of working on a speech, helping the future speaker to determine for himself the main content of the speech. However, after the speaker himself clearly understood to whom, why and what he would say, it was time to think about the audience, how to make the thesis of the speaker their property, to convince them of the correctness of their thoughts. These tasks are implemented at the tactical stage of working on a speech, which consists mainly in the fact that the speaker selects the material that, in his opinion, will help him realize his plan in the intended audience. The specificity of rhetorical argumentation is the subject of consideration.Traditionally, reasoning is described in writings on logic. There are many similarities between the understanding of argumentation in logic and rhetoric, but there are also very significant differences that need to be paid special attention. The comparison is also important because the logical understanding of argumentation is widely known, while the rhetorical understanding is still little known, which creates the danger of replacing rhetorical argumentation with evidence in the practice of mastering rhetoric. In order to avoid this undesirable phenomenon, it is first necessary to determine, as precisely as possible, what meaning logic and rhetoric attach to the concept of "argumentation".

The specifics of rhetorical argumentation

Argumentation in logic and rhetoric

A purely logical view of the problem of argumentation is presented, for example, by the following opinion: “If the process of argumentation in its abstract purity is a unity of logical and non-logical components aimed at a single goal - the formation of certain beliefs in someone, then it is usually resorted to in cases where the narrow-logical components for the addressee turn out to be insufficiently convincing for some reason and, as a result, the proof does not reach the goal. The non-logical components here take on the function of strengthening the process of proof and ensuring the desired effect. become sufficient, then the need for any extra-logical elements disappears. The process of argumentation thus passes into the process of proof. In this regard, the proof can be conditionally represented, if we use the mathematical term, as a "degenerate case" of argumentation, namely, as such an argumentation, the extra-logical components of which tend to zero. This implies the legitimacy of the position: if there is a proof that is perceived as such, then an argument that has in its composition other than purely discursive-logical components is not needed."This position is also characteristic of other works by logical specialists who consider argumentation to be a purely logical subject, necessary only when the audience does not immediately perceive the evidence presented and additional arguments are required, which should still remain within strictly rational framework. "Philosophical-ideological, axiological, psychological and other components" are allowed in the argument as secondary and only to the extent that "each of them satisfies the requirements of formal logic, its typical, standard schemes." And even the choice of this or that logical argument is determined not by the specifics of the intended audience, but by "near-scientific mythology", "fashion" and "requirements of an ideological nature."

The opposite position is taken by representatives of neo-rhetoric, in whose works argumentation is decisively declared the prerogative of rhetoric, and who consider argumentation one of the possibilities of speech influence on human consciousness. So, V.Z. Demyankov points out that, unlike proof, argumentation serves to win listeners over to one's side, and for this it is not necessary to resort to rational arguments. It is often enough to simply make it clear "that the position in favor of which the proponent speaks lies in the interests of the addressee; protecting these interests, one can still influence emotions, play on a sense of duty, on moral principles. Argumentation is one of the possible tactics for implementing the idea." This opinion goes back to a non-rhetorical assessment of the essence of argumentation by H. Perelman, who argued that "the area of argumentation is such assessments of arguments as plausibility, possibility and probability, taken in a meaning that cannot be formalized in the form of calculations. Any argumentation aims at bringing consciousnesses closer together, and thus presupposes the existence of intellectual contact." Thus, here we see a purely rhetorical view of the essence of argumentation, which is understood as "the possibility of speech impact on human consciousness", "part of the theory of achieving social understanding" and is opposed to logical impact. An important element of this position is the requirement to take into account the characteristics of the audience as an indispensable condition for the effectiveness of argumentation, which is actually a rhetorical factor that is not used in logic. Argumentation is evaluated in terms of relevance, which is also the responsibility of rhetoric, not logic.

However, it is clear that rhetoric cannot claim a monopoly on the consideration of argumentation. The distinction between logical and rhetorical in argumentation has a positive meaning for both sciences.

As a starting point for such a distinction, consider the point of view of V.F. Berkova: "All argumentation has two aspects - logical and communicative. In logical terms, argumentation acts as a procedure for finding and presenting for a certain position (thesis) expressing a certain point of view, support in other positions (grounds, arguments, arguments). In some cases, the thesis is based on the grounds in such a way that it is determined by the true content of the latter, as if filled with them. the basis "If p, then q, and if q, then r", then it is obvious that it is constructed from the elements included in this basis. It is this method of argumentation that is characteristic of science. Outside of science, the situation is usually different, and the thesis can be based on religious faith, the opinion of authority, the strength of tradition, the momentary mood of the crowd, etc. The ultimate goal of this process is the formation of this belief. Argumentation achieves this goal only if the recipient: a) perceived, b) understood and c) accepted the thesis of the argumentator. According to two aspects, the functions of argumentation are distinguished: cognitive and communicative.

The distinction between the logical aspect of argumentation, focused on the cognitive function, and the rhetorical aspect, focused on the communicative function, will help to correctly understand the essence and purpose of the argumentation, to understand its corresponding components.

The ratio of evidence and suggestion

The relationship between the cognitive and communicative aspects of speech can change significantly. Moreover, the case when only the logical aspect is relevant is called proof, and the case when only the communicative aspect is relevant is called suggestion.Proof- the concept is predominantly logical. This is a set of logical methods of substantiating the truth of a judgment with the help of other true and related judgments. Thus, the task of proof is the destruction of any doubts about the correctness of the thesis put forward. When constructing a proof, the speaker uses rational (logical) arguments: scientific theories and hypotheses, facts, statistics. All these arguments must withstand the test of truth, be based on knowledge, consist of impersonal judgments.

Suggestion- the concept is predominantly psychological. This is the imposition of a ready-made opinion on the addressee by influencing the subconscious. Thus, the task of suggestion is to create in the addressee a feeling of voluntary perception of someone else's opinion, its relevance, attractiveness. When constructing a suggestion, the speaker uses emotional (rhetorical) arguments: psychological, figurative, references to authorities, etc. These arguments are based on assessments and norms, must seem plausible, rely on opinions and appeal to the individual.

etc.................

2 . - Well... Tell us what you know about the Vyatka province.

- Vyatka province, - said Chelnokov, - is distinguished by its size. This is one of the largest provinces of Russia ... In terms of its area, it occupies a place equal to ... Mexico and the state of Virginia ... Mexico is one of the richest and most fertile countries in America, inhabited by Mexicans who are clashes and battles with Guerillas. The latter sometimes enter into an agreement with the Indian tribes of the Shavnias and Hurons, and woe to that Mexican who ...

“Wait,” the teacher said, peering out from behind the magazine. - Where did you find the Indians in the Vyatka province?

- Not in the Vyatka province, but in Mexico.

- Where is Mexico?

- In America.

- And the Vyatka province?

- In Russia.

- So you tell me about the Vyatka province.

- Hmm! The soil of the Vyatka province has little chernozem, the climate there is harsh and therefore arable farming is difficult. Rye, wheat and oats are the main things that can grow in this soil. Here we will not meet any cacti, or aloes, or tenacious vines, which, spreading from tree to tree, form an impenetrable thicket in virgin forests, which the tomahawk of the brave pioneer of the Far West overcomes with difficulty, which boldly makes its way forward under the unceasing cries of monkeys, multi-colored parrots, announcing the air ...

I hear one of them. Unfortunately, he does not say anything about the Vyatka province. (A. Averchenko)

3 . Some people's deputies of the USSR, who are the chairmen of the Soviets and at the same time the first secretaries of the regional committees of the Communist Party, do not give the floor to the people's deputies of the RSFSR at their sessions, in particular, Comrade Ivan Sergeevich Boldyrev. I propose that the Congress vote to confirm the possibility of the People's Deputies of the USSR being in the meeting room of the Congress, and not on the balcony. I spoke at the session on this question and explained to Comrade Boldyrev that people's deputies of the USSR could be in the hall, but he believed that they could not be in the hall. Therefore, I ask the Congress to confirm the possibility of their being in the hall by a vote of the Congress. (A.V. Kulakovsky)

4 . Journalist: The ultimatum adopted by the UN concerned both Serbs and Croats. Why did the air strikes affect only the Serbs?

A person from the Foreign Ministry: The fact is that it was a bilateral ultimatum, which involved the withdrawal of troops from the demilitarized zone. Now all Serbian weapons depots are blocked and cannot be used. I hope that after this outbreak of violence, the parties will sit down at the negotiating table. (TV, "Vremya", 05/27/1995)

5 . He gave a speech like this:

- I really like it here. I have never lived in a forest; but I once had a tame possum, and on my last birthday I turned 9 years old. I can't stand going to school. The rats ate 16 eggs from Jimmy Talbot's aunt's pockmarked hen. Are there real Indians here in the forest? I want more gravy. Why does the wind blow? Because the trees sway? We had 5 puppies. Hank, why is your nose so red? My father's money seems to be invisible. Are the stars hot? On Saturday I beat Ed Walker twice. I don't like girls! You can't really catch a toad, except with a string. Bulls roar or not? Why are oranges round? Do you have beds in the cave? Amos Murray - six-fingered. A parrot can talk, but monkeys and fish can't. A dozen is how much? (O'Henry)

6 . Bourgeois propaganda proclaims: "We have complete freedom: if you want, vote for a communist; if you want, choose a defender of the capitalist system." So the "great American" Abraham Lincoln was the son of a carpenter - bourgeois ideologists will not fail to remind. The falsity of such an argument becomes obvious as soon as we turn to the real facts of the same American reality. It is said that Abraham Lincoln, running for the House of Representatives, spent 75 cents on the entire election campaign, exposing voters to a barrel of cider. Today it is remembered as a historical curiosity. Now, in order to get to the Capitol, and even more so to The White house, hundreds of thousands, millions of dollars are needed. In the age of aviation, television, total advertising, they go to saturate the jet engines of special liners, buy airtime, maintain a huge staff of assistants - From writers of speeches to specialists in diction and gestures ... (E.A. Nozhin)

Task number 16. Determine the purpose of the speeches. Find a thesis in each of them and draw up a plan-outline.

1 . A monument to Pushkin has been erected: the memory of the great national poet is immortalized, his merits are attested. Everyone is happy. We saw yesterday the delight of the public, they rejoice only when merits are given their due, when justice triumphs. It is hardly necessary to speak about the joy of writers. From the fullness of my overjoyed soul, I also allow myself to say a few words about our great poet, his significance and merits, as I understand them.

On this holiday, every writer is obliged to be a speaker, is obliged to loudly thank the poet for the treasures that he bequeathed to us. The treasures given to us by Pushkin are indeed great and invaluable. The first merit of a great poet is that through him everything that can become wiser becomes wiser. In addition to pleasure, in addition to forms for expressing thoughts and feelings, the poet also gives the very formulas of thoughts and feelings. The rich results of the most perfect mental laboratory are being made public property. The highest creative nature attracts and equalizes everyone. The poet leads the audience to a land of grace unfamiliar to her, to some kind of paradise, in the subtle and fragrant atmosphere of which the soul rises, thoughts improve, feelings are refined. Why is every new work from the great poet so eagerly awaited? Because everyone wants to think and feel loftily with him, everyone expects that he will tell me something beautiful, new, which I do not have, which I lack, but he will say, and this will immediately become mine. This is why love and worship of great poets, this is why great sorrow at their loss, emptiness, mental orphanhood is formed: there is no one to think, no one to feel.

But it is easy to recognize the feeling of pleasure and delight from an elegant work, and it is rather difficult to notice and trace one's mental enrichment from the same work. Everyone says that he likes this and that work, but a rare person realizes and admits that he has grown wiser from it. Pushkin was admired and wised up, admired and wised up. Our literature owes its mental growth to him. And this growth was so great, so rapid, that the historical sequence in the development of literature and public taste was, as it were, destroyed, and the connection with the past was severed. This leap was not so noticeable during the life of Pushkin, although his contemporaries considered him a great poet, they considered him their teacher, but their real teachers were people of the previous generation, with whom they were connected with a feeling of boundless respect and gratitude. No matter how much they loved Pushkin, but still, in comparison with older writers, he seemed to them still young and not quite solid, to recognize him alone as the culprit of the rapid forward movement of Russian literature meant for them to offend respectable, in many respects very respectable people. All this is understandable, and it could not be otherwise, but the next generation, brought up exclusively by Pushkin, when they consciously looked back, saw that his predecessors and many of his contemporaries were no longer even past, but long past for them. That's when it became noticeable that Russian literature in one person has grown for a whole century. Pushkin found Russian literature in the period of its youth, when it still lived on other people's models and worked out forms based on them, devoid of living, real content - and what then? His works are no longer historical odes, not the fruits of leisure, solitude, or melancholy, he ended up leaving us samples equal to those of mature literature, samples perfect in form and original, purely folk content. He gave seriousness, raised the tone and significance of literature, brought up the taste in the public, conquered it and prepared readers and connoisseurs for future writers.

Another beneficence bestowed on us by Pushkin, in my opinion, is even more important and even more significant. Before Pushkin, our literature was imitative - along with forms, it took from Europe various trends historically established there, which had no roots in our life, but could be accepted, as much transplanted was accepted and rooted. The relationship of the writers to reality was not direct, sincere, the writers had to choose some conventional angle of view. Each of them, instead of being himself, had to tune in to some way. Outside these conditional directions, poetry was not recognized, originality would be considered ignorance or freethinking. The release of thought from the yoke of conventional methods is not an easy task, it requires enormous strength. A solid foundation for the liberation of our thought was laid by Pushkin, he was the first to treat the themes of his works directly, directly, he wanted to be original and was, was himself. A great writer leaves behind a school, leaves followers. And Pushkin left school and followers. What is this school that he gave to his followers? He bequeathed to them sincerity, originality, he bequeathed to everyone to be himself, he gave courage to any originality, he gave courage to the Russian writer to be Russian. After all, it's just easy to say! After all, this means that he, Pushkin, revealed the Russian soul. Of course, for his followers, his path is difficult: not all originality is so interesting as to be shown and occupied by it. But on the other hand, if our literature loses in quantity, it wins in quality. Few of our works go to the evaluation of Europe, but even in this little the originality of Russian observation, the original way of thinking has already been noticed and appreciated. Now it only remains for us to wish that Russia would produce more talents, to wish the Russian mind more development and space, and the path along which talents should follow was indicated by our great poet. (A.N. Ostrovsky, 06/07/1880)

2 . Courage is the glory of the city, beauty is the body, rationality is the spirit, truthfulness is the cited speech; anything to the contrary is just blasphemy. We owe a man and a woman, a word and a deed, a city and an act, if they are commendable - to honor with praise, if they are not praiseworthy - to defeat with mockery. On the other hand, it is equally foolish and untrue to condemn what is praiseworthy, and to praise what is worthy of ridicule. Here I have to reveal the truth at the same time, and denigrate those who discredit - discredit that Helen, about whom, unanimously and unanimously, both the true word of the poets, and the glory of her name, and the memory of troubles have been preserved to us. I set out, in my speech, citing reasonable arguments, to remove the accusation from the one who had to hear rather bad things, to show her detractors as lying, to reveal the truth and put an end to ignorance.

But having passed the old times in my present speech, I will pass to the beginning of the commendation I have undertaken and for this I will state the reasons for which it was just and proper for Helen to go to Troy.

Was it by chance, by the command of the gods, by necessity, by legalization, did she do what she did? Was she abducted by force, or coaxed by speech, or embraced by love?

If we accept the first, then the accused cannot be guilty: God's providence is not a hindrance to human thoughts - by nature, not a weak obstacle to the strong, but strong power and a leader to the weak: the strong lead, and the weak follow. God is stronger than man and in power and wisdom, like everything else: if we must attribute guilt to God or chance, then Helen must be recognized as free from dishonor.

If she is kidnapped by force, illegally overpowered, unjustly offended, then it is clear that the kidnapper and the offender are guilty, and the kidnapped and offended is innocent of her misfortune. What barbarian acted so barbarously, let him be punished for it in word, right and deed: his word is accusation, right is dishonor, deed is revenge. And Elena, having been subjected to violence, having lost her homeland, having remained an orphan, doesn’t she deserve more pity than reproach? He did, she endured the unworthy; really, she is worthy of pity, and he of hatred.

If it was her speech that convinced her and captured her soul by deceit, then here it is not difficult to defend her and exonerate her from this guilt. For the word is the greatest lord: it looks small and imperceptible, but it does wonderful deeds - it can stop fear and turn away sadness, cause joy, increase pity. What prevents us from saying about Elena that she left, convinced by her speech, she left like the one that does not want to go, as if she were illegal if she submitted to force and was kidnapped by force. She allowed herself to be possessed by conviction; and the conviction that has taken possession of it, although it does not have the appearance of violence, coercion, but has the same force. After all, the speech that convinced the soul, having convinced it, makes it obey what was said, sympathize with what was done. The one who convinces is just as guilty as the one who forced; She, convinced, as if forced, in vain hears reproach in her speeches.

Now, in the fourth speech of the fourth, I will deal with her accusation. If love has done this, then it is not difficult for her to escape the charge of the crime she is said to have committed. If Eros, being the god of the gods, possesses divine power, how can the weakest from him and fight back and defend himself! And if love is only suffering for human diseases, an eclipse of spiritual feelings, then it should not be condemned as a crime, but as a misfortune, a phenomenon should be considered. She comes as soon as she arrives, fate catching - not thoughts by command, compelled to yield to the oppression of love - not born by conscious force of will.

How can it be considered fair if Elena is reviled? Whether she did what she did, defeated by the power of love, whether convinced by a lie of speeches or carried away by obvious violence, or forced by the coercion of the gods - in all these cases there is no fault on her. (Gorgias)

Task number 17. Here are 6 options for outline plans on the same topic (about etiquette). However, the specific topics of speeches are different. Formulate the topic, task and thesis of each speech. Determine in which audience they could be delivered. Edit each outline to fit the task and characteristics of the audience, as well as the thesis of the speech.

Option 1.

I. The ability to master the rules of etiquette has always been valued and appreciated.

II. The rules of etiquette should become the second multiplication table for the Russian people.

1) The rules of etiquette must be taught from school.

2) It is necessary to start training from an early age, because it is easier to teach than to retrain.

3) Teaching etiquette should take place in the family from an early age.

4) Even in a friendly company, at least a basic knowledge of the rules of etiquette is necessary.

III. The rules of etiquette need to be revived in our time with a low culture.

Option 2.

I. If you want to be respected, respect others.

II. Out of respect for etiquette.

1) Forgotten rules of etiquette lead to low culture.

2) Education of etiquette is the future that will help a person become cleaner, brighter.

3) What are the rules of etiquette.

III. The rules of etiquette not only cannot be abandoned, but they must be revived.

Option 3.

I. The low level of etiquette in our society as a purposeful action.

II. The complete absence of etiquette will contribute to a decrease in the cultural level, the destruction of traditions that have developed over the centuries.

III. Etiquette needs to be revived, not abandoned.

IV. Etiquette and human behavior in society.

Option 4.

I. Introduction. The ability to master the rules of etiquette is an indicator of a person's culture.

II. main part

1) Soviet Union became a victim of the assertion that we do not need etiquette.

2) Having opened a window to the world, we cannot remain uncivilized representatives of our country.

3) The rules of etiquette open the veil to the world of wonderful communication and mutual understanding.

III. Conclusion. At all times, in any society, there were rules of etiquette. They contributed to a high level of relationships between people.

Option 5.

I. Etiquette as a necessary source of communication between people.

II. Violation of etiquette can lead to irreparable consequences(severance of diplomatic relations, war, etc.)

1) Today there is no etiquette as such:

a) the behavior of deputies at Congresses and in the Duma.

b) the behavior of people in transport.

2) Instilling the rules of etiquette in children from an early age.

III. Etiquette is one of the foundations of culture.

Option 6.

I. It is necessary to revive the rules of etiquette in everyday communication.

II. The development of etiquette contributes to the improvement of morality and culture of people.

1) There are few people in our society who follow the rules of etiquette for certain reasons.

2) Etiquette is a framework that defines the various qualities of a person.

3) A norm that smooths out the friction and contradictions that arise between people.

4) A measure that restrains negative emotions and affirms the correct relationship between people.

5) This is a tradition gradually developed by mankind, the history of relationships.

6) In everything, a measure is needed, beyond which etiquette makes communication difficult.

III. As flowers decorate our lives, so etiquette brings joy to gray everyday life.

ARGUMENTATION

The creation of a speech begins with the definition of a strategy for a future speech - finding a topic, analyzing the characteristics of the audience, determining the task of speech, formulating a thesis and conducting its conceptual analysis. These actions help create the idea of speech, determine the direction of the main blow. This is the most important part of working on a speech, helping the future speaker to determine FOR HIMSELF the main content of the speech. However, after the speaker himself clearly understood to whom, why and what he would say, it was time to think about the listeners, how to make the thesis of the speaker their property, to convince them of the correctness of their thoughts. These tasks are implemented at the tactical stage of working on a speech, which consists mainly in the fact that the speaker selects the material that, in his opinion, will help him realize his plan in the intended audience. The specificity of rhetorical argumentation is the subject of consideration in this chapter.

Traditionally, reasoning is described in writings on logic. Between the understanding of argumentation in logic and rhetoric, of course, there is much in common, but there are also very significant differences that need to be paid special attention, since this will save us from an incorrect assessment of this phenomenon. Comparison is also important because the logical understanding of argumentation is widely known, replicated in many textbooks and scientific articles, while rhetorical understanding is still little known, which creates the danger of replacing rhetorical argumentation with evidence in the practice of mastering rhetoric. In order to avoid this undesirable phenomenon, it is first necessary to determine, as precisely as possible, what meaning logic and rhetoric attach to the concept of "argumentation".

The specifics of rhetorical argumentation

§24. Argumentation in logic and rhetoric

§ 24. A purely logical view of the problem of argumentation is represented, for example, by the following opinion: “If the process of argumentation in its abstract purity is a unity of logical and non-logical components aimed at a single goal - the formation of certain beliefs in someone, then it is usually resorted to in cases where the narrow-logical components for the addressee turn out to be insufficiently convincing for some reason and, as a result, the proof does not reach the goal. The extra-logical components here take on the function of strengthening the process of proof and ensuring the desired effect. But when logically If the components themselves become sufficient, then the need for any extra-logical elements disappears. The process of argumentation thus passes into the process of proof. In this regard, the proof can be conditionally represented, if we use the mathematical term, as a "degenerate case" of argumentation, namely, as such an argument, the extra-logical components of which tend to zero. This implies the legitimacy of the position: if there is a proof, which as such is perceived, then an argumentation that has in its composition, in addition to purely discursive-logical, also other components, not needed."

This position is also characteristic of other works by logical specialists who consider argumentation to be a purely logical subject, necessary only when the audience does not immediately perceive the evidence presented and additional arguments are required, which should still remain within strictly rational framework. "Philosophical-ideological, axiological, psychological and other components" are allowed in the argument as secondary and only to the extent that "each of them satisfies the requirements of formal logic, its typical, standard schemes." And even the choice of this or that logical argument is determined not by the specifics of the intended audience, but by "near-scientific mythology", "fashion" and "requirements of an ideological nature."

The opposite position is taken by representatives of neo-rhetoric, in whose works argumentation is decisively declared the prerogative of rhetoric, and who consider argumentation one of the possibilities of speech influence on human consciousness. So, V.Z. Demyankov points out that, unlike proof, argumentation serves to win listeners over to one's side, and for this it is not necessary to resort to rational arguments. It is often enough to simply make it clear "that the position in favor of which the proponent speaks lies in the interests of the addressee; protecting these interests, one can still influence emotions, play on a sense of duty, on moral principles. Argumentation is one of the possible tactics for implementing the idea." This opinion goes back to a non-rhetorical assessment of the essence of argumentation by H. Perelman, who argued that "the area of argumentation is such assessments of arguments as plausibility, possibility and probability, taken in a meaning that cannot be formalized in the form of calculations. Any argumentation aims at bringing consciousnesses closer together, and thus presupposes the existence of intellectual contact." Thus, here we see a purely rhetorical view of the essence of argumentation, which is understood as "the possibility of speech impact on human consciousness", "part of the theory of achieving social understanding" and is opposed to logical impact. An important element of this position is the requirement to take into account the characteristics of the audience as an indispensable condition for the effectiveness of argumentation, which is actually a rhetorical factor that is not used in logic. Argumentation is evaluated in terms of relevance, which is also the responsibility of rhetoric, not logic.

However, it is clear that rhetoric cannot claim a monopoly on the consideration of argumentation. The distinction between logical and rhetorical in argumentation has a positive meaning for both sciences.

As a starting point for such a distinction, consider the point of view of V.F. Berkova: "All argumentation has two aspects - logical and communicative. In logical terms, argumentation acts as a procedure for finding and presenting for a certain position (thesis) expressing a certain point of view, support in other positions (grounds, arguments, arguments). In some cases, the thesis is based on the grounds in such a way that it is determined by the true content of the latter, as if filled with them. the basis "If p, then q, and if q, then r", then it is obvious that it is constructed from the elements included in this basis. It is this method of argumentation that is characteristic of science. Outside of science, the situation is usually different, and the thesis can be based on religious faith, the opinion of authority, the strength of tradition, the momentary mood of the crowd, etc. The ultimate goal of this process is the formation of this belief. Argumentation achieves this goal only if the recipient: a) perceived, b) understood and c) accepted the thesis of the argumentator. According to two aspects, the functions of argumentation are distinguished: cognitive and communicative.

The distinction between the logical aspect of argumentation, focused on the cognitive function, and the rhetorical aspect, focused on the communicative function, will help to correctly understand the essence and purpose of the argumentation, to understand its corresponding components.

§25. The ratio of evidence and suggestion

§ 25. The relationship between the cognitive and communicative aspects of speech can change significantly. Moreover, the case when only the logical aspect is relevant is called proof, and the case when only the communicative aspect is relevant is called suggestion.

Proof is a predominantly logical concept. This is a set of logical methods of substantiating the truth of a judgment with the help of other true and related judgments. Thus, the task of proof is the destruction of any doubts about the correctness of the thesis put forward. When constructing a proof, the speaker uses rational (logical) arguments: scientific theories and hypotheses, facts, statistics. All these arguments must withstand the test of truth, be based on knowledge, consist of impersonal judgments.

Suggestion is a predominantly psychological concept. This is the imposition of a ready-made opinion on the addressee by influencing the subconscious. Thus, the task of suggestion is to create in the addressee a feeling of voluntary perception of someone else's opinion, its relevance, attractiveness. When constructing a suggestion, the speaker uses emotional (rhetorical) arguments: psychological, figurative, references to authorities, etc. These arguments are based on assessments and norms, must seem plausible, rely on opinions and appeal to the individual.

From this follow all the other differences that are at different poles of the influencing communication of evidence and suggestion. The proof is addressed to the thesis and aims to substantiate its truth. If the speaker has succeeded in showing by logical methods that smoking is unhealthy or that the firm's offerings are the best, he considers his task of proof accomplished. In this case, he is not interested in the life of proven truth. Whether the listener accepted it and how it influenced his actions does not matter. "This approach to argumentation ... is based on two assumptions. Firstly, the participants in the discussion exclude motives of personal interest from it. Secondly, the unity of the psychological decision-making mechanism is assumed: intuition and deduction, according to Descartes, as a clear and distinct perception of the subject and the use of uniform rules and symbols, is based on the idea of the same rationality of all people, differing only in the strength of the mind. "

The suggestion is addressed to the audience and aims, by influencing the sensual and emotional spheres of a person, to force them to accept the proposed ideas and be guided by them in practical matters. Who among smokers does not know about the dangers of smoking? But they continue to smoke, despite all the (well known to them) perniciousness of their passion. The speaker, resorting to suggestion, arouses in this situation a feeling of self-preservation, fear or disgust, etc., and thereby achieves the abandonment of a bad habit; or, appealing to personal interests, induces the audience to sign a contract with his own firm. If the effectiveness of logical proof depends on the truth of the arguments themselves, then the effectiveness of suggestion may depend to a decisive extent not on the content of speech, but on such extraneous points as a) the tone used by the speaker (confident - uncertain, respectful - cheeky, etc.); b) information about the speaker, known to the audience before his speech (specialist - non-specialist, director - subordinate, etc.); c) the degree of resistance of the audience to the arguments given (I have a prejudice against your company - I heard only good things about it, etc.).

The distinction between proof and suggestion is based on the existence of two types of reasoning, identified by Aristotle: analytical and dialectical. Detailed description analytical judgments are found in the First and Second Analysts, where the foundation of formal logic is laid. Dialectical inferences are considered by Aristotle in the Topic and Rhetoric, where he describes their essence and predominant scope: “There is a proof when an inference is built from true and first [propositions] or from those, knowledge of which originates from certain first and true [provisions]. Dialectical reasoning is built from plausible [provisions]. True and first [provisions] are those that are reliable not through others [positions], but through themselves. For the principles of knowledge do not need to be asked "why", and each of these principles must be reliable in itself. Plausible is what seems right to all or most people, or wise - to all or most of them or the most famous and glorious. "

Thus, according to Aristotle, proof is based on truth, suggestion is based on opinion, on what seems plausible to the audience. Further, Aristotle writes about the essence of plausibility: “No reasonable person will put forward in the form of provisions that no one seems right, and will not put forward as a problem what is obvious to all or most people. After all, the latter would not cause any bewilderment, and no one would assert the former. For what the wise believe can be considered plausible, if it is not contrary to the opinion of the majority of people. Dialectical positions are also similar to plausible, and offered as contradictory to those that are opposite to those considered plausible, as well as opinions consistent with the acquired arts. Thus, true statements are those that correspond to objective reality, and plausible statements are those that are perceived as true, that is, that the audience believes. These concepts may or may not coincide. Thus, the argument "because the Earth revolves around the Sun" is true and seems quite plausible to a modern listener, but in antiquity (to the same Aristotle) it seemed absolutely implausible, although it was just as true as it is now. The speaker's claim that he saw aliens, theoretically reasoning, may well turn out to be true, but is perceived by many audiences as implausible. On the other hand, the statement that Jesus, the son of God, lived on earth may well not correspond to the truth (this is exactly what representatives of other faiths think), but a huge number of people believe this (and therefore consider it plausible).

ARGUMENTATION OF JUDICIAL SPEECH

Introduction 3

1. The concept of argumentation 5

2. Rhetorical look at the specifics of argumentation 6

3. Ethical reasoning 7

4. Strategies 9

5. The principle of constructing a system of rhetorical argumentation on

example of defensive speech 11

Conclusion 14

References 15

Introduction

Argumentation has many aspects that serve as the subject of research - in various sciences - linguistics, rhetoric, philosophy, logic, psychology, in a number of social sciences, etc. None of the sciences can fully cover the phenomenon of argumentation precisely because for this it needs to go beyond its subject.

Argumentation studies are carried out within the framework of argumentation theory, linguistic pragmatics, discourse theory, cognitive semantics, etc. (G.Z. Apresyan, N.D. Arutyunova, A.N. Baranov, B.F. Gak, G.P. Grice, T.A. van Dijk, V.I. Karasik, Yu.N. Karaulov, E.S. Kubryakova, I.A. Sternin, etc.). But despite a large number of studies, the rhetorical aspects of this problem are given unreasonably little attention.

The choice of the rhetorical direction of the study of argumentation is due to the complex nature of rhetoric. According to I. Kraus, "rhetoric shows an amazing ability to fill the gap created by the ever-deepening specialization of the sciences." Rhetoric has become an integral area, covering the problems of creating speech; and ways of exerting influence, it "describes the process that goes from the communicative task to the actual message, then to the integration of the form and content of the text" .

Strategy is recognized as the basic unit of argumentation. For each genre, a general strategy can be defined, arising from the specifics of the genre itself, and private strategies, the choice of which depends on the desire of the speaker. According to the main intention, all strategies can be defined as ethical, rational or emotional.

The relevance of the study is due to the important social role argumentation of a judicial defensive speech and is determined by the following aspects: the rhetorical characteristics of the argumentation of a judicial speech, the study of which is very relevant for identifying the essential features of rhetorical argumentation in general, have not yet been the subject of scientific research; the basic rhetorical characteristic of the argumentation of a judicial speech is the presence of a hierarchy of values, the study of which makes a certain contribution to the solution of some problems of the linguistic theory of values-linguoaxiology, the most important component of the rhetorical argumentation of judicial speech is rational; (logical) component, the study of which is important for the theory of logical argumentation, a significant part of rhetorical argumentation, judicial speech is an emotional component, the study of which as a full-fledged component of argumentation makes a significant contribution to the theory of speech impact.

The concept of argumentation

IN Lately In Russian and foreign science, there is an increasingly persistent interest in argumentation, which is understood as an interdisciplinary field of the humanities. This interest is due to the fact that argumentation is present as an integral component not only in any act of communication, but also in the most various fields human knowledge. Increased attention to the problems of argumentation leads to the unification of the efforts of scientists from different directions to overcome the one-sidedness of the study of this complex phenomenon. Gradually comes the understanding that argumentation is primarily a process of communication, both verbal and non-verbal, based on the rational, emotional and even existential foundations of the human personality. Today, in the theory of argumentation, psychological and linguistic mechanisms are studied, which are by no means limited to the sphere of the rational, the field of thinking.

However, the difficulty lies in the fact that, despite the generally recognized interdisciplinarity of the emerging theory of argumentation, it is influenced either by logic (according to tradition) or pragmalinguistics. In the first case, there is a clear tendency to transfer the methods and forms characteristic of the exact sciences to the humanities. In the second case, special attention is paid to the form, grammatical ways of expressing certain intentions. Moreover, if the first direction is still trying to somehow interact with rhetoric, then the second usually strongly dissociates itself from it: .

At the same time, rhetoric was conceived by Aristotle precisely as a science responsible for finding arguments suitable for specific situations of communication. It is no coincidence that the founder of the theory of argumentation called his science "neorhetoric", since he understood that argumentation is the heart of rhetoric.

In this regard, there is now an urgent need to eliminate this flagrant injustice and show the role of rhetoric in the formation of the theory of argumentation.

A rhetorical look at the specifics of argumentation

The rhetorical view on the specifics of argumentation is due to its purely teleological nature: the ultimate goal of the theory here is always supposed to provide practical assistance to the speaker, the development of such a concept that would lead in practice to optimize the impact on the audience. The key concept of rhetoric is "impact", which is considered as the goal and result of speech action and manifests itself in the form of a new psychological state of the addressee - new knowledge, mood, agreement with the proposed point of view, desire to act in a certain way.

In this regard, since the time of Aristotle, it has been assumed that, in addition to the purely rational elements studied by logic, influencing speech must necessarily contain ethical and psychological components, consisting of the values of the author and appeal to the feelings of the audience. These components were commonly described in rhetoric as ethos, logos, and pathos.

Ethos is the moral (ethical) basis of speech (mores). Traditionally, this is mainly considered the appearance of the speaker, that oratorical mask that the speaker considers it necessary to present to the audience in order to achieve mutual understanding. However, it seems that ethos should be understood more broadly, as all ethical aspects of speech. The importance of the ethical component of the argumentation is determined by the fact that the survival of a person as a genus and species is conditioned by reflexive acts of reflecting oneself in the world, and this reflection is initially ethical: “And God saw that it was good ...”, - says the first chapter of the Bible (Gen. 1.10-15) - the primary source of Christian ethics.

From a cognitive point of view, the role of ethical argumentation is that with its help it is possible to form certain models. social behavior, since it is a kind of mechanism for the interaction of thinking and speech (language). Argumentation is not just a way of reasoning expressed in speech, but also a “tool” that allows a person to carry out effective behavior in social environment. It acts as a mediator in the development of social representations and models of conditioned social behavior.

Logos is an idea, the content (logical) side of speech (arguments). Logos is responsible for the audience's rational understanding of the essence and circumstances of the thesis. “In private rhetoric, methods of argumentation are studied that are characteristic of specific types of literature, for example, theological, legal, natural science, and historical argumentation. In general rhetoric, the method of constructing an argument in any kind of word is studied.

Paphos is a means of influencing the audience (the psychological side of speech, passion). To achieve the consent of the listeners, it is necessary not only to understand, but also to sympathize with the ideas of the speaker. Emotional arguments allow you to influence the feelings and desires of the listeners. Figurative thinking is older than logical, reasoning. Because of this, images penetrate deeply into consciousness, and logical forms remain on its surface, performing the function of scaffolding around the building of thought.

Ethical reasoning

Ethical reasoning stands apart from the other two branches. Many authors do not distinguish this category of arguments at all; sometimes such arguments are combined with emotional ones, at other times they are combined with rational ones. The main disputes in all areas of argumentation theory are over the division of rational (logos) and emotional (pathos) branches of argumentation.

The universality of the old rhetorical principle of the need to appeal to reason, feeling and will for the best impact on the audience is also confirmed in modern science. So, V.I. Karasik notes that the unit of knowledge relevant to the linguistic personality - the concept - has three main components: conceptual, figurative and value.

Further, within these traditional areas, the main units of argumentation should be defined. The most optimal such unit, which is most appropriate for the tasks of the rhetorical description of the argumentation, is the strategy, which is the planning of the speaker's activity, which consists in choosing certain steps of the argumentation based on optimality criteria. This is organically related to the general understanding of discourse, which is not the sum of arguments, but has a penetrating strategic essence. Moreover, drawing up a strategy cannot be identified with the creation of a speech plan (still so beloved by many authors of textbooks on rhetoric). Strategy is the principle of all activities of the speaker, constantly adjusting his plans in accordance with changing situations, since he constantly has to “choose from a certain number of alternative options such a move that seems to him the“ best answer ”to the actions of others.

The points of contact between the theory of speech genres and the theory of speech strategies are pointed out by O.S. Issers, which lists the parameters that bring together the concepts of "strategy" and "speech genre": the communicative goal as a constitutive feature, the image of the author, the concept of the addressee, predicting the possible reactions of the interlocutor, etc.

For the theory of rhetorical genres, the concept of strategy is even more necessary. So, if "the goals of speech acts and - in most cases - speech genres are limited to a specific communicative situation, episode", then for rhetorical genres, as well as for strategies, the goals "are long-term, calculated on the final result" [ibid., p. 73]

Strategies

Strategies used for rhetorical purposes can be defined as rational (having predominantly logical elements of influence), value (having predominantly ethical elements of influence) and emotional (having predominantly psychological elements of influence).

The strategies that form the basis of speech influence in a particular rhetorical genre are formed into a system. The first level of this system is formed by the general strategy corresponding to the general task of the genre. At the second level, private strategies appear that help to concretize the speaker's intention. Their set already largely depends on the desire of the speaker and the situation (and not just on the genre), however, here, for typical situations, there is also a typical set of possibilities. Each particular strategy has its own microtask, the solution of which makes a certain contribution to the solution of the general task of speech.

Strategies are complex units and are built from smaller units - tactics. "From the point of view of speech impact

strategy can only be considered through the analysis of tactics, since strategy is the art of planning based on correct and far-reaching forecasts. Tactics is the use of techniques, ways to achieve a goal, a line of conduct for someone. In this context, strategy is a complex phenomenon, and tactics is an aspect one. Thus, it is necessary to analyze aspectual phenomena in order to form a holistic view of the strategy.

Tactics is determined by "a system of operational methods, techniques and means used in the process of discussing the problem and aimed at the effective implementation of the set strategic goals by each of the participants in the dispute" . Tactics is the art of solving particular technical issues necessary for the implementation of a strategy. However, strategy is more complex than just the sum of tactics. Rather, it “does not “compose” of them, but determines their general direction. And vice versa: being to some extent parts of the strategy and unfolding linearly (in time and space), tactics do not precede the strategy, do not constitute it, but implement it.

In this regard, the question arises: does the speaker always consciously choose this or that strategy (tactics)? Doesn't a situation arise here when strategies can be found in influencing speech, but it is difficult to assume that the speaker was going to use them (as in speech one can always find and classify certain syntactic constructions, but it is unlikely that the speaker thinks about which constructions he uses)?

On this matter, researchers colloquial speech note the admissibility of the unconscious nature of the use of strategies: “The possible actualization of free schemes is due to the free use of structures without preliminary consideration of efficiency in the process of their selection and further application. In spontaneous speaking, the form cannot be preliminarily clearly defined by the speaker. Spontaneous construction (modeling) of form seems to us a natural process. At the same time, in institutional discourse, the use of certain strategies is conscious, arising from the specifics of the situation and genre. Of course, the speaker cannot reflect on the topic every time: what strategy to choose? However, automatism in the choice of strategies is achieved through hard training, awareness of which particular strategies are characteristic (mandatory) for a particular genre, that is, the genre strategic field is conventionally limited and defined.

An argument (lat. argumentum from the verb arguo - I show, I find out, I prove - an argument, proof, conclusion) we will call a fragment of a statement containing a justification for a thought, the acceptability of which seems doubtful.

To substantiate means to reduce a doubtful or controversial idea to an acceptable one for the audience. Acceptable can be a thought that the audience finds true or plausible, correct from the point of view of one or another norm, preferable from the point of view of their (and not the rhetor - the sender of the speech) values, goals or interests.

Argument structure

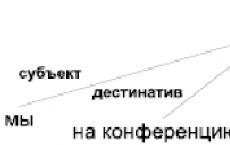

A rhetorical argument consists of: (1) position and (2) justification. Consider an example:

(1) "But is it really possible to find the truth? - One must think that it is possible if the mind cannot live without it, but it seems to live, and, of course, does not want to admit that it is deprived of life" .

Justification - a set of arguments, formulations of thoughts, through which the rhetor seeks to make the situation acceptable to the audience: ... if the mind cannot live without truth, but it seems to live, and, of course, does not want to recognize itself as deprived of life.

The position of the argument is the formulation of a thought that is put forward by a rhetorician, but presented to a dubious audience: But can one really find the truth? - You must think that you can

From the point of view of structure and content, the rhetorical argument includes three components: scheme, top, reduction.

The schema is the logical form of that particular argument. The construction of the scheme is subject to the rules of logic, and the scheme is a kind of logical backbone of the argument, which allows not only to judge the structure of a complex thought, but also to determine its correctness.

Common place or top - a position that is recognized as true or correct and on the basis of which a particular justification seems convincing. The top is contained or implied in the premises of the argument. The first top of the above argument: the mind lives by the truth. This position is not proved and does not follow from anywhere, but it seems obvious to the audience to which St. Philaret is addressing.

Argumentation can be dogmatic and dialectical. Dogmatic reasoning proceeds from provisions that are accepted as postulates and are considered self-evident and universal; these are the basic principles of scientific theory. Dialectical argumentation comes from premises that are convincing to the audience and are drawn from a variety of sources. Dialectical argumentation is fundamentally designed for a private audience.

Rhetorical argumentation is basically dialectical. This means, firstly, that the position of a rhetorical argument is a thought (thesis), which can be opposed by another thought (counterthesis). The counterthesis, however, does not always logically exclude the thesis.

Thesis: A committed a heroic deed; counterthesis: A violated military discipline. The premises substantiating the counterthesis are also not always a negation of the premises confirming the thesis, and may be quite compatible with them. If the audience is inclined to regard every owner as a dishonest person, it will be convincing, for example, such an argument: A set fire to the insured property because he wanted to receive an insurance premium. Here the premises will be implied: every owner is ready for a crime for the sake of profit; A is the owner; the fire destroyed the property A, insured for a large amount; therefore, etc.

But the opposite position can be justified not by the opposite in meaning (not every owner is ready for a crime for the sake of profit), but by a different, no less convincing premise, for example: A did not commit arson, because at that time he was in another place.

Secondly, the rhetor first puts forward a position or thesis, and then looks for premises that confirm it. The most difficult and, apparently, interesting questions not only of rhetoric, but also of philosophy: where do we get premises to substantiate the positions that we put forward? what parcels and why do we prefer? how and in what words do we formulate them?

Argument reduction is the operation of reducing a position to one or more certain judgments (premises) connected in a certain way. At the logical-conceptual level, reduction is included in the schema of the argument. At the verbal level, which is the most significant, reduction is a set of linguistic means that ensure that the audience understands and interprets the argument in accordance with the rhetor's intention. The composition of the reduction includes a verbal series and an introduction to the argument (convention).

Through the verbal series, the sender of the statement creates a chain of words or phrases that connect the terms of the position with the terms of the premises, creates a verbal image of the subject of thought and a modality in which the statement is evaluated, which achieves the lexical-syntactic unity of the argument.

The words in example (1) are selected and interconnected in such a way as to create a single semantic image of the subject and give the thought a special persuasiveness.

Firstly, the meanings of some words (life, lives, mind) in the context of a phrase are not logical, but lexical - they are included in the meanings of others (true) reduction - the operation of bringing the meanings of the words contained in the position to the meanings of the words contained in the premises.

Secondly, in example (1), the syntactic structure and articulation of the phrase itself is formed by combining several figures of speech. The position contains the figure of dialogism (question-answer), connected with the figure of the environment (it is possible ... it is possible), the repetition of a word or form in various meanings, which introduces the figure of plot (distinction) meanings: "can" in the meaning of "possible" and "can" in the meaning of "in a state" - (meaning: if knowledge is possible, then we are able to know), and after it the figure of gradation, that is, an increase in the intensity of the meaning (lives and does not want to recognize itself as deprived of life).

Thirdly, all these figures create an image of dialogic relations: the question is asked, as it were, on behalf of the audience, and the answer is given in an emphatically impersonal form, as if from the norm of thinking (must think); further, the modal introductory words seem to and of course clearly belong to the speaker, which refers to the listener's assessment and agreement. In such a structure of the phrase, images of "society", "audience" and "speaker" appear, which, in accordance, reveal the truth of the reasoning, which creates the convincing pathos of the phrase.

Fourth, in order to understand the content and meaning of a particular argument, the semantics of the keywords of the lexical chain from the position (inference) to the larger premise is extremely important. Indeed, what does "truth" mean in the context of this speech of St. Philaret? "Truth" and "life" here address the recipient not only to the usual meaning of this word, but also to the gospel context: "And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth; and we beheld His glory, as of the Only Begotten from the Father" [Jn. 1.14]. The word "truth" means not only the correspondence of the statement to reality: the expression "to find the truth" means, first of all, "to find the Truth as such", that is, God, and secondly - "to find any scientific, philosophical, legal, etc. truth, since it is a particular expression of absolute truth." This philosophical and theological ambiguity of the word in the context refers to a certain instance, the natural mind of a person, which in turn is approved by the context of Holy Scripture [Rom 1. 20-24]. Thus, the substantiating premise in example (1) is addressed to the natural mind of a person and to the Holy Scriptures as an instance confirming its acceptability, and not only to the fact of the logical paradox of a liar, which follows from the proposition "Truth cannot be found."

The introduction to the argument, or its conventional component as part of the reduction, is a metalinguistic construction that is needed to evaluate the argument itself or to formulate the conditions for its acceptability. An introduction to the argument is provided in examples (3), (4), (5), where the conditions for the admissibility of justification are established and justified, in particular, the evidentiary significance of premises. So, in example (3), the lawyer argues that the controversy refers to the status of establishing and it is about the presence or absence of the fact of setting fire to the pantry, and not about the qualification of the act of the accused, and this provision is specially substantiated and subsequently repeated. The examples also contain repeated evaluations of the arguments presented ("Hence one possible conclusion<…>. This conclusion is clear as God's day"). In example (5), the introductory part of the argument is expressed even more clearly and appears as a sequence of questions and answers: The unknown is prompted to accept the convention after the Confessor explains the logical technique of substantiation (reduction to absurdity).

So, the arguments of the argument are connected with the position and among themselves through the scheme - the construction of the inference, the conclusion of which (the judgment contained in the position) follows from the premises - the judgments underlying the arguments; verbal series - words, lexico-semantic and syntactic links that define the meaning of the statement; the top that is contained in the base of the argument. The verbal series of an argument is always individual, its structure is determined by the style and target setting of the utterance. The scheme of the argument is individual, but is built according to the rules of logic. The top of an argument, by definition, is a generally accepted proposition. Therefore, it is obviously possible to construct a typology of verbal series of arguments.

The classification of rhetorical arguments gives a picture of the so-called "argumentation field": it allows you to present and evaluate the possible ways of substantiating a thought and to establish which speech-thinking techniques and in what proportion are used in a particular verbal culture. Rhetorical argumentation can be built in various ways and on various grounds. But considering the types of rhetorical arguments, that is, presenting a picture of public argumentation, it should be borne in mind that the position that is put forward by the rhetorician is not necessarily considered as true or false. Moreover, the very truth of the put forward position, even if it can in principle be true or false, is often relegated to the background if a decision is made or an assessment of the subject of speech is given. Therefore, the statements of one class of arguments, for example, arguments to authority, can be considered as true or false, as constructive or non-constructive, as ethically or practically acceptable or unacceptable: an authoritative source may say that the Earth revolves around the Sun, that this should be done in such and such a way, but all this will equally be an argument to authority.

In real rhetorical argumentation, the construction of a verbal series is of decisive importance: the audience of oratory, homiletics, journalism, mass media and even philosophical prose is by no means always able to restore and even more so analyze the scheme of the argument, to identify the source of its premises - words are convincing. Therefore, rhetoric was and remains a philological, and not a psychological or philosophical discipline. But it also follows from this that modern development rhetorical prose urgently requires philological rhetorical criticism, the task of which is to explain the actual structure of public argumentation.

Dialectical Problems and Argumentation Statuses

The rhetorical-dialectical tradition classifies arguments on a substantive basis. Aristotle points out that "there are three types of propositions and problems, namely: some propositions concerning morality, others - nature, and others - built on reasoning. Concerning morality - such as, for example, whether parents or laws should be obeyed more if they do not agree with each other. Built on reasoning - such as, for example, whether the same science studies opposites or not, and concerning nature - such as, for example, whether the world is eternal or not ". This classification of Aristotle systematizes arguments according to the content of dialectical problems. Aristotle connects tops as trains of thought with schemes of arguments, but this connection is one-sided, since the top in its logical part, as a relation of categories, is connected with the scheme, and in its content part - with the verbal series of the argument.

Quintilian's Institutio oratoria develops the ideas of Aristotle and later Greek authors in a coherent theory of argumentation statuses. By speech (oratio) Quintilian understands oral or written statement, which "consists of what is denoted and of what denotes, that is, of things and words" . The word "thing" (res) in Latin has many meanings. With regard to rhetorical terminology, this word can be conveyed as a matter under consideration or an object of thought with its content and circumstances. The most important relation of thought to the word is certainty and accuracy. Any speech denoting a certain "thing" appears as an answer to a question and is given by the content and structure of the question, which, therefore, underlies it.

In relation to the criterion of correctness, questions are divided into "written" and "unwritten" (esse questiones aut in scripto, aut in non scripto), written questions are rational, or questions about things-questions are legal, and unwritten (in rebus) and about words (in verbis). The correctness of answers to legal questions is determined by the relation of the act to the norm. The correctness of answers to rational questions is determined by the relation of facts to words: the truth or falsity of statements.

According to the purpose and nature of the answer, the questions are divided into speculative (is the world guided by Providence?) And practical (should one take part in political life?). Speculative questions suggest three kinds of answers: does a thing exist (an sit?), what is it (quid sit?), what is it (quale sit?). Practical questions suggest, according to Quintilian, two types of answer: how to achieve what is being said? how to use it? (quo modo adipiscamur? quo modo utamur?).

In relation to the content, questions are divided into general (non-final - infinitae) and specific (final - finitae). A general question is called a thesis or a proposition (propositio proposition), a particular question is called a hypothesis (subthesis) or a deed (causa). IN general issues persons, time, place, circumstances are not indicated (should I get married?); private questions contain a designation of a person, place, time, therefore they are reduced to facts and people (should Cato marry?). Any particular question necessarily reduces to a general one: in order to decide whether Cato should marry, it is necessary to determine whether to marry at all. But it is important to keep in mind, Quintilian warns, that there are private matters hidden under the guise of general ones (should one take part in civil affairs under tyranny?). It is also obvious that practical questions should be reduced to speculative ones.

Indeed, considering the most important part of the theory of question-answer, the doctrine of statuses, Quintilian does not associate statuses exclusively with private questions of a practical nature. Statuses are independent of the semantics of variables - the meanings of words, but are determined by the ratio of the meaning of the interrogative word to "the totality of answers allowed by this question": any of the above topics of Roman rhetoric is correlated with any status.

If we consider the logical order of statuses on speculative matters, then the status of establishment (status coniecturalis) will be the first, followed by the status of determination (status finitionis) and the status of evaluation (status qualitatis).

The status of the establishment involves the question of the presence and composition of the fact under discussion. Here the possibility and presence of an act are considered according to circumstantial tops: quality, quantity, place, time, action, suffering, possession, mode of action, as well as person, attitude, order, etc.: arbitrariness or chance, cause, confluence of incidental circumstances. When discussing these issues, "the mind is directed to the truth", which appears as a reality, and the task of the rhetor is to achieve the correspondence of words to things so that the speech becomes true.

The definition status consists in finding the relationship of an individual fact (case) to a species, rule or norm. Here we discuss the question of what this fact is, and how the general views to which it can be attributed. In the status of a definition, Quintilian identifies five main problems: written and conceivable laws, contradiction of laws, norms deduced speculatively, ambiguous norms, and retracted norms. Consequently, in the status of a definition, speech becomes correct from the point of view of a social norm.

The third status - assessments - consists in the relation of the rule and the fact to the special circumstances of the case or problem: the individuality of the actor and the characteristics of the situation, the motives and specific consequences of the action are assessed. Therefore, in the status of evaluation, speech becomes fair, humane and practical, that is, it is associated with action.

In matters of proper legal, Quintilian gives a different order of statuses: establishing, evaluating, determining, recusing (status praescriptionis), in the latter the question of the competence of the court, the competence or legality of the accusation is decided.

“We see,” notes M. L. Gasparov, “that in the transition from status to status, the field of vision gradually expands: with the status of establishment, only an act is in the field of view; with the status of a definition, an act and a law; with an assessment status, an act, a law and other laws; with a challenge status, an act, a law, other laws and an accuser. specific case, in the second - on the understanding of this norm, in the third - on the comparative force of this norm, in the fourth - again on the applicability of the norm. In the field of philosophy, the first statement takes us (in modern terms) to the field of ontology, the second - to the field of epistemology, the third - to the field of axiology. Such a sequence of consideration is applicable not only to such specific issues with which the court has to deal, but also to any of the most abstract.